“I thought my friends would feel uncomfortable by the fact that I had to take care of my mother while they were visiting.”

“I feel like I had to handle ‘grown-up’ matters, even as a preteen, and had to develop the nurturing aspect of my personality earlier than I would have, had my mother not been sick.”

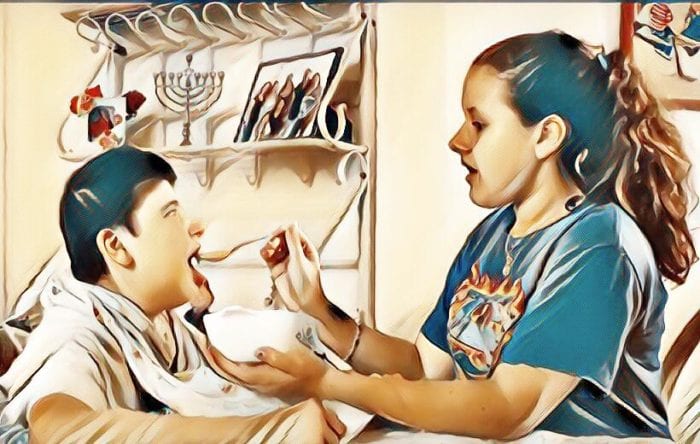

Nadya Rachid, 21, is a Puerto Rican opera singer based in Boston. Her mother has multiple sclerosis, and she can’t recall a time as a child when she was not her mother’s care provider. At age 12, she began cooking for both of them, and helping her mom stretch when she was in pain.

Around the same time, Rachid became self-sufficient. Her responsibilities included fulfilling basic needs, such as helping out with chores, but then also extended to things like driving her mom to appointments. Eventually, her duties became more complex. Rachid’s social life changed during her teenage years, as she became more involved in taking care of her mother.

“My friends stopped coming over,” she says. “I drifted apart … mostly because I thought they would feel uncomfortable by the fact that I had to take care of my mother while they were visiting.”

A 2017 VICE News segment put a rare light on caregiving youth

Children who watch after loved ones often experience trouble in their academic and social development. Such serious responsibilities can lead to social, emotional, and financial issues, all barriers in the learning process. Nationally, around 3.4 to 4.5 million children care for someone, often performing tasks that even adults would consider arduous, sometimes for more than 20 hours a week, including giving medication, changing adult diapers, preparing meals, and adjusting oxygen tanks.

In Florida, the American Association of Caregiving Youth supports children through these struggles. Through various programs, the AACY provides academic, social, and emotional resources to children ages eight to 18 who play a critical role in the life of a relative.

“It really impacted my life.” Connie Siskowski is the founder of AACY and its Caregiving Youth Institute (CYI). Long before that, she was a childcare provider for her grandfather at the age of 12.

“It was at a time when trauma in children wasn’t recognized,” Siskowski says. “That kind of set the stage for me.”

These days, she says the institute “seeks to connect kids with each other [and] to advocate.” If the AACY has one major problem, it’s invisibility. Despite the issue of youth caregiving being obvious and right out in the open, the situation is not formally recognized by most school districts, states, or municipalities. If a high school student tells a teacher that they couldn’t finish an assignment because they had to take their mother to the hospital on the train in the snow, and the teacher isn’t sympathetic, there is rarely a designated resource to turn to. That’s where AACY comes in.

There are many battles on this front, with a lot of them pitted against immigrant families. Afraid of being separated by US Immigration and Customs Enforcement, people are reluctant to communicate with schools about the adult tasks that their kids take on at home.

“No one has looked at the trickle-down effect that passes down to the children if you don’t have health insurance,” Siskowski says. “Or if you have health insurance, but it doesn’t cover homecare, especially on a long-term basis.”

COVID-19 has also presented new obstacles. Most young people are unable to socially distance in their living situations, while the digital divide poses a problem in the Florida counties they work in, and in-person interactions are more difficult if not impossible.

“How can you have friends over when a person in your family is sick?” Siskowski says. “This affects development and social skills.”

AACY has had success in Florida; among other metrics, 98% of the kids in its program graduate high school. Still, it is the only agency in the entire country that is laser-focused on this demographic. In Massachusetts, youth caregiving doesn’t yet exist as a recognized legislative issue. Siskowski says the scarcity of resources is due to a lack of education among lawmakers and community leaders, who often believe that the most viable solution is to place children in foster care.

“That is not … healthy for anyone,” Siskowki says. “Each time a child graduates from high school, their earning potential is $10,000 a year more.”

As for Rachid, the opera singer in Boston … Her relationship with her mother has since changed for the better.

“Back in high school, I remember resenting her even for things that were out of her control, which eventually led to arguments,” Rachid says. “I visit my mother now as her daughter, not her caregiver, and the relationship has certainly blossomed since.”

Maria Jimenez Moya is a Mexican journalist. She obtained her degrees in Journalism and International Relations from Boston University. She is passionate about telling stories of marginalized stories and create advocacy through them. In her free time, you can find her watching the newest Netflix documentary or on the lookout for a new story.