Robinson also passionately advocates direct democracy and popular participation in small scale, but he is oddly reserved about capitalism, which underlies climate change and prevents action to abate it.

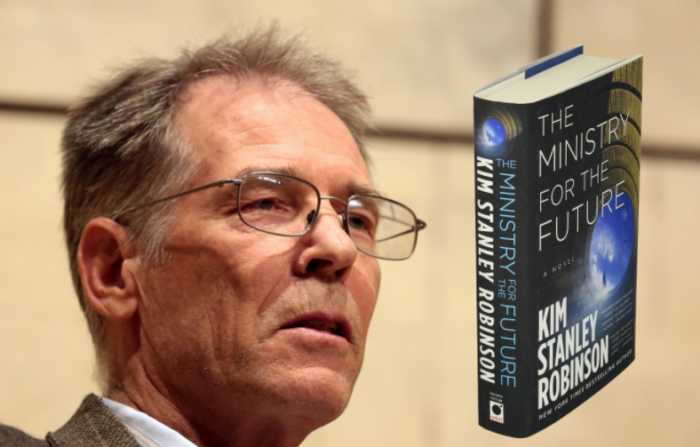

Kim Stanley Robinson makes a game effort to define a literary response to climate change in his latest novel, The Ministry for the Future. Robinson stands, arguably, as the doyen of “hard” (relatively realistic science-based) science fiction. He has earned this position largely on the strength of his Mars trilogy, which depicts the terraforming and colonization of the red planet (and, eventually, much of the rest of the solar system). In this and in many other novels, Robinson takes in both the broad sweep of his worlds—terraformed Mars, a world without European colonialism in The Years of Rice and Salt, the near future in his latest outing—and minute details of how things work. The reader of Red Mars, the first of the Mars trilogy, had better be ready for meticulous depictions of space shelters and tractors. Anyone picking up The Ministry for the Future will encounter excursions into the mechanics of geoengineering, Alpine mountain climbing, cryptocurrency, and more.

Robinson also earns frequent plaudits for the humanism of his vision. He identifies as a democratic socialist, and his books reveal an author deeply concerned with what makes life livable and pleasurable, whether on Earth, on Mars, or on board a generation ship as in his Aurora. Robinson “geeks out” with equal enthusiasm for the scientific and technical details traditional to science fiction and for the creation and implementation of fair, transparent decision-making systems. Terrible disasters occur frequently in his work, but Robinson never leers at them, never indulges in apocalypse porn, never valorizes suffering or violence.

For both the scale and the humanism of his vision and, one suspects, his high seriousness, literary gatekeepers have anointed Robinson as one of “the good ones” from the genre precincts. He deserves the praise, in that his work is consistently interesting and in that he seems like a mensch who deserves recognition and good things.

Robinson’s novels work as thought experiments, as visions of the future and the past, as a body of writing expressing a consistent value system. Do they work as novels? The answer to that question is considerably less clear, or maybe just somewhat painful to answer correctly. Nowhere is this dynamic in assessing Robinson’s work more in play than in The Ministry of the Future.

Long stretches of this novel take the form of meeting notes written by one or another member of the titular ministry, a UN body founded to combat climate change’s effects, headquartered in Zurich. Perspective shifts erratically across one hundred and six short chapters, from an omniscient narrator who speaks in educational riddles, to the two closest things to main characters (Mary, the UN bureaucrat in charge of the titular ministry, and Frank, an American aid worker struck with climate disaster-related PTSD) to assorted unnamed speakers relating this or that aspect of humanity’s attempts to mitigate and survive climate change between the 2020s and the 2050s. This can be, somewhat generously, construed as a deliberate attempt to play with the form of the novel. It can also be read as a book written in a hurry.

Two distinct types of set piece characterize the more conventionally depicted action in the book, apart from the riddles and reports: natural disasters, such as a harrowing heat wave in central India and a massive flood in Los Angeles; and meetings of central bankers. Robinson brilliantly conveys the former with queasy urgency and tragedy, and the latter are exactly as thrilling as you’d expect. Robinson gets across the lived existence of his two main characters, particularly their griefs and frustrations as they attempt to cope with disaster after man-made disaster, but neither of them are particularly distinct except through what happens to them over the course of the book. The other characters are similarly blank, conveyors of an idea or feeling or two.

