Review: Easter Snap

Directed, filmed, and edited by RaMell Ross. US, 2019, 13 min.

Free to view at fieldofvision.org.

“It’s about something that happened when I was shooting Hale County,” explained filmmaker RaMell Ross, describing the relation between his short film Easter Snap and his sole feature to date, Hale County This Morning, This Evening (2018) during an interview with Filmmaker Magazine back in February. “But one of the rules for Hale County was no scenes, only shots or moments.” Easter Snap, in contrast, is just that—a “scene”—one focused, continuous, and containing great cumulative effect. Five men in Alabama, flanked by greenery in nearly every direction, walk into frame and begin to “resurrect the homeland ritual” of traditional hog processing—all quite unaware of the challenges about to encroach upon them, which like the film itself are intimate, fraught, and vital. And while the physical action Easter Snap depicts, “hog processing”, is a relatively unspectacular one, it is nonetheless demonstrative of true expertise, as well as of significant historical knowledge—and given that, Ross quickly finds symbols and suggestions of larger black American experiences within it. If pushed to find a comparison point, I might note that in all those qualities, Easter Snap is somewhat reminiscent of the formalist nonfiction portraits made by fellow contemporary American film artist Kevin Jerome Everson. But really, comparison points do it no justice: Ross’ new film is very clearly borne of his own cinematic language and impulses. The director emerges here not just as the authorial voice, but also as a crucial element of the dramatic interplay depicted in the “scene” itself.

For the sake of a closer reading, I’ll be describing Easter Snap in full; if you’re so inclined, perhaps break off here to watch it now.

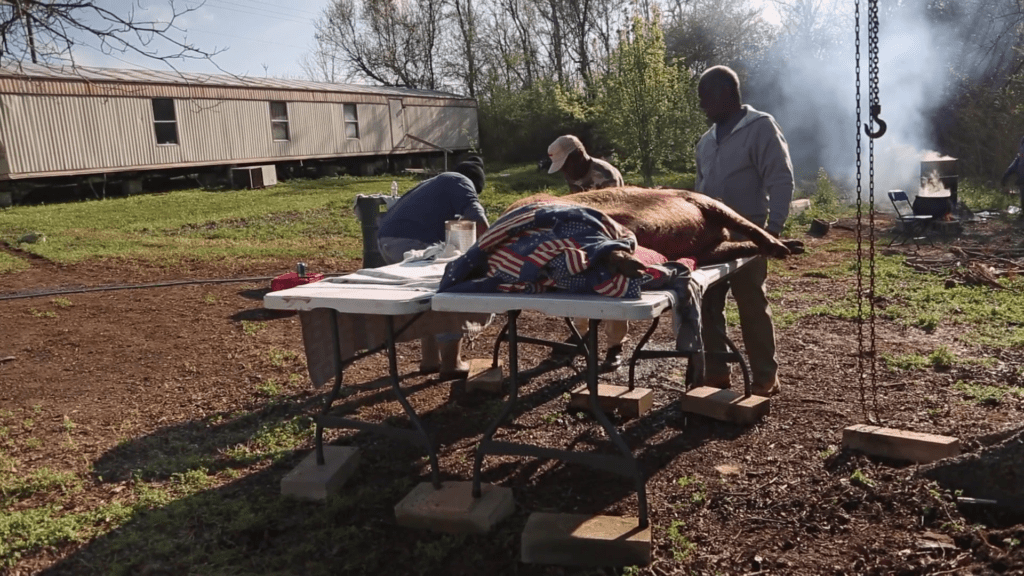

Introduced first is the landscape itself, patchy green earth and barren trees, surrounding a long one-story building and a shack in the back. Heavily accented voices are heard creeping up on the space from offscreen, then five people enter the frame, all older black men, all pulling a slaughtered hog by a rope they share the weight of. From there Ross offers a compressed depiction of the process (or at least its first steps), using a mixture of close-up insert shots and farther-off compositions: The hog is raised up, carefully shaved, and wrapped in cloth—a pattern of American flags from various eras, one of many links the film creates between the present and the ostensibly antiquated past—while cauldrons and barrels off to the side overflow with steam, and branches are stomped for the sake of a brushfire nearby (their snapping becoming a primary element of the audio track). In one of the insert shots, we see the fire itself for a second or two, and perhaps notice a pill bottle, prescription, empty, burning in the center.

