Michael Blanding’s new book goes beyond what “scholars have previously realized.” “At the very least it should be explored.”

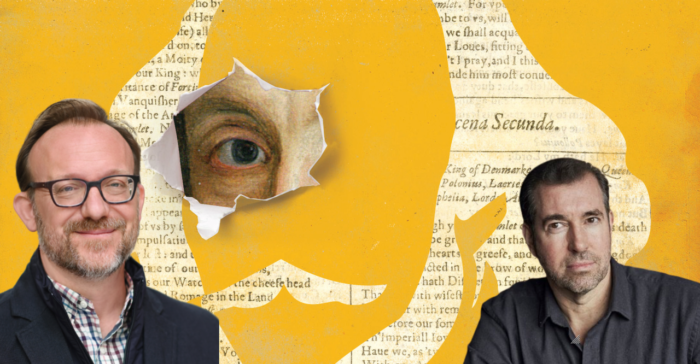

To be convinced that a little-known translator’s writings secretly inspired Shakespeare’s greatest plays, or not to be? That is the question raised by the potential literature-shaking discoveries of a rogue intellectual from New Hampshire and explored by Boston journalist Michael Blanding in his new book, North by Shakespeare.

Using plagiarism-detection software more commonly deployed against Wikipedia-leeching student term papers, “rogue scholar” Dennis McCarthy claims to have found oodles of proof that a lawyer and literary translator named Thomas North authored now-lost plays that Shakespeare adapted into his own world-famous canon. McCarthy says the hundreds of matching words, phrases, and themes between Shakespeare’s plays and North’s surviving works—both published and in private papers—are too close to be coincidence. That still makes Shakespeare a talented writer—but as an adapter of someone else’s work.

Over years of interviews, Blanding went from skeptic of McCarthy’s theories to cautious champion to research partner. In a university library, Blanding made what McCarthy calls one of the most significant finds in the hunt: North’s handwritten notes in one of his own books that suggest even tighter connections to such Shakespearean icons as Macbeth. In an email, Blanding said you don’t need to follow McCarthy as far as he did to find the discoveries fascinating.

“Even if you don’t buy McCarthy’s theory in its entirety, i.e., that Shakespeare was adapting the lost plays of Thomas North,” says Blanding, “I think it’s difficult not to come away with the conclusion that there was some connection between these two writers that goes far beyond what scholars have previously realized—and that at the very least it should be explored.”

Not surprisingly, few scholars are eager to do such exploration. Ever since Shakespeare’s elevation to GOAT status by literary critics of the mid-1800s, a cottage industry of counter-critics has questioned the plays’ authorship, sowing doubt that a country bumpkin from little ol’ Stratford-upon-Avon could pen such complex literature. Shakespeare was a pen name or front for a more famous true author, is the gist of all such arguments. Cranks, crackpots, and conspiracy theorists have hardened many academics. But Shakespearean studies is also, like most academic fields, cozy and territorial, despite being based on slim pillars of surviving evidence—plays weren’t considered worth preserving back then, and we might not have Shakespeare’s today if some of his friends hadn’t printed a posthumous volume as an unusual tribute.

To many academics, a self-taught writer who doesn’t even have a college degree claiming to have discoveries churning out of a computer on the dining room table of his house outside Portsmouth is just another looney or, maybe worse, a threat. Blanding’s book is laced with examples of academics greeting McCarthy with cold shoulders, acidic comments, and even uncredited borrowing of the Northian concept. McCarthy convinced one literature professor, June Schlueter of the small Pennsylvania institution Lafayette College, to partner with him on research, and in an email said he has been treated kindly by some renowned Shakespearean scholars, like Harvard’s Stephen Greenblatt.

“Others have not been so nice, but that is to be expected. From their point of view, I’m an ignorant outsider stirring up others over wild claims,” says McCarthy. “Worse, I’m claiming to have found things that challenge the very ideas to which they have dedicated their lives—ideas they have written books about and taught to others and that have become their source of income and pride. I was expecting to get and understand the rough treatment.”

McCarthy’s theory is so novel and unorthodox that it is unsettling not only to defenders of the Bard, but also to many proponents of alternative authorship. Blanding says that “while Dennis has been rejected by orthodox Shakespeare scholars, he’s also been attacked by Anti-Stratfordians who think someone else wrote the plays. His theories lie in a middle ground with no obvious allies.”

For the majority of us who mostly know Shakespeare from a high school class or a Kenneth Branagh movie, what’s the big deal and who’s right? Luckily for us, Blanding was just as confused at first, with his book leading us on the same exploratory path that took him—and, up to a point, the orthodox Shakespearean world—to a place of buying McCarthy’s method and theory. Formerly a Boston Magazine writer, Blanding is a skilled investigative journalist whose previous books include an expose of the Coca-Cola Company and The Map Thief, another true tale of a New England eccentric. It was on a tour for the latter book that McCarthy approached him and dangled the lure of Shakespearean authorship discovery.

