Our first report on the 2020 New York Film Festival covered the Main Slate program, and our second the Currents and Spotlight programs. The films reviewed below played in Revivals.

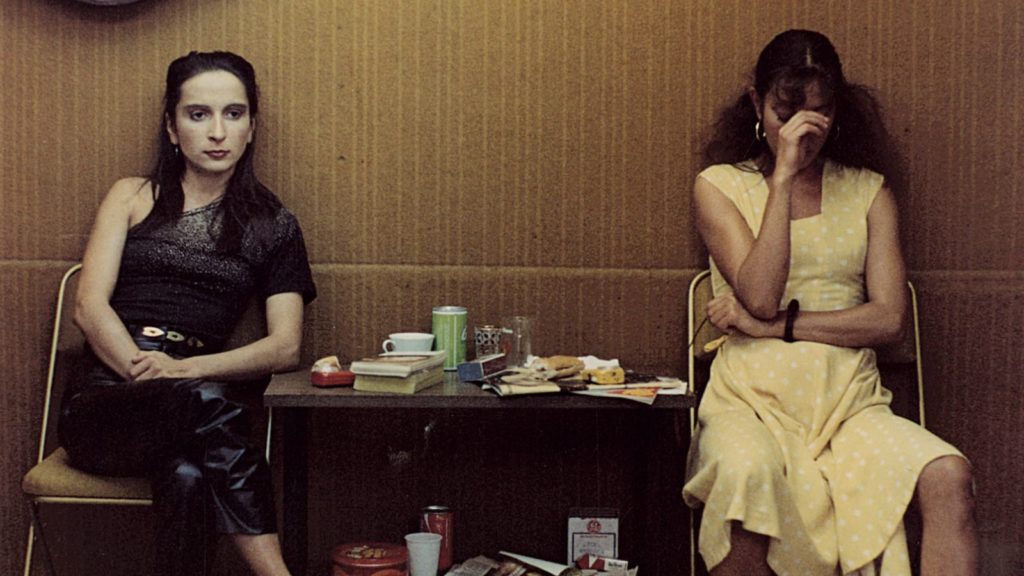

Simone Barbes or Virtue

Co-written and directed by Marie-Claude Treilhou. France, 1980, 77 minutes.

It is a truth universally acknowledged in today’s culture that all men are scum. Or, to be more specific, it is a sentiment that has only begun to be universally acknowledged—in blackly comic conversations online, or in the kind of scorn that can only present itself in the privacy of conversations with friends. Yet what makes Marie-Claude Treilhou’s newly (and beautifully) restored film Simone Barbes or Virtue is how it negotiates the particularities of this disdain: how it builds up like grime on a windowpane, how it obscures as much as it reveals, and how it is wiped away. The film focuses on Simone (Ingrid Bourgoin) as she finishes a shift ushering at a dreary porn theatre, meets a lover at a lesbian bar, and gets a ride home from a slightly lecherous man. Befitting the loose and breezy plot, Simone is a compelling heroine precisely because of her light touch. Her frustrations with her flaky girlfriend and the men who frequent the sleazy theatre she works at seem to be made of air, and it’s that capacity that allows her to uncover what is beneath the frequently repugnant surfaces of those around her. Her—and Treilhou’s—unstudied ambivalence presents both reality—scorn-inducing as it is—and possibility, sharp-edged and fragile as ever. [★★★★] —Hannah Kinney-Kobre

Meeting the Man: James Baldwin in Paris

Directed by Terence Dixon. France/UK, 1970, 27 minutes.

At some point James Baldwin films became a subgenre of their own, with notable entries including Take This Hammer (1964), Debate: Baldwin vs. Buckley (1965), and I Heard it Through the Grapevine (1982), some of which became excerpts in director Raoul Peck’s bio-doc slash Baldwin film-capstone I Am Not Your Negro (2017). To this still-incomplete list we can now add Meeting the Man: James Baldwin in Paris, a once-forgotten 16mm film object that played to some note at the Metrograph and BAM theaters in 2019 before its restoration and exhibition at this year’s NYFF. And based purely on the content of the film itself, one can’t help but suspect it was forgotten not because it lacks historical value but instead because its own director preferred it that way: I’ve seen Baldwin on film clowning many an interviewer over the years, but never quite like this.