Next there is a crucial sequence of shots where the foreground is kept in hazy focus (steam fills the frame) while a distorted score takes over the audio track quite suddenly (further emphasizing the sweltering, disorienting effect of the image). Then, at what is almost exactly the halfway point of the film, a participant—one Johnny Blackmon, who has been directing the action, seems to be the elder of the group, and is without one arm—suddenly collapses, falling outside the frame, and immediately diverting the focus of Easter Snap away from the process it ostensibly exists to depict.

There is no cut following the fall. After Blackmon has collapsed, the frame drifts toward him, and then swings roughly as Ross sets his camera down on the ground. Only then do we get a time cut, to Johnny sitting up and being cooled off—and meanwhile, the “hog processing” recedes to the background, performed as an afterthought by the others while two medical professionals check up on their elder. Following yet another time jump, the sliced hog is already being loaded into the back of a truck and the space is cleaned in some quick cuts. Easter Snap‘s final movement sees the frame assumes the view of a truck’s windshield as it drives through a road while two of the men—one being Johnny—speak with great friendliness and gregariousness from behind the frame. In the very last shot, the vehicle backs up, and the rearview mirror reveals four white men, two adults and two children, heretofore unreferenced, staring and waiting. One of the young boys waves at the frame, with a hell of a look, right before the film cuts to credits.

Following its premiere at Sundance and a run on the festival circuit, Easter Snap was uploaded online in September by Field of Vision, which describes itself as “a filmmaker-driven documentary unit that commissions and creates original short-form nonfiction films about developing and ongoing stories around the globe.” Some works uploaded by Field of Vision are accompanied by an interview with the filmmaker, or sometimes with other “field notes” illuminating and explicating whatever has been depicted in the given film itself. But Easter Snap has been offered sans any context beyond a one-sentence description—a lack of guidance that befits the picture’s approach to nonfiction form. Easter Snap movies back and forth between fairly straightforward nonfiction portraiture and increasingly mysterious evocations of elements and histories not actually physically present, sometimes even within the span of a single unbroken shot.

Even basic details about the film can prove relatively hard to grasp. The larger implications of its title, for instance, remains elusive to me; although my grandfather, currently living near Mobile, Al., suggests it may refer to “a ‘cold snap’ (weather) around Easter time”. On a related note, I also failed to discover any notes or reviews listing exactly where the film takes place, at least nothing more specific than “the deep south, Alabama”. But—if you freeze-frame the film at exactly the right second during the last shot, then flip the image, and then look in one of the rearview mirrors, you’ll discover that we’re somewhere off US Route 29 in Alabama, headed toward a town named Liberty. Which to some extent illustrates the potency and clarity of the symbols and subtexts being employed here—as well as the unusual extent to which they’ve been hidden beneath the surface, or even literally within the frame itself.

What’s consistent in nearly all the meaning those hidden prompts suggest, at least to me, is some kind of dialogue between past and present. More specifically, an awareness that significant histories are being lost to time every day, and yet also that histories we believe long gone remain here with us in the present; the film wise enough to understand both ideas not only can be, but rather must be, simultaneously true (and on a related note: Easter Snap is dedicated to the memory of two of its participants, Johnny Blackmon and Henry Taylor).

But more prominent than any subtextual meaning, at least while one is actually watching Easter Snap, is the radically transformative nature of the piece, which shape-shifts on its surface in response to whatever action is occurring in the frame at a given moment. First it establishes landscape; then a human presence; then character and diction; then a specific process; then suddenly, when the initial “plan” of the film is interrupted by something more urgent, the film itself responds, setting the image into action rather than pretending objectivity; and only when that matter is settled can the film can return to some sense of normalcy—except, of course, there is no such thing, as the haunting, undefinable sense of off-screen menace that pervades the final passage on the road seems to imply. Rich in surface detail and regional specificity yet unplaceable and irreducible beyond it, Easter Snap seems to bend to a psychology of its own, minute by minute and second by second: What begins as observational nonfiction then becomes personally involved with its subject, and in trying to step back to the original position afterwards, emerges in another realm entirely—that of poetic film-art.