The dashed-off quality of the prose and characterization in The Ministry of the Future can make it an ugly read sometimes, but as Kurt Vonnegut once put it in an encomium to science fiction, “to hell with the talented sparrowfarts who write delicately.” Whether or not they also implicate Robinson’s limitations as a prose stylist, the rougher literary edges of his latest work also reflect the urgency of the moment. Climate change is real and is going to change everything. In that context, delicate character development and finely honed prose constructions can seem irrelevant. Ideas and their impact—science fiction’s wheelhouse, at its best—are what matter.

What, then, are Robinson’s ideas? Here again one runs into the challenge of reconciling the joy a reader might feel in Robinson’s buoyant enthusiasm for ideas with certain harsh realities. “Mondragón, Kerala, MMT, blockchain, Denmark, Cuba, and so on,” a character says to another when trying to encapsulate the ideas that help turn the tide and save humanity. This list is made up of two things that are definitionally ideas (MMT, an acronym for “modern monetary theory,” and blockchain technology, the backbone of cryptocurrency), four locations standing in as metonyms for systems of governance, and the phrase “and so on.” This list exemplifies Robinson’s pell-mell, fiercely empiricist approach to politics. Take what works from wherever you can find it, Robinson tells us, slap it together, and be on your way, unconcerned about ideological labels or, indeed, context, like the radically different situations Cuba and Denmark are in. He can’t seem to help himself—he is what is today called a “process nerd,” eager to show off all the neat things he knows. It’s wholesome, if a little tiresome too.

Politics is a technology, Robinson tells us directly in a later chapter, one of his dialogues between unnamed speakers. For better and for worse, this belief defines his approach to the political problems climate change poses. In terms of hot-button ecological issues, Robinson comes out swinging for “geoengineering,” big technical schemes to mitigate climate change by doing things like throwing tons of reflective chaff into the air to bounce more sunlight away, cooling the planet. Between this and his embrace of the “Half Earth” proposal, where half of the Earth’s land surface is abandoned or “rewilded,” Robinson draws battle lines with others in the fractious ecological discourse.

Robinson also passionately advocates direct democracy and popular participation in small scale, local projects such as regenerative agriculture. But he is oddly reserved about capitalism, which underlies climate change and prevents action to abate it. Robinson shows he’s fine with critiquing capitalism, subverting capitalism, transforming capitalism—but seems incapable of imagining capitalism ending. Worker-owned co-ops, sure; workers’ control over the means of production and the governments that go with it, no. Governments don’t change much, either—with the exception of the overthrow of the Saudi royal family—even when said governments are responsible for terrible climate disasters. For a man who is possibly America’s most prominent self-described socialist writer, this is a peculiar lacuna.

So revolution hasn’t got much of a place in the book. Violence does, however. Throughout the book, a “black wing” that secretly murders climate profiteers and sabotages polluting industries abets the efforts of the titular Ministry. Robinson doesn’t linger on them but they prove crucial to the action of the book.

What isn’t crucial is any mass popular uprising aimed at seizing economic and political power. Mass use of technology, mass participation, mass equalization of status, yes; individualistic violence, sure; mass power, no. Mary and the Ministry begin the book dealing with central banks, national governments that resemble those of today, and the realities of the US Congress, and we end the book with all of them more or less intact. “How to change the world without seizing power,” as a book Robinson has perhaps read put it, is what this book implicitly asks. Violence is on the table, but seizing power isn’t. It’s a stumper, honestly.

In any event, for all of its flaws, how many books, especially novels meant for mass audiences, even make the reader think that much, as even a cursory reading of The Ministry for the Future demands? In many ways, good and bad, this is a book for its time. A reader can call it many things, but they can’t call it irrelevant. From a certain perspective, it calls into question the relevance of wide swaths of contemporary fiction. That’s an accomplishment few can claim, but one that Robinson can, with pride.

THE MINISTRY FOR THE FUTURE. KIM STANLEY ROBINSON. ORBIT BOOKS. 576 PP. $28.

Peter Berard is a writer and organizer who lives in Watertown, MA. For more of his work, check out peterberard.substack.com.