“When people are using them, they’re not doing it where people can see it, and they’re doing it in a place where they definitely can’t die.”

There were 551 opioid-related overdose deaths across Massachusetts in the first three months of this year, according to the Department of Public Health.

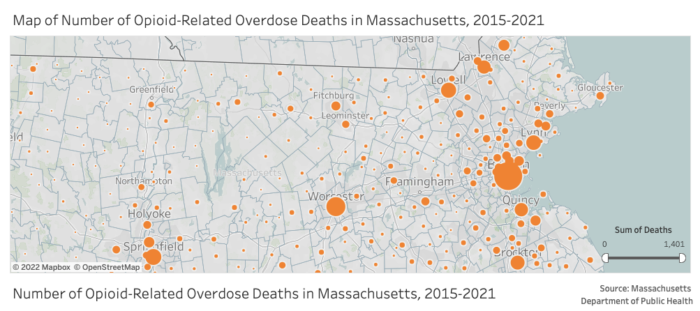

More than 14,000 confirmed opioid overdose deaths have occurred in the commonwealth since 2015. Among 352 cities, Boston, Worcester, Springfield, New Bedford, and Fall River have the most deaths caused by opioid-related overdoses.

As a result of this struggle, there are several harm reduction services, in Boston and elsewhere. As one example, the syringe-exchange program AHOPE provides people with clean needles and places to dispose of those needles in a safe way. However, these heavily impacted cities still don’t have supervised consumption sites where people can take illicit substances under medical supervision in a secure environment.

“You walk down Mass and Cass and you see people injecting substances because they’re literally not allowed inside anywhere else,” said Eva Tian, the director of housing and homelessness for the United Way of Massachusetts Bay and Merrimack Valley.

Tian said having a safe injection site for people who use drugs is a short-term investment that later benefits everyone.

“As soon as they enter those overdose prevention sites, people go in to not die,” Tian said. “When people are using them, they’re not doing it where people can see it, and they’re doing it in a place where they definitely can’t die. They end up actually connecting to resources that help them reduce their substance use and reduce the harms in their lives.”

In Somerville, a city where fewer than 20 overdose deaths occur annually, officials nevertheless recognized that establishing a supervised consumption site is an effective public health strategy. According to a 2021 Needs and Feasibility Final Report by researchers at Brown University, 94% of participants who use drugs in Somerville said they would use a supervised consumption site. Also noted in the study: there have been no reports of fatal overdoses in sanctioned sites worldwide.

“It’s real people connecting with people. You’re not just a data point on a piece of paper,” Somerville Mayor Katjana Ballantyne said in an interview. “It is simply another healthcare service that we know will save lives, provide dignity and provide safety to some of our most vulnerable people.”

Alexandra Collins, an assistant professor in the Department of Epidemiology at Brown University and a leading author of the aforementioned report, said supervised consumption sites are stigmatized because people have stereotypes of substance use.

“We in the United States continue to take a criminalization approach to substance use and that is a key driver of how people view folks who use drugs and view substance use,” said Alexandra Collins, an assistant professor in the Department of Epidemiology at Brown University and a leading author of the aforementioned report. “We continue to put people in prison and continue to criminalize people.”

Collins added other stigmas around the sites are due to a lack of understanding of what they do and if they reduce overdoses, and said establishing such facilities faces legal difficulties on the federal level.

During the Trump administration, in Jan. 2021 an appellate court ruled against a plan to open a safe consumption facility in Philadelphia, arguing it would violate a drug law from the 1980s that bans running a place where illegal drugs are consumed. However, the Supreme Court declined to hear the case in October, and in February the Department of Justice signaled to the public that they were “evaluating” such facilities and talking to regulators about “appropriate guardrails.”

“We need massive policy reform that makes it easier to access substance use treatment that makes it easier to roll out innovative harm reduction strategies and evidence-based interventions to address the overdose crisis,” Collins said. “If these sites are not legal to operate or to implement, it can be probably the biggest hurdle first for places.”

At the state level, officials including outgoing Mass Gov. Charlie Baker opposed the concept of supervised injection sites in 2018, with the governor claiming they are “not a responsible instrument to tackle the opioid crisis.”

However, Ballantyne said Somerville officials are hoping to work with the next governor.

“I can just say that I disagree with Governor Baker’s stand,” the mayor said. “Our neighbors are dying. I’m looking forward to working with the next governor to take a fresh forward-looking approach to this really important public health innovation.”

Somerville has been working with Brown University and Fenway Health over the past two years to research the necessity and feasibility plus design options and research locations for a supervised consumption site. Matthew Mitchell, the city’s prevention services manager, said the preliminary research helped the community to understand the need for the consumption sites and also revealed myths surrounding substance use disorder.

“I think having open and honest conversations and helping people understand that individuals who use drugs are friends, family members that deserve the same love, support, and attention as anyone else in any type of other medical related disease or condition,” Mitchell said.

Davis Square is a gathering place for unhoused people. The public can see discarded needles, Ballantyne said. She recently spoke with a father who told her he doesn’t want his two children to see needles in the square.

“If there’s an option for them to be someplace safe, then most likely the needle reductions will go down,” Ballantyne said. “And these people will not be doing it in public in front of your five-year-old daughter.”

Ballantyne noted the city has been launching community engagement efforts such as having these one-on-one conversations with residents who have not supported the concept of supervised consumption sites. They’ve also held community meetings and posted on social media about the concept.

Meanwhile, an 81-page report prepared by Fenway Health in July recommended the city begin with a “fixed modular unit” in a city-owned parking lot. For Somerville, the next step is to integrate a public procurement process.

“The next piece is to figure out how to select those locations in conjunction with a community process and determine the program,” Ballantyne said. “The timelines for modular units are a little bit longer right now but we’re trying to do as much research and everything upfront so we can execute as quickly as possible.”

Mitchell said that a supervised consumption site has to be a site that is open and driven by participants.

“It needs to be designed by individuals or at least informed by individuals who use drugs,” he said. “It’s so important to listen in and to understand why there’s so much passion around a topic like a supervised consumption site because people are dying.”

This article is syndicated by the MassWire news service of the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. If you want to see more reporting like this, make a contribution at givetobinj.org.

Cici Yu is a junior studying journalism and public policy at Boston University. She is interested in city news, specifically about public policy, public health, and education.