“If you’re living the life, you don’t need to go see how someone else is interpreting it.”

“I suppose you plan to run the interview after I’m dead.”

That’s what Charles Giuliano emailed me a few months ago about this interview, which I conducted last December. Thankfully he’s not dead, but is instead still cranking out near-daily content on his culture site, berkshirefinearts.com, which he runs from his current home in Western Mass.

Alternative journalists don’t often last for the long haul, and frankly, Giuliano may be the most durable such reporter to date. That’s not why I have sat on our chat for nearly a year—there were just some scheduling issues, then a pandemic—but it’s nonetheless worth noting.

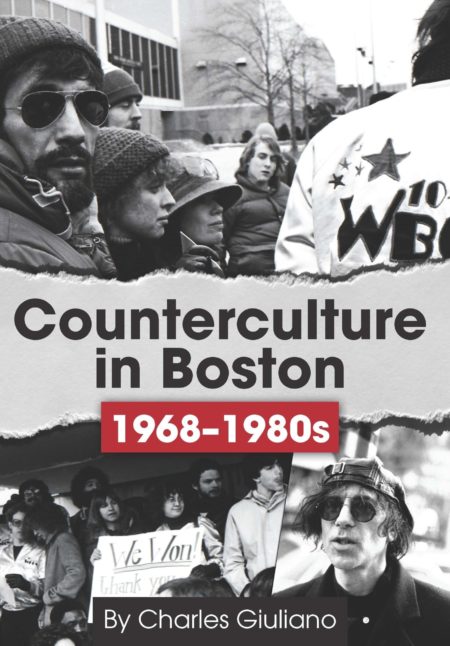

I don’t have heroes or respect elders the way you’re supposed to, but as much as I find inspiration in the journalists who came before me, Giuliano is a king. With the throwback theme in this issue, I felt it was appropriate to finally publish our chat about his days reporting for the Boston Phoenix, Avatar, and the Patriot Ledger, among others. We also spoke about his outstanding 2019 compendium, Counterculture in Boston: 1968-1980s, as well as his thoughts about the 1977 film Between the Lines, in which it has been said that the supporting lead protagonist played by Jeff Goldblum was inspired by none other than a young Giuliano.

What was your timeframe in Boston? From when to when?

I’m a native Bostonian. We were always there; we left when we finally retired, which was 2006.

Where was your first editorship?

Boston After Dark, 1968.

Following a quick discussion about Boston music venues in the 1970s …

At that time, I was writing primarily for the Boston Ledger. It was a weekly paper, the editor was John Van Scoyoc. The Ledger had a very good arts staff. They kind of got me started with photography, because John would give me film. You would shoot it, and you would come in on deadline day, and various people would pass the film in, and the techie would develop it and print a couple of frames and give you back the film. So a lot of what I’m doing now is going back into those archives and tweaking and printing. Of course after that I learned to process my own film, so it became vast. … When I could develop and print my own film, that became an asset working for these smaller newspapers. I can’t remember them all.

There is so much that happened with alternative newspapers in Boston in the 1970s. What is especially important to remember and for people to know about?

The mainstream media wasn’t covering what we thought was important to cover. I entirely owe my career to Arnie Reisman, who was my editor at the Brandeis Justice, and then became editor at Boston After Dark and hired me and all kinds of other people, and also was essential in convincing [Phoenix publisher Stephen] Mindich to expand from being an arts and entertainment paper to branching out and covering the political scene. That’s when the Boston Phoenix and Boston After Dark made an impact, because they were doing all of that reporting that wasn’t happening in other papers. And of course, many people who wrote for them went on to become very distinguished in the field of journalism. Also, the Globe was not stupid. Because of what was going on in the alternative press, the Globe decided to cover jazz and rock music.

This all sounds extremely exciting, a thrill a minute, but did it feel that way at the time?

I was more of a [music] fan than a writer. It was like that. I remember one time when the Kinks and Led Zeppelin were in town at the same time, and this woman who was a groupie wanted to organize the afterparty for Led Zeppelin, and the Kinks crashed it and the Kinks and Led Zeppelin hated each other.

With all that partying and buddying up with artists, how did one develop their [journalistic] compass in that environment?

You’re talking to the wrong person. Professionally I have no morals. At one point, I had just flown out to LA for an Elton John party and there was a lot of crazy stuff going on, and I came back and was just helping out a record company that was trying to launch a band, and I get this call from [a Globe reporter] essentially asking that question—what is the morality of your doing x-y-z? And I told him to go fuck himself and hung up.

What was access to artists like back then?

For me, the big issue was the switch from access to corporate. During the height of the [legendary Boston venue] Tea Party, you could go right up to somebody and have a conversation. It’s hard to say exactly when it happened, but as it became big business, and ticket prices went up and up, then there was limited access. I used to work for a paper called What’s New and the guy I worked with was very good at dealing with these companies. He’d say, Go, and after the show they’ll be waiting for you. You needed someone to run interference. You couldn’t do that on your own. I remember one time I went backstage and walked in and talked to Yes, and they said I was the only interview on the tour because management was so limiting on access.

What were the readers looking for?

I think there’s a generational gap [in this conversation]—a Grand Canyon issue. Your position is such a sea change of difference from what I was doing and what was going on. I don’t consider myself a paradigm or an authority; I was on the scene, I talked to these people, and this is what happened. I’m not the moral compass of my generation; I wanted to get drunk and stoned and laid like everybody else. Those are interesting questions, but it’s not what we were thinking about at the time. … I didn’t know anything. I could go into a dressing room and talk to these guys and ask them questions and write things down in my little book. I was getting educated on the spot.

Some incredibly famous people [to me at least] show up in the pages of your book. [New Yorker cartoonist] David Sipress among countless others …

It’s interesting you mention David Sipress, because he started with Dave Wilson doing cartoons for what became Broadside Free Press. He’s become a very important national cartoonist, but he started with Dave Wilson. … What was interesting about that time was you could show up and start as an intern, and a month later you would be the editor.

Nothing’s changed, man. Nothing’s changed. … Tell me more about Broadside …

Dave Wilson is an incredibly important person in this whole discussion. Dave essentially started Broadside as a tip sheet to tell people what clubs there were, who was playing, listings. And it grew into becoming the foremost vehicle for information about folk music and blues in America, a tremendously important resource. From Dave I know that there was terrible infighting in the folk scene regarding who controlled Club 47, who controlled the Newport Folk Fest, and who was being booked where. There were a lot of people fighting over who was the top man on the totem pole.

What do you think of Between the Lines anyway?

I want to make a point about that, which is I never saw this film [in which] I’m allegedly a character. I guess the [reason] would be several things—arrogance, stupidity, youth, ignorance. And also, if you’re living the life, you don’t need to go see how someone else is interpreting it. You’re too busy doing it. …

My shortcoming over the years has been that I’m too busy to promote myself. At this point, I’m trying to promote this book, and it’s something I should have done 20 or 30 years ago.

A Queens, NY native who came to New England in 2004 to earn his MA in journalism at Boston University, Chris Faraone is the editor and co-publisher of DigBoston and a co-founder of the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. He has published several books including 99 Nights with the 99 Percent, and has written liner notes for hip-hop gods including Cypress Hill, Pete Rock, Nas, and various members of the Wu-Tang Clan.