Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn

Written and directed by Radu Jude. Croatia/Czech Republic/Luxembourg/Romania, 2021, 106 minutes.

The curiously named 10th feature in less than 13 years by Romania’s 44-year-old Radu Jude begins with a provocation—several minutes of unsimulated sex. Jude is daring his audience to walk out or express outrage early, but then exposes society’s genuine obscenities for those who stick it out. Once the film’s proper narrative begins, the camera wanders away from the protagonist Emi (Katia Pascariu)—the star of the now-viral sex tape, a schoolteacher afraid she’ll lose her job as a result—and tilts up toward a billboard depicting an open-mouthed woman looking at a white dairy product, accompanied by the copyline “I like it deep.” Later, Emi will defend herself in front of parents who brazenly spout conspiracy theories about everything from COVID to “Hitler’s alliance with the Jews,” but object to having a teacher who once made a consensual sex tape teach their children.

In less dexterous hands this would be rote or sanctimonious, but Rude captures like few other filmmakers the fundamental absurdity of our times—the farcical mix of hilarity and horror that characterizes the increasingly puritan and reactionary direction of our culture. Whether he is turning his camera away from narrative toward documentation of the city (as with the billboard) or playing with ideas about superheroes and democracy (as he does in the makeshift trial), Jude turns observation into interpretation. Sometimes the only way to cope is to laugh. [★★★★] —Forrest Cardamenis

Scheduled for US theatrical distribution on November 19.

Benedetta

Co-written and directed by Paul Verhoeven. France/Netherlands, 2021, 127 minutes.

If you make it past the angry Catholics that might be picketing your local screening, Benedetta awaits with crucified arms. Paul Verhoeven’s latest is his answer to Ken Russell’s The Devils (1971)—i.e. another shocking middle finger (with three fingers pointing right back) to religious hypocrisy that is directed by a man who really seems gay but somehow isn’t, and is centered around a powerfully horny 17th century nun and the political structures bent on taking her down.

Benedetta herself is played by the resplendent Virginie Efira, who looks and acts like a young Samantha Jones, and expands her knack for portraying women characterized by their complex sexuality (first seen, by me at least, in 2016’s Victoria). Here, the titular sister discovers a heavenly talent for miracles and Godly tête-à-têtes at an early age, and an even more divine carnal appetite once the attractive Bartolomea (Daphne Patakia) joins the Italian abbey in which she resides. Not all is right in the convent, though, as the jaded Abbess (a delicious Charlotte Rampling) grows increasingly resentful over the young nun’s legitimate connections to Him and, more visibly, her.

The candlelit melodrama and comedy provide more than enough to satisfy even the darkest-souled heretic, all while Benedetta compellingly nails scapegoatism, bureaucracy, and misogyny to their respective crosses in its investigation of the destructive power of jealousy. That it manages to do all of this while being an out-and-out hoot is a testament to Verhoeven’s inspired take on his non-fiction (!) source material. This is a film that can masterfully speak to Our Current Times and still leave me room for a jukebox musical adaptation where Gay Jesus sings “God is a Woman” during a dream sequence. Praise be. [★★★★] —Juan Ramirez

Scheduled for US theatrical distribution on December 3.

Bergman Island

Written and directed by Mia Hansen-Løve. France/Belgium/Germany/Sweden/Mexico, 2021, 105 minutes.

Hansen-Løve’s latest turns the Swedish island of Fårö, home of canonized filmmaker Ingmar Bergman until his death in 2007, into a point from which to consider the artist as a young woman. It’s easy to see why you’d want to shoot a movie (or six, in Bergman’s case) there: The island in summer is coldly beautiful, with endless daylight, tall grasses, and perfect white buildings that evoke an otherworldly loneliness. Filmmaking couple Chris (Vicky Krieps) and Tony (Tim Roth) visit to find inspiration for their respective scripts, but Chris finds the island’s beauty oppressive and the spirit of Bergman intimidating.

Yet the “spirit of Bergman” is only a jump off point for Bergman Island, which shifts from something resembling a dialogue-based divorce movie into an impressionistic vision depicting Chris’ experience of balancing her craft as an artist with her roles as a wife and a mother. The protagonist of Chris’ script, played in the tender film-within-a-film by Mia Wasikowska, is clearly a reflection of Chris herself, and in turn Chris seems to be a reflection of Hansen-Løve (or at least a sort of response to her former relationship with filmmaker Olivier Assayas). It’s a romantic, thoughtful and at times slight story of lives both really lived and unexpectedly imagined, infused with such acute longing it can sometimes be difficult to bear. [★★★★] —Cassidy Olsen

Scheduled for US theatrical distribution on October 15 and VOD on October 22.

