“If the city government acquires face surveillance technology, anyone who attends future protests could be tracked and identified, further threatening our right to rally for justice.”

In a time of so much sickness and unrest, the start of Tuesday’s Boston City Council hearing on a proposed “ordinance banning city government use of face surveillance technology” was cordial—even though the police were involved, and even with more than 100 people queuing to testify online, effectively maxing out the Zoom room’s threshold and blocking some councilors from joining.

Despite the wait, agreement filled the screen as things got underway, with councilors voicing concerns about tools that parse and identify people based on movement and looks. Councilor Michelle Wu called it “technology that has been proven to be racially discriminatory,” and said, “We are thankful [the Boston Police Department] agrees with that.” Participating from his office at BPD headquarters, Commissioner William Gross agreed—for the most part.

“The department does not currently have the technology for facial recognition,” Gross said. The commissioner requested an additional session to finesse specifics and address privacy issues, and said his testimony was meant to provide “a background to BPD’s current practices and [to] identify potential technological needs.”

“As technology advances,” he added, “many vendors have and will continue to incorporate automated recognition abilities …” The tech, as Gross explained, does not meet Hub standards at this time. For sure, studies have had damning results, with one American Civil Liberties Union test showing that Amazon’s software mistakenly matched 28 members of Congress to criminal mugshots. Still, Gross left the door open for further discussion in the event that something better and more accurate comes along. Up until now, he said BPD has “prohibited [face recognition] features with the intention of having rich dialogue with the community ahead of any acquisition of any such technologies.” But while that may be true of his brief tenure, it’s historically inaccurate.

It’s promising that Councilor Wu, along with co-filer Councilor Ricardo Arroyo, is focused “on banning city government use of face surveillance technology and a companion ordinance to bring transparency, accountability, and oversight to the City’s use of surveillance technology more broadly, and to protect student privacy.” However, when you’re talking about equipment from the future, the type of eyeball-scanning digital enhancements used in almost every cop movie and television show, it’s important to recall the recent past.

Boston trolling

I was particularly interested in Tuesday’s hearing. In 2014, I was one of three reporters on a team that caught the City of Boston using facial recognition without any community input. It was all done in secret, and officials denied our findings right up to the week we published. The police straight up lied to us, claiming, “BPD was not part of this initiative. We do not and have not used or possess this type of technology.” To the contrary, the documents we had obtained included photos of Boston police using the equipment in question.

Specifically, along with fellow reporters Kenneth Lipp and Jonathan Riley, I helped reveal how in May and September of 2013, during the first two Boston Calling concerts which took place on City Hall Plaza (before promoters relocated the music festival to Allston), outside contractors helped municipal authorities deploy resources designed to analyze body and facial patterns of “every person who approache[d] the door” in order to gauge panic levels and crowd sentiment. That scoop echoed as far as Europe, with the BBC using the footage we found in a segment on the subject, and publications ranging from WBUR to Popular Science amplifying the story. But again, memory is short around here, so I wanted to remind people of a few points.

As documents that our team found and the city confirmed were real showed, in the first few months of 2013, Boston was piloting a new “smart surveillance” program with IBM. Among other bells and whistles, accoutrements included a “People Search” function to label individuals by “baldness,” “head color,” “skin tone,” and clothing texture. On the April morning of that year’s Boston Marathon, which would be fatally bombed by the Tsarnaev brothers, the city’s chief information officer told the trade publication Information Week [in a post that vanished after two explosive devices detonated near the finish line]: “It’s the city’s job to make sure all goes according to plan.”

Though surveillance footage was used in part to identify two suspects in the aftermath of the April 15 bombing, IBM’s smart video analysis bore no fruit in the investigation. But whereas some may have interpreted it a failure of the real-time video tech in trial, IBM saw opportunity. Records secured by the Dig showed that an employee of the company met with city officials on the day after the marathon, and at least two additional times over the following two weeks. After explaining how the city’s incoming surveillance info “currently is not shared,” “often is not recorded or analyzed,” and therefore “is not fully leveraged,” IBM persuaded the city to re-purpose surveillance hardware that was already in place.

At the time of our reporting in 2014, Mayor Marty Walsh had only been in office for eight months, and was able to blame his predecessor Tom Menino for the egregious violation of public trust. A spokesperson for Walsh told the Dig: “The City of Boston did not pursue long-term use of this software or enter into a contract to utilize this software on a permanent basis” due to a lack of “practical value for the City’s public safety needs.”

This time around, the city’s in a similar situation—a comparable arrangement was the reason that so many people attended the Tuesday hearing. As the ACLU told reporters in May about BriefCam, a company the BPD contracts with for surveillance tech, while “Boston’s current version of the network does not include facial surveillance features,” if the community renews its contract and upgrades to the company’s latest software, officials “will have instant access to a dangerous and unregulated surveillance tool.”

“A mere software update at the Boston Police Department could super-charge Boston’s existing network of surveillance cameras, establishing a face surveillance system capable of monitoring every person’s public movements, habits, and associations,” an ACLU spokesperson said.

