During the COVID-19 pandemic, we’ll be publishing a series of reports on the status of local film institutions and theaters, which began with yesterday’s article regarding the Brattle Theatre. And in between those posts, we’ll be publishing articles and reviews concerning films that are currently available for home viewing.

The following review was originally published in a print issue of DigBoston last year, and was timed to a screening at the Harvard Film Archive. Some edits have been made to the original text, but for the most part it remains as originally written.

Film Review: Patty Hearst

Directed by Paul Schrader. US, 1988, 108 min.

Available to stream with subscription at Criterionchannel.com.

That Paul Schrader’s Patty Hearst is still a relatively unheralded film can be illustrated by the circumstances of its programming at the Harvard Film Archive last year. Writer/director Alex Ross Perry selected the print to show as part of a retrospective of his own movies specifically because he’d spent years waiting for it to be shown theatrically in another city, and had never seen it before—this even despite the fact that Schrader is among his “favorite filmmakers,” and to such an extent that the younger director had recently completed a midlength portrait film of his elder. “For years I have tried to get somebody to screen Patty Hearst so I could finally see how Schrader handles this particular female protagonist, as opposed to his usual lonely, angry man,” Perry wrote in the program notes describing the screening. “I think a print of this played once in New York, though I cannot imagine how or why I missed it.”

I myself was lucky enough to catch Patty Hearst at a very impressionable age, during my sophomore year of college, when I saw it projected from a VHS tape as part of an exceptionally insightful course on Schrader’s work instructed by my fellow Boston-area film critic Gerald Peary. To me, both then and now, the film seemed obviously central to any larger study of Schrader’s body of work, and beyond that, to be among his strongest films period: As morally complex and philosophically conflicted as First Reformed (2018), as formally dexterous and structurally inventive as Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985), and drawn with the same intense attention to regional and cultural texture as Blue Collar (1978). Aptly described by Scrader’s own mentor Pauline Kael as “overwhelming,” Patty Hearst is an all-encompassing study of a very particular set of American sociopolitical power dynamics—smuggled into cinemas under the guise of an more typically sensationalized biopic.

Now, to some degree, Patty Hearst really is a biopic, at least when considered in broad strokes. As is often true in that mode of filmmaking, the film is based on a memoir written by its subject, the real Patricia Hearst’s Every Secret Thing (1982). And it does indeed emphasize the most oft-reported details of Hearst’s life in a relatively linear manner—once again in line with the subgenre’s recurring tendencies. But in structure and function, Patty Hearst goes so far beyond what the biopic typically accomplishes: The film depicts a specific portion of Hearst’s life not to further sensationalize it, but instead to craft a larger and more expansive story about how power manifests itself within class structures, media culture, political organizations, and the justice system.

From a screenplay by Nicholas Kazan, Schrader’s Patty Hearst follows a four-part structure:

1. In the first movement circa 1974, Patty (Natasha Richardson) is kidnapped for ransom by members of the Symbionese Liberation Army, and then held captive in an extremely small closet while its members, led by General Field Marshal Cinque (Ving Rhames), alternate between threatening her life and indoctrinating her into their particular form of violent anti-imperialist radicalism. They also forcibly introduce her to their communal sex life: While no instances of assault or rape are depicted onscreen, the film carefully depicts the relation between psychological abuse and nonconsensual sex—a matter of significant importance especially given that whether or not Hearst’s participation was indeed nonconsensual became a central matter raised in trial afterwards.

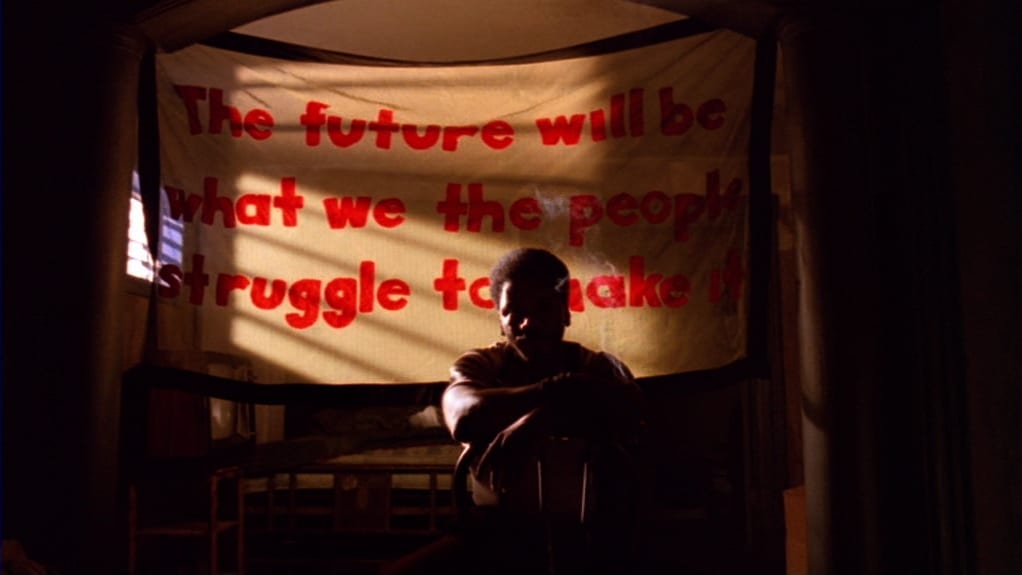

Much of this movement is depicted from Hearst’s subjective perspective, particularly the sequences in the closet (as seen above). In those legitimately frightening scenes, the frame is looking up from Patty’s low viewpoint, the image black other than the pure white blur shining through the space of the open door, and her captors illuminated by those back lights as though gods. When the film’s viewpoint finally moves outside the closet, many scenes then depict her captors speaking directly to the frame—once again placing us directly within the perspective of the necessarily passive Hearst (as seen below).

