More than half of Mass COVID-19 deaths have been in long-term care facilities. Examining a system that can’t keep elderly residents safe.

Why did Massachusetts’s nursing homes fail so profoundly? And how can we prevent this from happening again?

A SPECIAL REPORT BY NICOLE ASCHOFF AND PANKAJ MEHTA

A fog of uncertainty surrounds the SARS-CoV-2 virus that has wreaked havoc on families and communities worldwide over the past six months. No scientific consensus has been reached on the epidemiological characteristics of the disease. Scientists disagree on the detailed biological mechanisms underlying coronavirus transmission and acquired immunity. At the same time, public health officials are unsure how to contain the virus, while politicians are at odds over how to mitigate the economic and social fallout the pandemic has left in its wake.

But one thing is certain: The lethality of COVID-19 increases dramatically with age. Nationwide, according to Aug 1 data from the Centers for Disease Control, roughly eight out of 10 people who have succumbed to the virus are over the age of 65, while people under the age of 25 accounted for 0.2% of total COVID-19 deaths.

The picture is similar in Massachusetts, where at the time of this writing, no one under the age of 19 has died of COVID-19. Of the 8,691 COVID-19 deaths reported on Aug 6, 1.7% were adults under 50. Deaths for adults between the ages of 50 and 59, and 60 and 69, were 3.6% and 10.3% respectively. Bay State residents between 70 and 79 accounted for 21.7% of deaths, while those over the age of 80 made up 62.7% of all COVID deaths. The average age of death in total Mass COVID-19 cases was 82 years old.

Even more striking than the age-skewed mortality of the virus is the concentration of its deadly toll. According to the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity, approximately 45% of all US COVID-19 deaths were residents in assisted living facilities and long-term care facilities (LTCFs)—facilities such as nursing homes, rest homes, and skilled nursing facilities that provide residents, who are primarily elderly, with long-term rehabilitative care or skilled nursing care to meet the needs of daily life.

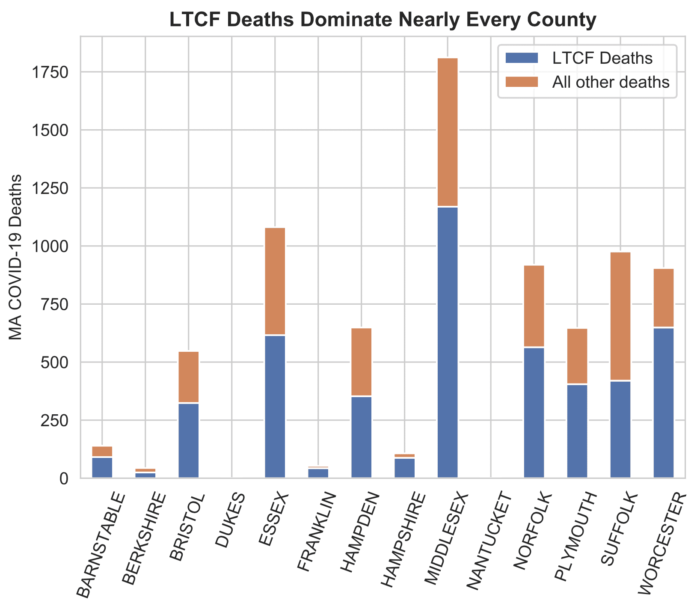

In some states, the concentration was overwhelming. New Hampshire and Minnesota have seen 80% of their COVID-19 deaths happen in LTCFs or assisted living facilities, with 70% in Ohio and 60% in Pennsylvania. In the Commonwealth, more than six out of 10 deaths occurred in LTCFs. Long-term care facility deaths accounted for the majority of COVID-19 deaths in nearly every county in the state.

