Aaron Sorkin is an American writer and filmmaker whose screenplays include those for A Few Good Men (1992), The Social Network (2010) and his feature-length directorial debut Molly’s Game (2017). Most recently he wrote and directed The Trial of the Chicago 7 (2020), which is now playing at the Kendall Square Cinema and will be available on Netflix beginning October 16.

We spoke for ten minutes earlier today via Zoom; the following transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

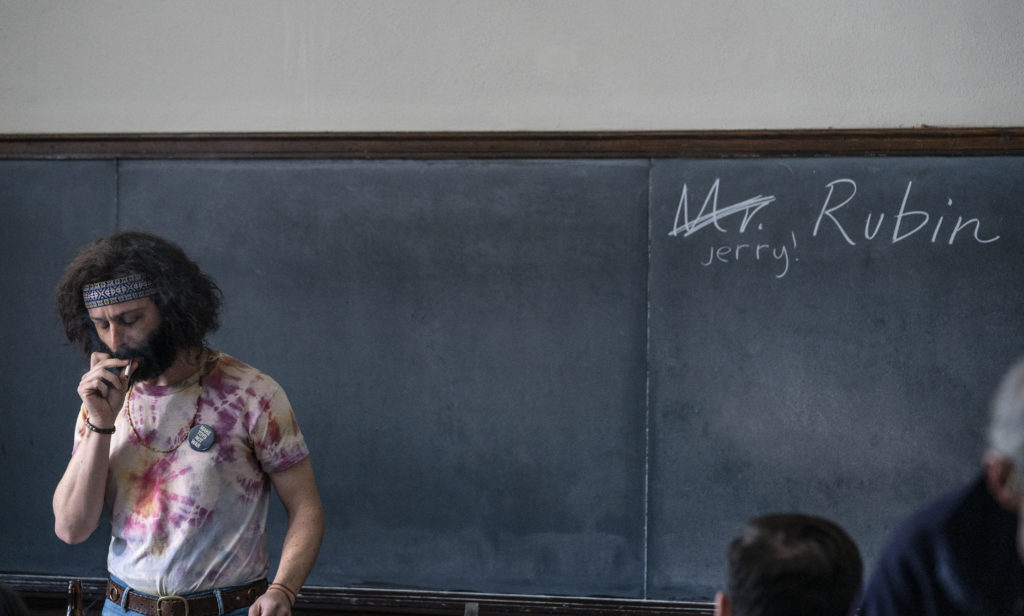

Do I detect a bit of Cheech and Chong in the depiction of Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin?

AARON SORKIN: You’d have to ask Jeremy [Strong] and Sacha [Baron Cohen] about that. But I know exactly what you’re talking about. I think that they set out to play Abbie and Jerry and it started to feel a lot like Cheech Marin and Tommy Chong.

Part of why I ask is that I’m interested in the effect of what we might call counterculture media on [The Trial of the Chicago 7]… because it’s about these nearly-mythic incidents of the late 60s, but then it’s shot almost like something from before that generation—it had me thinking of [earlier] Otto Preminger movies, and I know you’ve often cited Billy Wilder as an influence. How conscious were you of that generational tension in the aesthetics of the film?

What I was mostly conscious of in that regard was that I didn’t want the film to be about 1968, I wanted it to be about today. I didn’t want to lean into 60s iconography. I didn’t want us to be seeing a ton of peace signs or tie-dyed shirts, the psychedelic aesthetic. And I didn’t want to use the 60s protest songbook as a score—like, going into the theater you kind of know you’re going to hear “Fortunate Son” and “Sympathy for the Devil,” so instead we have a full orchestral contemporary score. That’s what I was conscious of.

So the memories that informed what you did depict in this film—would you say they were more from personal experience, or from other media?

Well I was in second grade when this happened, so there’s not much I remember from personal experience. Except for this one incident, now that you mention it.

When I was 11 years old, a few years after the Chicago Seven trial, I had a crush on a girl in my class named Jenny. And Jenny was volunteering after school at the local McGovern headquarters where I grew up in Westchester County. So I thought it’d be a good idea if I volunteered at the local McGovern headquarters too, so I could be near Jenny. One Saturday, they loaded all the volunteers into a couple school buses and took us to the next town over, White Plains, which is the county seat in Westchester, because the Nixon campaign motorcade was going to be driving through and we were to hold up signs that said McGovern for President.

I was holding up one of these signs—remember I was 11—when a 143-year-old woman came up from behind me, grabbed the sign out of my hand, whacked me over the head with it, threw it on the ground, and stomped on it. And the only political agenda I’ve ever had as a writer is the slim hope that that woman is still alive and that I’m driving her out of her mind.

Thank you for that story, I do appreciate it. I assume no epilogue with Jenny?

No, I’m afraid not. But she’s out there somewhere and I hope she’s well.

One scene that I like a lot is the one where the characters discuss the Port Huron Statement. Much like Abbie Hoffman does to Tom Hayden, I felt you in that scene communicating that you’d done the reading—had studied the written works of the people being depicted in this film. So I’m curious, after [having done so], how do you feel about Abbie Hoffman?

I have mixed feelings, and I think those mixed feelings are expressed in the film. The tension between Tom and Abbie in [The Trial of the Chicago 7] is a reflection of the Democratic Party today—the tension between the left and the further-left—the tension between people who want incremental change and to work through the system, and people who are tired of incremental change and want revolution. They are both valid positions, and I can play devil’s advocate with both positions.

But I wouldn’t have been able to get to that story without spending time with Hayden. You couldn’t get that from the books, you couldn’t get that from the 21,000-page trial transcript. It was Hayden that gave me a look into that world.

I ask because it’s a very potent [anti-Hoffman] speech that Hayden gives in that scene, talking about what might now be called electoralism.

You’re talking about the speech [where Hayden says], my problem with you is that 50 years from now when people think of progressive politics, they’re going to think of you?

That’s the one.

Yeah. And you know… that is the case. There are people on the right who when you say liberal to them, they think of 1968 and people passing out daisies to soldiers and trying to levitate the Pentagon. They think of people who are unserious. And Tom—and Abby—are both very serious guys. But that scene that you’re talking about, which ends with Abbie saying that he’s read Tom’s portion of the Port Huron Statement and everything that Hayden’s ever published… for me that is the end, or almost the end, of the personal story of the film.

Ultimately the movie organized itself into three stories told at once. [First] the courtroom drama, [second] the evolution of the riot, and how what was supposed to be a peaceful protest turned into such a violent clash with police, and third, Tom and Abbie. Two guys on the same side, that want the same thing, that hate each other’s guts, and that each think the other is doing harm to the movement… but in the end, come to respect each other. And the beginning of that is the Port Huron moment.

Perhaps this is because Spielberg himself was involved with your film’s production, but while I watched Trial of the Chicago 7 I felt like its depiction of the [late 60s] timeframe was in some kind of conversation with Spielberg’s depiction of the [early 70s] timeframe in The Post (2017). Did that connection occur to you, and if so, what’d you think about it?

You know, I watched The Post a lot. Both because I liked the film, and because it was taking place just a couple years after Chicago 7 takes place. So I was trying to pick up anything I could. And I do love that film, but any comparison to Spielberg is, I think, a mistake.