Titane

Written and directed by Julia Ducournau. France/Belgium, 2021, 108 minutes.

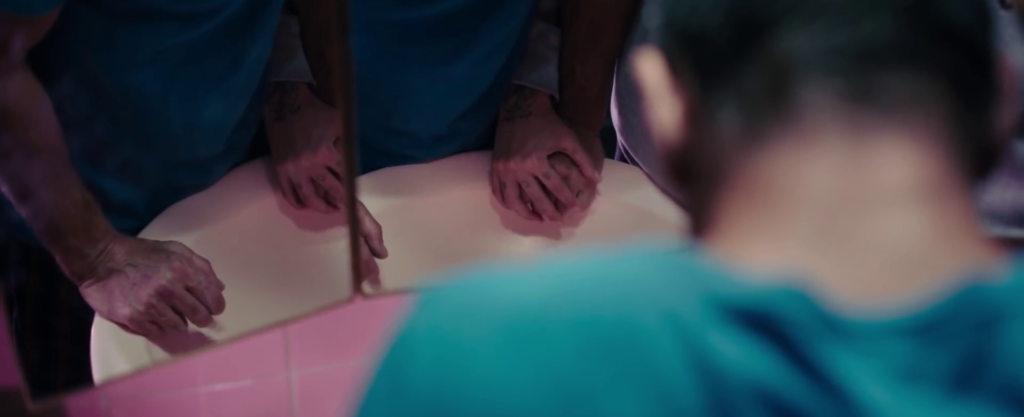

Despite all its body horror bravado, with bulging veins and torn piercings and pregnant bellies dripping motor oil, Titane is a sweet and even digestible film. This is thanks in part to Jean-Christophe Bouzy’s zippy and propulsive joyride editing, which never lingers too long on any one unsettling image. But Ducournau’s story itself is also fundamentally optimistic—alongside its larger stew of ideas about gender and sexuality, Titane is about the safety and acceptance one can find through chosen family.

In counterintuitive balance with the film’s energetic violence and emotional sincerity is its comedy, which springs readily from the odd-couple dynamic of our antiheroine Alexia (Agathe Rousselle) and her ‘roided adoptive father Vincent (Vincent Lindon). Both are desperately stubborn and largely delusional, and their dancing around each other makes for the funniest and most impactful scenes in the movie. Much has been said of the story’s shock factor, and while that may be one of the film’s greatest assets from a marketer’s perspective, the actual plot details don’t feel shocking in motion—they’re almost incidental compared to the images. Titane doesn’t propel itself on narrative transgressions alone, but pairs those provocations with a playful and economical visual language that keeps the focus on Ducournau’s characters. [★★★★] —Cassidy Olsen

Now playing theatrically.

Vortex

Directed by Gaspar Noe. France, 2021, 142 minutes.

Vortex, Gaspar Noé’s story of a woman with dementia (Françoise Lebrun, of 1973’s The Mother and the Whore) and her physically ill husband (Dario Argento, director of 1977’s Suspiria) is less provocative and more emotionally mature than his previous films. There is nothing as punishing as the prolonged shot of a rape in his reverse-chronological revenge film Irreversible (2002) nor as moralistic as the hysterical depiction of drug use in his carefully plotted Climax (2018), but Vortex packs the same formal wallop, making use of a split-screen from start to finish to give both characters their own claustrophobic frame even when they share the same space.

This technique presents some interesting challenges for the viewer; for example, it’s extremely difficult for the eye to follow both frames when the characters or cameras are simultaneously active. Ocular difficulty is not necessarily a bad thing: consider Goodbye to Language (2014), where Godard leaned into the messiness of 3D by creating separate images for each eye. Employing that technique despite the difficulties it presents for the viewer helps the film express ideas that words or narrative cannot. Vortex, by contrast, tends to avoid its conceit’s spectatorial disorders, and therefore its artistic possibilities. Instead, we tend to see one of the protagonists (the man, generally) sitting around while the other does something of significance, like smash up pills and put them in water or rip up a manuscript or wander outside. The implication is that it is more valuable to watch a plot develop than to watch a person sleep or type or sit—a notion disproved by decades of non-narrative filmmaking. In the absence of genuine formal audacity, what’s left is fairly standard realist filmmaking, although Noé deserves credit for treating illness and dementia not as metaphors but as the singular horrors they are. [★★] —Forrest Cardamenis

Scheduled for US distribution, no date yet.

Dig Staff means this article was a collaborative effort. Teamwork, as we like to call it.