A seemingly endless recitation of events

This book, the last in a tetralogy depicting American politics and the rise of the conservative political movement between the early 1960s and Ronald Reagan’s 1980 election to the presidency, raises one central question in the mind of the reader: How much is too much? Too much detail, too many pages? That’s not a question this review can answer definitively. But for what Reaganland offers in insight, it asks too much in terms of patience from its readers.

Each volume in Perlstein’s series is significantly longer and more ornately detailed than the last. The series began in 2002 with the publication of Before the Storm, which told the story of the rise and fall of Barry Goldwater’s presidential ambitions in a relatively economical 516 pages. Eighteen years later, the reader crosses the finish line of Reaganland at the 914 page mark.

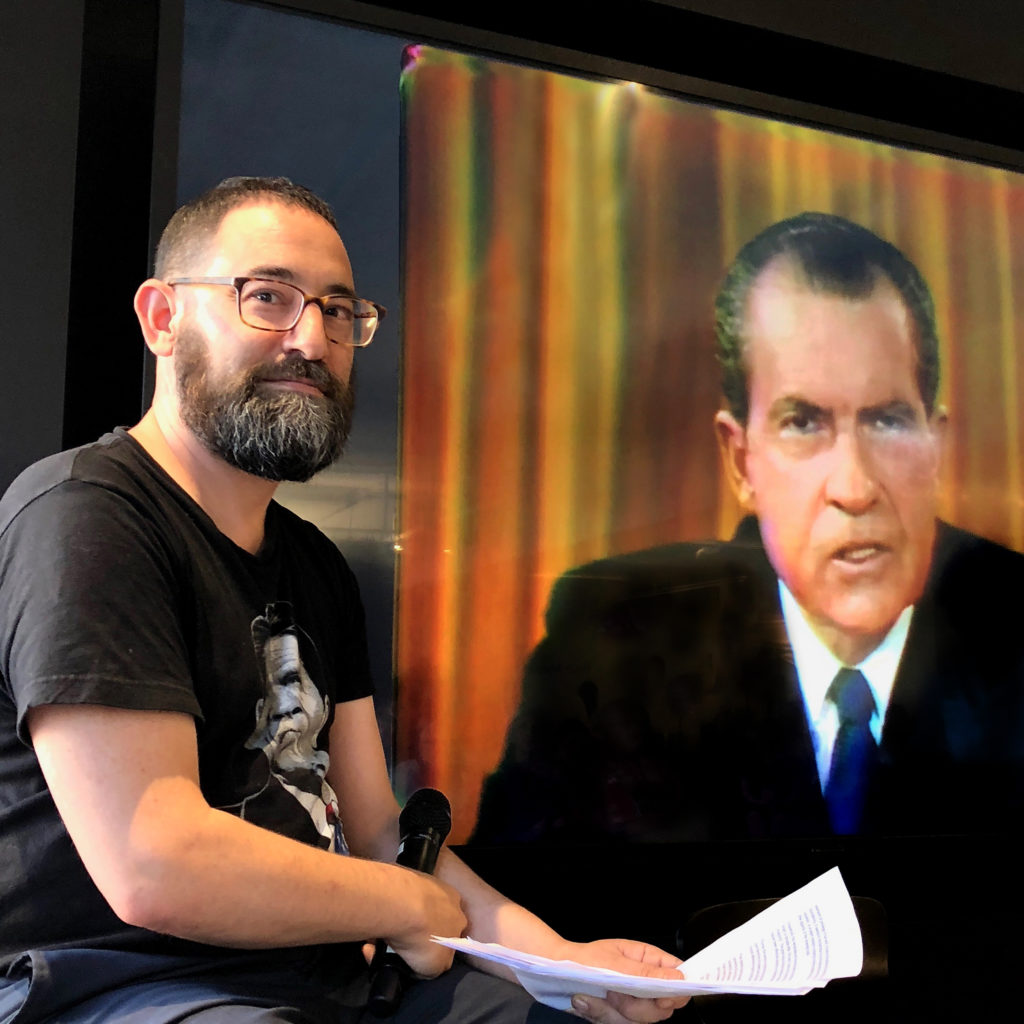

The series took a conceptual leap with the second volume, Nixonland, published in 2008. Perlstein had already shown an interest in depicting a panoramic view of the times surrounding his subject when writing about the Goldwater campaign. In Nixonland, this turned into an attempt to chronicle the history of the nation as a whole during the long duration of a given campaign season, broadly construed. The book was a big hit, a bestseller and in a small way part of the Obama ‘08 gestalt, at least from where this reviewer, who eagerly awaited and read the volume, stood.

Perlstein relied on an impressively wide array of period newspapers to construct both his pictures of electoral campaigns and of a “national mood” in Nixonland and its successor, The Invisible Bridge, published in 2014. He even encouraged readers to “build their own Nixonland” by including links to his sources through newspaper search engines. While mostly a light-hearted encouragement for readers to delve into primary sources themselves, the sort of thing any history teacher is glad to see, it points to a serious aspect of Perlstein’s historical method. Increasingly often, Perlstein presents findings from his archive — most often newspaper sources — to the reader with little in the way of analysis or comment. Much of the time, these archival blurts are presented in a chain, a cluster of chronologically-proximate happenings that, taken together, are presumably meant to invoke a gestalt.