We analyzed data on COVID-19 deaths at long-term care facilities in Mass over an approximately three-month period ending in mid-June by combining official LTCF death statistics from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health with census data, datasets on health disparities, facility-level data on race and ethnicity, official Medicare provider data, newly collected pricing data, and data on the state’s isolation unit policy. The key findings in our report:

-

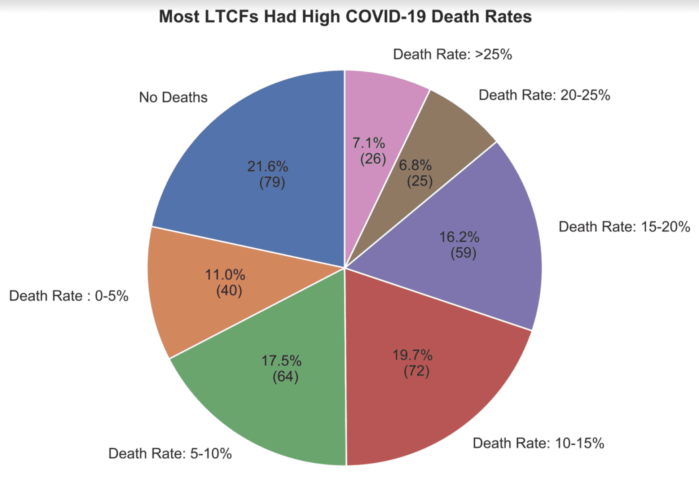

Nursing homes across the state suffered extremely high death rates during the coronavirus pandemic—at least 51 nursing homes in the state saw 20% or more of their residents die from COVID-19.

-

In many nursing homes, COVID-19 deaths were 10, 15, or 20 times greater than the COVID-19 death rate (approximately 1.8%) for all Mass residents aged 80 to 89, as of June 17.

-

LTCFs that created isolation units to care for COVID-19 positive patients from hospitals, acute care centers, and elsewhere in exchange for supplemental payments from MassHealth suffered higher death rates than homes that did not establish isolation units. The isolation unit policy remains in place, making it essential to investigate why these LTCFs had higher death rates.

-

Federal scores for LTCF quality, staffing, and safety assigned prior to the pandemic were inaccurate predictors of resilience. Highly rated homes proved unable to keep their residents safe from the coronavirus, calling into question the validity and usefulness of these scores.

The stark and inescapable conclusion is that the coronavirus pandemic overwhelmed long-term care facilities, revealing a care system unable to keep elderly residents safe.

The battle to quell the pandemic is far from over. Scientists say that the coronavirus, like HIV and influenza, could linger, causing death and disruption until a vaccine is developed or the population reaches herd immunity. Moreover, infectious disease experts say coronaviruses and other infectious diseases with the potential to become pandemics are on the rise globally.

It is essential to understand why nursing homes in Mass were unable to keep their residents safe so that, moving forward, we can develop a plan to protect our state’s most vulnerable residents.

Beyond Holyoke

In the early weeks of the pandemic, public attention was focused mainly on whether or not hospitals would be able to manage a surge of COVID-19 patients. It quickly became apparent, however, that nursing homes were bearing the brunt of the impact as infections and deaths in LTCFs began spiraling out of control.

Mass residents read stories about the Holyoke Soldiers’ Home where at least a hundred veterans would ultimately succumb to the disease, and about the National Guard traversing the state, conducting mobile testing at nursing homes and assisted living facilities. But it wasn’t until May, when the Department of Public Health released comprehensive data on COVID-19 cases and deaths for most LTCFs in the state, that the scale of the tragedy became legible.

The DPH data revealed that Holyoke, while certainly an outlier in terms of both deaths and missteps, was not an aberration. It is joined by dozens of long-term care facilities in which 15, 20, and even 40% of residents died from COVID-19. These death rates are many times higher than the COVID-19 death rate of Mass residents between the ages of 80 and 89 (about 1.8% as of June 17).

Not all areas of the Commonwealth were hit equally hard by the coronavirus. Some counties, such as Middlesex, were hotbeds of infection while others, like Nantucket, Berkshire, and Franklin, were far less impacted. However, within counties, such as Worcester, there is wide variation in death rates between LTCFs, making it essential to examine whether individual characteristics of nursing homes mattered.

