Film Review: The American Sector

Directed by Courtney Stephens and Pacho Velez. US, 2020, 68 minutes.

Available on virtual cinema platforms, including The Brattlite.

The American Sector plays like a travelogue disguised as conceptual nonfiction, or maybe it’s the other way around. But either way the concept is a strong one, and more than enough to sustain intellectual engagement across feature length: The film depicts slabs of the Berlin Wall currently located in the United States, accompanied by onscreen text identifying the location and short bursts of audio interviews with various passersby. By speedily documenting more than 40 fragments spread across 20 states (plus whoever’s talking nearby), Stephens and Velez create an unusually expansive pictorial tour of the country, editing different topographies and their attendant social classes against each other to reach a comprehensive view of American public life (as mediated by an imported central metaphor).

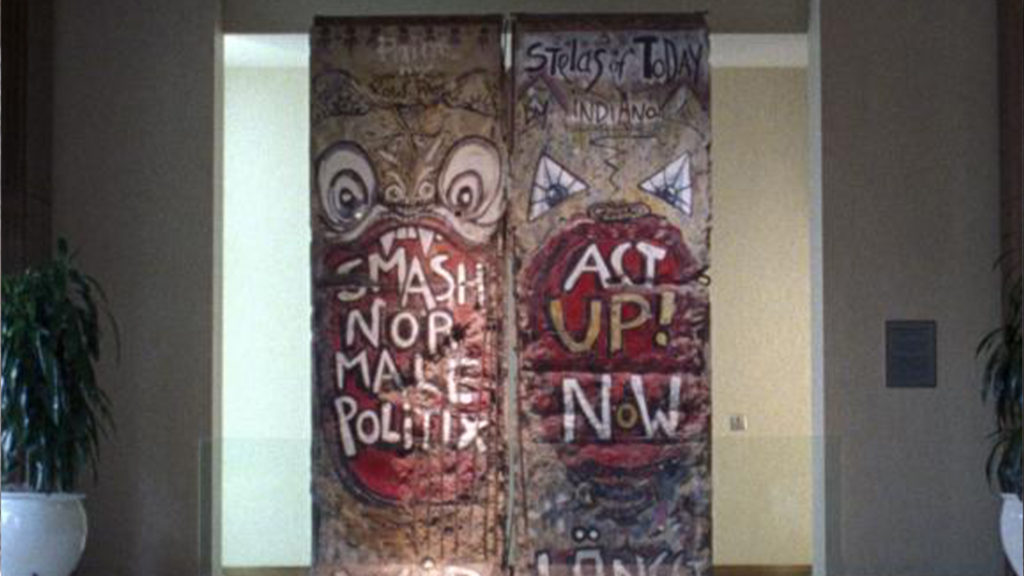

Maybe that sounds like an elevator pitch, but it’s not that sort of movie. The American Sector instead commits to noncommercial practice, rejecting narrative and obscuring the filmmakers’ own personalities to showcase regional, political, and social peculiarities instead. And its formal concept is kept up consistently enough so that whatever a given viewer decides to focus on—which could include (a) the different ways that “historical information” is presented in American spaces, (b) the different ways that people’s behavior changes in front of a camera, (c) the different reasons that physical segments of the Berlin Wall were purchased by Americans, (d) the appearance of the graffiti on the slabs themselves, or (e) the photographic qualities of the various landscapes being depicted—is determined more by the predilections of the viewer than by the film itself. The rigor pushes it to Rorschach status.

Which is not to say the movie is free of prescribed meanings. The American Sector is a film produced in America during the Trump administration and is literally “about walls,” so the political implications are obvious and ever present. As such they’re addressed directly—first by the interviewees, who collectively suggest a wide spectrum of domestic political discourse (comments are heard from citizens, scholars, college students, and even a CIA employee), and then also by the filmmakers, who include a few archival clips to push interpretive buttons (video footage showing people crossing the Berlin Wall at their peril circa 1988 is positioned directly following a scene of a man on the Mason-Dixon Line speaking very cogently about the connection between America’s repossessed fragments and its all-encompassing history of racialized violence, creating an editorial comment that seems to state the filmmakers’ perspective outright).

But now the film sounds like propaganda, and it’s not that either. More accurate to say that The American Sector studies propaganda’s mental and physical effects, like in a genuinely funny scene where three kids at a Reagan Museum present the American education system’s version of history by saying Gorbachev tore the Wall down “because Ronald Reagan told him to.” That scene’s not surprising in terms of content, but it basically exemplifies the whole film, which is full of comparably potent intersections between people, places, and received politics—and similar instances where a simple prompt reveals firmly established ideological guidelines.