This is a tried and true method for getting across the feel of a given time and/or place, and Perlstein is not shy of his indebtedness to the “gonzo” journalists from the era he covers for it. Even when not making an explicit argument, it’s clear that by choosing what goes into the clipping-gestalts, an author is making an implicit statement, trying to summon a particular image and mood. Rick Perlstein is not a man who lacks for opinions about the past. In The Invisible Bridge in particular, he used these illustrative sections as something like instrumental breakdowns on an album, getting across the feel of a country in the midst of a collective nervous breakdown in the mid-1970s.

The method gets away from Perlstein in Reaganland. The bulk of the book is made up of a seemingly-endless recitation of events, in Jimmy Carter’s White House, on the long 1980 campaign trail, in the country at large, and internationally, especially in Iran. Perlstein’s analysis of these events is limited to introductory paragraphs to selected chapters and brief — sometimes one word — asides to the reader interspersed throughout. Readers are meant to divine the gist of the book through reading many, many descriptions of selected events between Carter’s election and Ronald Reagan’s, sometimes loosely organized by theme but often strung together chronologically.

As mentioned above, this reviewer is a long time reader of Perlstein’s, having followed this history series nearly from the beginning and having read many of his journalistic and opinion pieces. From this past knowledge and what I read in Reaganland, the reviewer can discern a few arguments that the book makes. The following is a list of these points, in descending order of how certain the reviewer is Perlstein meant to convey them:

- The late ‘70s were a time of widespread ennui and dissolution of certainties in the United States.

- The conservative movement Perlstein has been charting reached an apogee in the years 1976-1980, uniting Christian conservatives, anticommunists, and free marketeers into a single cause.

- Ronald Reagan, while launched into prominence by this movement, was able to gain the Republican nomination and the presidency by being all things to all people and an expert summoner of dreams of a better America- of making America great again.

- The Democratic Party was unable to stop Reagan due to its own internal fractures between the emerging neoliberal wing, represented by Carter, and a left wing itself divided between the party’s New Deal past and a theoretical democratic socialist future, led by the appropriately ambivalent Ted Kennedy.

These are all valid, if not exactly mind-blowing, analyses of the period in question. But they are drowned in hundreds of pages of detail about what was going on in America and its newspapers at the time. Much of this notionally serves to evoke atmosphere and mood, like Perlstein’s dwelling on miserable national failures such as the Love Canal spill, the New York City blackouts, or the spate of highly public serial murders the period saw. A lot of the rest of it is meant to create a granular portrait of the long campaign season leading to the 1980 election, including extensive biographical sections on figures like John Connally. Between them, they entail hundreds of pages of narrative and description in an effort to summon mood around a set of arguments that could be dispensed with in a book a quarter of the bulk of Reaganland, or in a long magazine article, for that matter. This imbalance between description and analysis recalls the chronicles written by scribes in the Middle Ages, where relevant-seeming events — often, as in Reaganland, picturesque disasters — are listed, one after another after another. This was supposed to have gone out the window with the work of Edward Gibbon and other historians who used sources to construct an argument about the past, but alas, here we are.

The experience of reading Reaganland is that of drowning in a sea of bullshit. This is made somewhat more interesting by noting that it is not the author’s own bullshit, as is generally the case in such harrowing reading situations. Perlstein’s analysis, elusive though it can be, is not bullshit. Rather, the reader struggles to keep their head above the bullshit Perlstein presents, the bullshit of the campaign trail, the bullshit of political theater and minutiae, the bullshit of cultural ephemera from a time, the late 1970s, famous for producing loads of it, the bullshit, one is tempted to say and wonder if this is what Perlstein was getting at all along, of America, hundreds of pages of it.

The effect is magnified by the awareness that all of the political theater Perlstein lovingly, endlessly details, the horse race, the gaffes, the gotchas, the spoofs, the goofs, turned out never to matter. A minor character in Reaganland, Donald Trump, went on to prove that in the years during which Perlstein was presumably researching and writing this book. Everything that tripped up the likes of John Connally, Howard Baker, Paul Laxalt, Jerry Brown, John Anderson, Ted Kennedy, George H.W. Bush, every other politician squirming like so many bugs under the rock of democracy, and which nearly tripped up Reagan on his way to the presidency, all are things that happened to Trump and did nothing to impede him.

In a way, it’s almost admirable, the way Perlstein refuses to let our Trump-dominated contemporary reality steer him away from creating this all-too-detailed simulacrum of the past. No Trump derangement syndrome for this particular left-liberal, at least not in this, arguably his magnum opus. Maybe this aspect will attract some readers, nostalgic for an era when politics seemed to have rules. For others, it will amplify the frustration of the slog.

Rick Perlstein, Reaganland: America’s Right Turn 1976-1980. Simon and Schuster, 1120 pp, $40.

Country Music Concerts Near Me

How To Watch NBA Live Streaming

Peter Berard is a writer and organizer who lives in Watertown, MA. For more of his work, check out peterberard.substack.com.