2. In the second movement, Patty is given the choice to “leave” (which she fears means death) or join the SLA (which she’s now discovered is in fact quite meager). When she of course selects the latter option, the film becomes something of an ensemble piece: We are officially introduced to other SLA members, including Teko (a transcendently funny William Forsythe) and Yolanda (Francis Fisher), and to their wider mission, which for the sake of space can’t really be detailed here, and isn’t necessarily all that relevant to the film itself anyway.

What is of supreme relevance is that the group is comprised almost entirely of white people, all being led by one sole black male, Cinque, and that the fetishization of the very idea of the black male by the former group is clearly what has kept many of them together—certainly far more than any shared anti-imperialist vision. That sense of collective self-deception among the characters allows Schrader to essentially transform the film, at least during this particular segment, into something of a satire, specifically by foregrounding the comically performative self-hatred of Teko—who at one point is seen in blackface, psyching himself up in the mirror like so many other Schrader-written characters before him.

3. In the third movement, following separate shootouts that leave Hearst implicated in significant crimes despite her initial kidnapping (and leave many other SLA members dead), Patty goes on the run across California with Teko and Yolanda, spending a series of nights in different flophouses and hideouts provided by vaguely SLA-adjacent friends. Leaderless, frustrated, and genuinely scared, the group begins to infight as the concept of political action gets sidelined entirely in favor of discussions about whether to run, surrender, or go out in a blaze of glory. But in line with the characterizations thus far, all those higher impulses are quickly swept aside in favor of more trivial conversations, mostly regarding Teko’s ongoing sexual frustrations—which he clearly prioritizes above whatever revolutionary charge he’s learned to disguise them under.

4. In the fourth and final movement, the group is captured by police, and Hearst is charged with a number of crimes allegedly committed during her time as a “member” of the SLA, including a bank robbery. At this point the film, for the remainder up to its Pickpocket (1959)-influenced ending (a Schrader hallmark), becomes something of a court movie—depicting in stringent detail the series of police procedures, psychological evaluations, court proceedings, and other matters that Hearst was quite literally forced to endure after having been liberated from a scenario that had seen her kidnapped, assaulted, raped, brainwashed, and then kept captive, first physically then psychologically, for an extremely long period of time.

The continuity of all these injustices, which the film lays out in depth and with an exceptionally intelligent editing rhythm, is not merely implied but instead an essential part of its entire design—at one point even a lawyer’s meeting is seen from an unreal angle high above the room, as if the camera were looking on from a sniper’s perch above a prison yard. Along those same lines, many of the compositions seen in the first segment depicting the kidnapping suddenly return in a rhymed or reversed form during this last segment, except with members of the SLA now swapped out for representatives of the United States justice system (as seen below).

Concurrent with the Harvard screening of Patty Hearst was a separate repertory program at both the Brattle Theatre and the HFA, “Make My Day: The Cinematic Imagination of the Reagan Era”, named after critic J. Hoberman’s new book Make My Day: Movie Culture in the Age of Reagan (2019). That program, per the notes accompanying it, “look[ed] closely at the often uncanny and absurd synchronicities between Hollywood cinema and American politics, especially during the years when the White House was occupied by former Warner Brothers contract actor Ronald Reagan.” Reagan, who of course left office very shortly after Patty Hearst’s theatrical release, is mentioned but once in Schrader’s film, where he’s referred to as “that pig fuck governor.”

But though the film is somewhat removed from the historical period of the Reagan era, Patty Hearst concerns itself directly with subjects, themes, and ideas that align with the above-quoted description of Hoberman’s book. That is borne out, I think, by Hoberman’s own description of Patty Hearst, taken from an article written for Artforum in 1988: “The connect-the-dots narrative proceeds from one media epiphany to the next,” he wrote, “the taped messages, the pictures of Patty/Tania posed in battle fatigues before the SLA’s seven-headed cobra, the automatic surveillance photos documenting the Hibernia bank robbery, the televised firefight in which the Los Angeles SWAT team incinerated most of the gang, Patty’s arrest and self-description as an ‘urban guerrilla.’”

Schrader’s film not only concern these “media epiphanies” quite directly, but indeed expands that same critique to include even itself. As the screen captures included in this article surely indicate, Patty Hearst is a film of people staring: Other characters staring at Patty, projecting their values and wants onto her; Patty staring back at them, calculating her position and trying to navigate with even less agency than she is normally granted; us staring at Patty, trying to read or interpret specific emotions and motivations within the hauntingly blank looks that she’s crafted specifically to protect herself from those around her; and finally in the last scene, Patty looking back at us, and right into the camera, as if to confront the inherently slanted media gaze that even this film itself would inevitably contribute to. Not just acknowledging but also confronting its own role in the never-ending employment of media culture to shape control, power, public-facing celebrity narratives, and even state policy, Patty Hearst‘s closing moments bring the picture’s many disparate segments into a clear and harrowing whole.