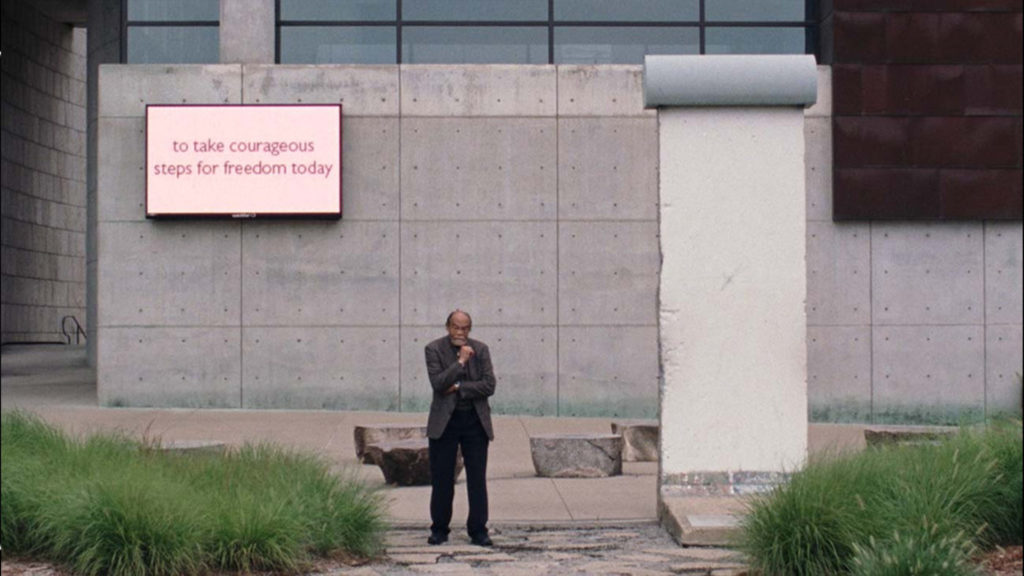

Down the same lines, the movie has a photographic integrity that comes from its rigid commitment to the concept. Most scenes begin with a fragment of the wall buried in American ground (one symbol loaded into another), then find people near the fragment interpreting what it means (betraying common American mistruths and prejudices in some cases, revealing crucial emotional truths in others), then expand by reframing the given fragment around visual details culled from the same location (usually something that’s funny or telling from a class perspective, like a shot where a segment of the Wall sits decoratively in the center of a corporate retreat while nearby suits play bocce). This formal approach creates a constantly refreshing portrait of Americans processing and responding to the symbols embedded within our public spaces… thus The American Sector does not make its own metaphors so much as it observes and depicts how we respond to the ones we’ve made ourselves.

Velez and Stephens shoot on 16mm stock, but don’t beautify their images too much. Some frames are casual and familiar (usually when the interviews are fully submerged within the sound mix, as in a film like El Mar La Mar, 2017), and others have a nearly industrial vibe (usually when they pose commentators onscreen with a deliberate stiltedness, as in a film like The Hottest August, 2019). But most potent of all is when the images and cuts are coded to emphasize the absurdity of the subject… At its very best, The American Sector records the inveterate preposterousness of what this country actually looks and sounds like. Like in a scene depicting a fragment of the wall at Universal Studios Orlando, which is flanked on either side by a roller coaster and a Hard Rock Café, and is presented by a guy who immediately defers to ironically promoting his employer for the camera—altogether creating a much realer depiction of the fully-corporatized American experience than anything fiction’s conjured lately.

The American Sector often locates overwhelming extremes of eccentric Americana just like that one, as though it were chasing after the modern cinematic equivalent of certain Grant Wood paintings or the regionally-specific side-jokes from the good seasons of The Simpsons (1989-). It’s not a comedy but there’s a handful of scenes and edits funnier than anything found in most recent ones.

There are some local angles on The American Sector also worth mentioning. First is that multiple slabs currently stationed in New England are featured, like one at the JFK Presidential Museum. Second is that both filmmakers have at least a tenuous professional connection to certain local film institutions: Velez studied and worked at Harvard’s Sensory Ethnography Lab during the 2000s, Stephen’s latest major project is an “all-archival film” featuring materials sourced from the Harvard Film Archive, and both have shown work at New England spots including the Brattle Theatre, the Camden International Film Festival, and the HFA itself. And third is that The American Sector was virtually exhibited by the local DocYard screening program earlier this year as part of their Spring ‘21 series, which occurred ahead of the film’s current release on virtual cinema platforms.

Most virtual programming of the last 15 months has been heavily promotional and left me deeply unfeeling, but the DocYard’s online events from the same period have stood out as being particularly inviting and humane. One reason is their commitment to accessibility, which goes beyond the usual boilerplate standards. Another is the very real sense of curiosity (probably the rarest quality in contemporary film programming) that guides the schedule, film notes, and talks, which right now are led by curator Abby Sun. To wit the conversation about The American Sector between Velez, Stephens, and Sun, which can be found on the DocYard’s Facebook page, reveals a number of reflections I’m quite glad to have heard, like Velez hinting towards the “historical timeline” that exists as the “b-plot” of the movie, and Stephens talking about how the search for a perfect “sound bite” quickly dissipated in favor of a more open approach to documentation, and Velez again talking about how they could do the whole project a second time by instead looking at the countless “[blank]-henge” monuments currently littering the American roadside.

They’re probably joking about that last one, but I think The American Sector suggests that such a project could have real artistic value, too: for the true aesthetic character of the American landscape seems to rest somewhere past its major cities and its rural outskirts alike, and with The American Sector both Stephens and Velez prove themselves quite capable of finding it. [★★★]

The DocYard will return for their Fall 2021 season later this year, with all screenings occurring both virtually and in-person at the Brattle Theatre. Season passes are now available priced at $49 for all eight films, see thedocyard.com for more details.