Why did Massachusetts’s nursing homes fail so profoundly? And how can we prevent this from happening again? The available data allowed us to pose some important preliminary questions about the coronavirus crisis in Massachusetts LTCFs:

-

Did homes with preexisting health, safety, or staffing problems perform worse when the pandemic struck?

-

Were homes that were pricier or run as nonprofits better able to keep their residents safe?

-

Did homes with more residents of color, or which were located in neighborhoods with more people of color, fare worse?

-

Did bigger homes, or homes in crowded neighborhoods, suffer more than smaller homes in less concentrated areas?

-

Did the EOHHS’s initiative to use LTCFs as locations to care for COVID-19 positive patients brought from elsewhere have a negative impact on the residents of those homes?

These are difficult questions to answer and there is no single best way to attack the problem, but the quantitative data available offers a good start in that it provides important clues as to whether and how the characteristics of nursing homes themselves contributed to the catastrophic failure of care.

Isolation incidents

Given the likelihood that the coronavirus will continue to pose a risk for Mass nursing home residents, it is important to examine the efforts taken to manage the pandemic between March and June. One policy in particular—the Executive Office of Health and Human Services’s ongoing program of paying nursing homes to set up isolation units in which to care for COVID-19 patients—requires more investigation.

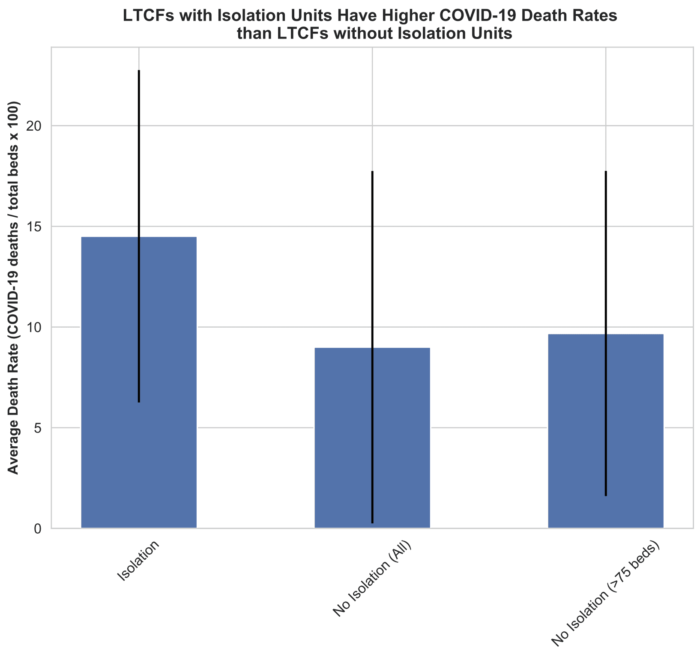

In late March, the governor’s office announced a plan to pay LTCFs to create “isolation units” to care for COVID-19 patients from both within their own facilities and, it appears, from other facilities such as hospitals and doctor’s offices. The nursing homes that signed up for the program, and met the state’s requirements, received a 15% MassHealth rate increase on all MassHealth residents living in the facility—about $30 per MassHealth resident per day.

By early June, nearly 100 LTCFs in the Commonwealth were listed as having dedicated isolation units, able to take patients from “a hospital, the community, or other setting.” As of Aug 5, this program was ongoing, with nursing homes across the state still open to receiving COVID-19 positive patients from hospitals and other facilities.

The policy of creating isolation units was strongly opposed by the Massachusetts Advocates for Nursing Home Reform. In a letter to Sen. Pat Jehlen and Rep. Ruth Balser, both chairs of the Joint Committee on Elder Affairs, MANHR called for an end to the policy, fearing that it would impose unnecessary risks on nursing home residents and lead to increased deaths from COVID-19.