In a 2018 front-page article in the New York Times, Blanding revealed a major discovery by McCarthy: that an unpublished manuscript about historical rebellions, written by one George North, was a previously unknown source for several Shakespeare plays. That find has been embraced and enshrined by the British Library in an exhibit of the “First Folio,” that original printing of Shakespeare’s plays. The trump card Blanding held back was McCarthy’s grander, and far more controversial, theory about Thomas North, a likely relative of George who is named in the manuscript’s dedication.

McCarthy’s use of plagiarism-spotting software to match Shakespeare and the Norths was not a far-out method; other scholars have used it to investigate the Bard’s inspirations. And matches do not mean that Romeo and Juliet would get Shakespeare kicked out of high school for plagiarism. In his day, all playwrights freely rewrote earlier plays (many now lost) and borrowed heavily from books—what we today call “adaptation.”

One of the writers Shakespeare is known to have copied most directly is—you guessed it—Thomas North. North’s translation of Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans by Plutarch, an ancient Greek writer, was a major source for Shakespeare’s plays about ancient Rome, including the classics Julius Caesar and Antony and Cleopatra. Shakespeare took the storylines and entire passages from North’s version of Plutarch. As McCarthy puts it, those Shakespeare plays are closer to North’s Plutarch than the movies Lord of the Rings and The Silence of the Lambs are to their source novels.

McCarthy’s unique claim is that Shakespeare didn’t stop there in borrowing from North. Virtually all of his plays show major inspirations from North’s writings, says McCarthy, including unpublished manuscripts that Shakespeare would be highly unlikely to get his hands on. McCarthy speculates that North wrote a string of now-lost plays that Shakespeare adapted into his own, possibly buying the works from the often financially troubled translator.

The matches that McCarthy claims to have found are rarely cut and paste; it’s about words appearing with similar frequency in similar phrases, the mutual use of rare and unique terms, and similar contexts of theme and plot. Where he sees smoking guns, some may see slightly warm ones, and many academics say nobody’s shooting holes in Shakespeare at all. The plagiarism-software method is part science, part art, and up for debate even though it’s been used by orthodox academics. Blanding says the first professor to use the method on Shakespeare at first praised McCarthy’s method—then blasted him after learning of the alternative-authorship theory.

“That’s part of what I find fascinating about these debates—that even in the use of ‘scientific’ methods, it’s very hard for people to take their own personal biases out of them in interpreting their findings, especially when they’ve invested so much of their time and careers into supporting particular conclusions,” says Blanding. “In fairness, you could say that about McCarthy as well, given how much he has invested in his theories about North!”

But, Blanding adds, McCarthy has other proofs buttressing his arguments, including matches between North’s life and people and places in the plays. North is certainly an engaging figure, with family ties to an infamous murder and a life of diplomacy and military service in an era of civil war and attacks by the Spanish Armada. An entertaining part of the book has Blanding and McCarthy retracing North’s travels across France and Italy while McCarthy’s daughter, Nicole Galovski, films it all for a possible documentary. (Galovski is co-producer of the short film What Would Sophia Loren Do? which was shortlisted for an Academy Award nomination, though it didn’t make the final cut.)

Earlier this year, McCarthy and Schlueter published North’s 1555 travel journal. McCarthy plainly has come to like North, and while a selling point of his adaptation theory is that it doesn’t dethrone Shakespeare, it’s clear where he finds credit due.

“North was remarkably complex and touched by genius in multiple ways: He was a war-weary soldier-knight with an enormous sense of compassion, a steely-eyed realist with the soul of a Renaissance artist,” says McCarthy. “He had been a frequent guest at the palaces of European royalty, fought and suffered in three wars, had ingested the wisdom of the world, and felt everything deeply. He was stirred by beauty, moved by suffering, outraged by evil.”

Of course, as Hamlet once said, the play’s the thing. We’re still reading, performing and watching these plays over 400 years later. In all those hours of dissecting them, does McCarthy still enjoy them as a whole, and what difference do sources and authors make?

“I have developed a much greater appreciation for all of them, but unfortunately, my answer is going to have to be boring: Yes, Hamlet is my favorite play, followed closely by the other three major tragedies (King Lear, Othello, Macbeth),” says McCarthy.

“These are truly mind-boggling intellectual achievements,” he adds, “and they are made even more remarkable once we discover why North originally wrote them.”

NORTH BY SHAKESPEARE: A ROGUE SCHOLAR’S QUEST FOR THE TRUTH BEHIND THE BARD’S WORK. MICHAEL BLANDING. HACHETTE BOOKS.

John Ruch is managing editor of the Reporter Newspapers in Atlanta, Georgia, and former editor of the Jamaica Plain Gazette. His freelance writing recently has appeared in such publications as the Washington Post and the Seattle Times. In what remains of his spare time, he writes fantasy novels.