In the first of Meeting the Man’s three significant passages, director Terence Dixon explains via narration how “Baldwin… became less cooperative” with the filmmaker’s own goals (which are essentially to make a simplified bio-doc of Baldwin-as-American-exile for an audience of primarily white Brits), leading to a very raw on-screen argument regarding how Baldwin should be presented (demanding to be photographed outside the Place de la Bastille, the author reiterates that he doesn’t want to be seen as “an exotic survivor” but instead framed as someone who “could be Bobby Seale”, which is a lot to ask of a white filmmaker who in his own narration gleefully refers to a nearby Algerian community as the “Harlem of Paris”). That argument begets the second passage where Baldwin hosts a salon at the studio of Beauford Delaney, and where the author’s implicit argument that more likeminded conversational partners will produce better material is quite demonstrably borne out—never moreso than when he works himself up into the exceptionally quotable line, “I can’t drive a truck, I can’t run a bank… I can’t lead a movement, but I can fuck up your mind.” Then finally after that, Baldwin gives the filmmakers what they wanted the whole time, a standard-issue same-old same-old face-to-face interview, where they ask him tired questions about his writing process and present outright racist interpretations of his work as if they were compliments (like when Dixon tells him, you are writing for white people, do you realize that?, with a particularly dopey excitement).

In a quote reproduced for the NYFF program that I can’t find printed anywhere else, the film’s photographer Jack Hazan describes Meeting the Man thusly: “Things don’t go to plan for [Baldwin] and the film crew when a couple of young Black Vietnam draft dodgers impose themselves on the American. Baldwin wrestles with being a role model to the Black youths, denouncing Western colonialism and crimes against African Americans while at the same time demonstrating his mastery and understanding of the culture he supposedly despises.” And yeah, there’s some hangers-on—and role model-ing and American-imperialist critique and all the other Baldwin film standards—but that description only serves to disguise what’s actually going on here, and what this film actually ends up capturing for the historical record: An image of Baldwin categorically rejecting the mindless racial graciousness that Dixon & co. project onto him, usually with a theatrical puff of his cigarette or a quick sip of a stiff drink, to instead deliver a performance that reflects back the selfishness and shallowness of not only those specific filmmakers but also the whole midcentury Anglo media culture that produced them. There’s a great and I must say timeless joke in Fritz the Cat (1972) where a white hippie bunny chick proudly boasts to a black crow that she’s “read everything James Baldwin’s ever written,” and with his performance in Meeting the Man Baldwin deconstructs that kind of statement with characteristic precision—and directly in the faces of the sort of people that probably would’ve said it themselves. [★★★] —Jake Mulligan

Smooth Talk

Directed by Joyce Chopra. US, 1985, 92 minutes.

At their malls, in their houses or in their cars, girls and women deal with “handy men” (James Taylor plays constantly). The smoothness wears off, and all that’s left is the feeling—unknowable yet inevitable.

Laura Dern is magnificent. At 18, she carried herself with the awkward grace that lands assertive teens in trouble. Adapting the Joyce Carol Oates story “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” (1966), Smooth Talk follows Dern’s Connie as she dances past her own limitations, exploring the uneasy tension between our comfort zones and the outside world’s devices. Warm yet melancholy, tender yet profoundly disturbing, it’s one of those movies you might not think to look at twice but are unshakable once you let them in—much like the sexual feelings our young protagonist feels blossoming within her.

What do all these mall trips and makeout rides with cute boys mean? As much as any teenage summer, they’re airy, sunlit, and intensely terrifying. [★★★★½] —Juan A. Ramirez

Available to rent at virtual.filmlinc.org beginning November 6, and at coolidge.org (among various others) beginning November 13.

Dig Staff means this article was a collaborative effort. Teamwork, as we like to call it.