It looks like MANHR’s concerns were warranted. Our analysis shows that LTCFs that participated in the isolation unit program had higher death rates than nonparticipating homes. Even taking into account the fact that most of the homes that participated were larger homes (which did worse overall during the pandemic), the difference in outcomes persist.

A more detailed breakdown of death rates for the two groups shows that homes with isolation units were less likely to have no deaths or low deaths and more likely to have death rates five to 10 and 10 to 15 times greater than the COVID-19 death rate for Mass residents aged 80 to 89.

This is not an explanation for what happened at nursing homes with isolation units, nor is it certain that isolation units were the cause of higher deaths at these facilities. It’s possible, for example, that the higher COVID-19 death rates at these LTCFs were an artifact of COVID-19-positive patients who were brought in from elsewhere dying in the nursing home isolation units, thus increasing the overall death rates of those nursing homes.

Nonetheless, the correlation is deeply troubling, especially given the fact that as of August the program is ongoing.

Protection

The uncertainty surrounding the EOHHS isolation unit policy highlights the importance of getting more detailed information about the response of both nursing home managers and state officials in managing the coronavirus pandemic so we can begin to assess which policy measures worked and didn’t work in the effort to quell the coronavirus.

What clearly didn’t work was federal efforts to mitigate the acute shortage of personal protective equipment for medical personnel. Early in the pandemic, hospitals and nursing homes faced a shortage of PPE such as face masks and gowns to protect staff and patients from contracting and spreading the virus. Global supply chains, which supply most of the PPE used in the United States, broke down, and the federal government failed to alleviate shortages by compelling domestic manufacturing firms to produce PPE. Late in the surge, nursing homes received boxes of PPE from the federal government, but numerous reports indicated that the supplies were inadequate or inappropriate for the specific needs of nursing homes.

The Mass Department of Public Health, along with the Massachusetts Emergency Management Agency, also provided PPE to institutions across the state, but it remains unclear how much PPE individual LTCFs received and whether it was sufficient to meet their needs during the surge of infections and deaths between March and June.

Detailed information on PPE distribution and scarcity, both during the surge and currently, is essential to understanding how and whether a lack of PPE shaped the catastrophic death rates in Mass LTCFs. It is entirely possible that homes with sufficient supplies of PPE were much better able to keep their residents safe and that PPE shortages were a major factor in high death rates.

There is also abundant anecdotal evidence, gathered primarily by local journalists, that a lack of PPE was an important factor in the high death rates experienced by LTCFs in the Commonwealth. Cambridge Rehabilitation and Care Center, which saw one in four of its residents (at least) die from COVID-19, is just one example of a home that experienced critical PPE shortages at the height of the surge. It had a notice posted on its website for weeks requesting donations of PPE from the Cambridge community. Moreover, nursing home workers at facilities around the state reported on numerous occasions that they were asked to do their job with insufficient PPE, putting their own lives, the lives of their family members, and the lives of their elderly charges in severe danger.

Staff inflection

Nursing home access to PPE was almost certainly a factor in many nursing home deaths in the Commonwealth, but what about other facility characteristics? For starters, did the quality of individual nursing homes prior to the coronavirus pandemic play an important role in determining COVID-19 death rates?

Every year, Medicare scores long-term care facilities across the country on a variety of metrics, such as quality, staffing, an annual health inspection audit, and overall performance. We used this data to gauge whether nursing homes that were better rated prior to the pandemic did a better job of keeping their residents safe during the outbreak.

Surprisingly, many homes that had high overall scores prior to the pandemic also had very high COVID-19 death rates. Both “good” and “bad” performers before the outbreak experienced a wide range of COVID-19 death rates. This holds true even considering more detailed scores, such as each facility’s individual “quality” score (derived from a set of quality measures such as the percentage of residents who had experienced pressure ulcers, urinary tract infections, or falls) and its “survey rating” score (calculated from the results of the annual health inspection audit).

We saw similar results when we examined whether nursing homes that had been fined for violations—another indicator of low quality—had higher COVID-19 death rates. Even homes that had received zero fines between 2017 and 2019 had death rates that exceeded 20, 30, and even 40% of their residents over a three-month period.