Pandemics and biometrics

Facial recognition is critically relevant to all protests, especially those raging nationwide over police violence. Matt Allen, a field director for the ACLU of Massachusetts, wrote in an email to the media and advocates ahead of Tuesday’s hearing: “We can’t give the government new tools to oppress ordinary people. … If the city government acquires face surveillance technology, anyone who attends future protests could be tracked and identified, further threatening our right to rally for justice.”

Protest woes aside, when councilors Arroyo and Wu introduced their ordinance in May, it was nearly a month before George Floyd was killed by a Minneapolis cop spurring coast-to-coast protests. Their immediate concern, as outlined in the ordinance, was that: “Governments around the world are responding to the COVID-19 pandemic with an unprecedented use of surveillance tools, including face surveillance technology, despite public health and privacy experts agreeing that public trust is essential to an effective response to the pandemic.”

It’s all so very true and frightening. As the New York Daily News recognized in April: “In the U.S., the controversial facial recognition startup company Clearview AI is said to be talking with state agencies about using its technology to ‘track patients infected by the coronavirus,’ while, “in China, facial recognition software is linked to a phone app that codes ‘people based on their contagion risk’ and determines when they’re cleared to enter an array of public spaces; and, in Russia, facial recognition technology is being deployed to track people who violate quarantine orders.”

During Tuesday’s hearing, Commissioner Gross emphasized, “The department rejects any notion in the ordinance that we are or would ever use any facial recognition technology in our response to the COVID-19 pandemic.” Coronavirus was never the sole concern though. “Studies continue to provide evidence that facial recognition technology disproportionately harms Black and Brown communities which further widens the racial inequities we already face,” Arroyo said in a statement in May.

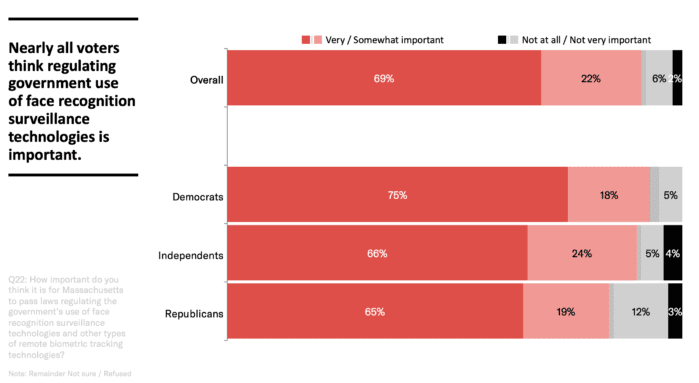

According to an ACLU poll conducted by Beacon Research from last year, when the civil liberties group launched its “Press Pause on Face Surveillance” campaign, “Nine-in-10 (91%) Massachusetts voters think the Commonwealth needs to regulate the government’s ongoing use of face surveillance technology.” To that end, civil liberties advocates are pushing for a statewide kibosh on such newfangled fascist accessories, and last month Massachusetts lawmakers advanced “An Act establishing a moratorium on face recognition and other remote biometric surveillance systems” to the Joint Committee on the Judiciary. This as towns and cities as big as Cambridge and Northampton have delivered similar reforms at the municipal level, however temporary.

Boston’s dealings with IBM on “smart surveillance” appear to have wrapped years ago, presumably soon after our series exposed the relationship. The company, meanwhile, reportedly left the space altogether. In a convincing testimony on Tuesday, MIT Media Lab researcher Joy Buolamwini said, “IBM’s decision to stop selling facial recognition technology underscores its dangers.”

One 2018 study conducted by Buolamwini, who is the founder of the Algorithmic Justice League, showed significant gender and racial biases in AI [artificial intelligence] systems. “In one test I ran,” she said, “Amazon’s AI even failed on the face of Oprah Winfrey, labeling her male. … Personally, I’ve had to resort to wearing a white mask to have my dark skin detected by some of this technology.”

In one of his turns, Gross acknowledged such extensive problems with current AI. At the same time, the commissioner balanced his knocks against face recognition tech with an enduring extolment of cameras for cop work, a position BPD seems to take on all recording that doesn’t involve first-person police body cameras. As for BriefCam, whose contract with BPD expires on Sunday, Gross said he will check up on the deal because he “doesn’t want any technology that has facial recognition.”

The commissioner put on a seriously convincing show, but it didn’t hold up against evidence, or lack thereof. Shining light on such comments, Kade Crockford, director of the ACLU of Massachusetts Technology for Liberty Project, said the BPD has so far refused to provide requested information about the BriefCam contract. Furthermore, while the department may not use face recognition itself, it works with federal agencies like the FBI and ICE, and apparently can share the biometric data those relationships yield.

All of which sounds a lot more like the secretive BPD I know.

This article was produced in collaboration with the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism as part of its Pandemic Democracy Project.

HELP DIGBOSTON WEATHER THIS STORM AND CONTINUE PROVIDING ARTICLES LIKE THIS ONE

A Queens, NY native who came to New England in 2004 to earn his MA in journalism at Boston University, Chris Faraone is the editor and co-publisher of DigBoston and a co-founder of the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. He has published several books including 99 Nights with the 99 Percent, and has written liner notes for hip-hop gods including Cypress Hill, Pete Rock, Nas, and various members of the Wu-Tang Clan.