Were understaffed homes more likely to experience worse outcomes?

Some experts have argued that staffing was a significant factor in how LTCFs fared during the pandemic. Charlene Harrington, professor emeritus of social and behavioral sciences at the University of California, San Francisco, recently published an article in Policy, Politics, and Nursing Practice that found that California nursing homes with low registered nurse and total staffing levels prior to the pandemic had worse outcomes: “Nursing homes with COVID-19 residents were significantly associated with lower CMS nurse staffing and RN ratings than nursing homes without COVID-19 residents.”

Examining nursing home death rates in Mass, however, we don’t see a strong indication that LTCFs with better staffing scores prior to the outbreak achieved lower death rates. Nor does a definitive picture emerge if we use Medicare’s more fine-tuned measure of “RN staffing rating,” which measures whether elderly residents, given their individualized needs, have an adequate number of registered nurses caring for them.

To be clear, this does not mean that staffing, and more specifically, adequate registered nursing staff, is unimportant or was not a critical factor in the high death rates experienced by Mass LTCFs during the coronavirus pandemic. Experts strongly agree that understaffing has a direct and negative impact on infection control and resident quality of life. They also argue that nursing homes are perpetually understaffed, suffer from high turnover due to abysmally low wages for certified nursing assistants, and that federal staffing requirements are insufficient to meet the day-to-day needs of nursing home residents.

This analysis relies on data published prior to the outbreak. Homes that already struggled to meet their staffing needs saw a collapse in their staffing capacity—40% by some estimates—as the pandemic raged. As Arlene Germain, Policy Director for Massachusetts Advocates for Nursing Home Reform, noted in a phone interview, “Staffing dropped dramatically as workers who needed to care for children, who became ill themselves, or were afraid of contracting the virus because few LTCFs had adequate supplies of personal protective equipment, stayed home.”

Many nursing homes cope with high turnover by hiring temporary workers from staffing agencies. This practice has been criticized because temporary workers are often less invested in their elderly patients and are unfamiliar with residents’ individual care needs. But during the pandemic the reliance on temporary staff may have proven deadly. Temporary staff, working in more than one facility, may pose a significant transmission risk. This risk is compounded by an acute shortage of PPE, potentially creating a situation in which the very people hired to care for elderly residents are the ones making them sick.

Medicare data for staffing, as well as for quality and safety, is a profoundly inadequate measure of resilience; even homes that got gold stars were unprepared to handle the pandemic. Clearly, more detailed data on the staffing situation at Mass nursing homes during the coronavirus surge is needed to better understand why LTCFs were unable to keep their residents safe.

Profit or not

There may be other factors that explain the failure of Mass nursing homes—size and neighborhood density, racial makeup, neighborhood poverty. Also, did more expensive, or nonprofit, nursing homes do a better job of keeping their residents safe?

We gathered data from a variety of sources in an attempt to pinpoint the possible reasons why LTCFs in the Commonwealth had such high COVID-19 death rates but came up with few concrete explanations.

Large homes did worse in the sense that, taking the sample as a whole, relatively few LTCFs with more than 100 beds had no deaths. However, some small homes had very high COVID-19 death rates, and medium-sized homes had a mixed performance, with some showing no or few deaths but many others suffering high death rates.

How about nursing homes in more densely populated areas, or poorer neighborhoods? Cities, particularly on the East Coast, were hit far worse by the coronavirus than rural areas, making it more likely that nursing home workers would have been exposed to the virus and brought it into facilities with them. But when we combined the DPH data with Census data and Harvard University’s Health Disparities Geocoding Project data, we saw that neighborhood density and poverty weren’t strong predictors of LTCF death rates.

Another potential factor shaping nursing homes’ death rates in Mass is race. COVID-19 has reportedly had a disproportionate impact on Black and Hispanic Americans, and scholars say this differential impact has also been felt in nursing homes. Using 2011 data (the most recent available) from Brown University’s LTCFocus database, we found that almost no LTCFs with a lower percentage of white residents reported no deaths. Homes with a high percentage of white residents had a wide range of outcomes and many suffered very high death rates.

Professor Tamara Konetzka of the University of Chicago argued in testimony before the Senate that nursing homes in “predominantly nonwhite neighborhoods” are “most at risk.” To see whether this was the case for Mass, we used Harvard’s geocoding data to examine the relationship between LTCF death rates and the racial makeup of the neighborhoods they were located in. Nursing homes in zip codes with 13% or less nonwhite residents had no death rates above roughly 25%, while 11 LTCFs located in zip codes with higher percentages of nonwhite residents saw death rates above 30%. Again, however, the stronger trend is one of a wide range of outcomes in neighborhoods and cities across the state, regardless of their number of nonwhite residents.

Finally, we examined whether the type of nursing home mattered. One might imagine that pricier homes, or nonprofit homes, would do a better job of keeping their residents safe, but the monthly cost of a private room didn’t seem to matter much for COVID-19 death rates.

On the other hand, nursing homes’ ownership structure does appear to matter. Keeping in mind that roughly seven out of 10 LTCFs in the sample are for-profit firms, which can make the difference in performance appear more dramatic than it actually is, for-profit firms still performed worse than nonprofits. Relative to their share of the sample, for-profit corporations saw fewer homes with no deaths and more homes with deaths five to 10 times greater than the death rate of Mass residents aged 80 to 89.

The difference in death rates at for-profit and nonprofit homes is not overwhelming, however. For-profit nursing homes did terribly, but so did nonprofits.

The takeaway

With the exception of the red flag of the state’s isolation unit policy and a few weak correlations between facility size, ownership structure, and racial makeup, the facility-level quantitative data painstakingly collected by state and federal agencies prior to the pandemic provides little in the way of clues for why nursing homes in the Commonwealth failed so profoundly between March and June 2020. Indeed, one might be tempted to conclude that nothing could have been done to prevent the tragic wave of nursing homes deaths.

This is the wrong conclusion. The takeaway from our analysis is, first, that all LTCFs in Mass need help devising strategies and procuring necessary resources to prevent another COVID-19, or other infectious disease, surge. The Commonwealth has the resources and know-how to keep its nursing home residents and staff safe if it takes decisive action now.

The second takeaway is the inadequacy of existing tools to measure resilience in the nursing home sector. Quantitative data, collected at great effort and expense, failed to provide an accurate measure of institutional resilience. This is a serious concern. Institutions that were given a clean bill of health and scored as satisfactory or exemplary roundly failed in the face of crisis—a crisis that infectious disease scientists have been predicting for years.

As experts in the field have long argued, both the standards that we hold long-care facilities to, and the data that we rely on to rate and manage them, are inadequate. We don’t have a clear picture of what’s happening inside LTCFs, and without this understanding it is impossible to keep our elderly residents and their caretakers safe.

To prevent the coronavirus tragedy from reoccurring, it is necessary to radically rethink how we measure success and failure in our nursing homes. If we fail to do so we have only ourselves to blame.

A full copy of the report can be found here. BINJ will continue to investigate the nursing home crisis in Massachusetts and will publish a follow-up study examining how we can protect our state’s most vulnerable residents.

Nicole Aschoff is the managing editor of the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. She holds a PhD in sociology from the Johns Hopkins University and is the author of The Smartphone Society: Technology, Power, and Resistance in the New Gilded Age.

Pankaj Mehta is an associate professor of physics and a founding member of the College of Data Science at Boston University. He is also a member of the Boston chapter of Science for the People.

Nicole is a writer, editor, and public sociologist. Nicole is the author of The New Prophets of Capital and The Smartphone Society, and is a staff writer at Jacobin magazine and managing editor at the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. She received her Ph.D. in sociology from Johns Hopkins University and previously taught at Boston University.