“Wonderland was, in effect, victimized by the smaller venues on Revere Beach. For some odd quirk of human psychology, people didn’t want to walk the extra distance.”

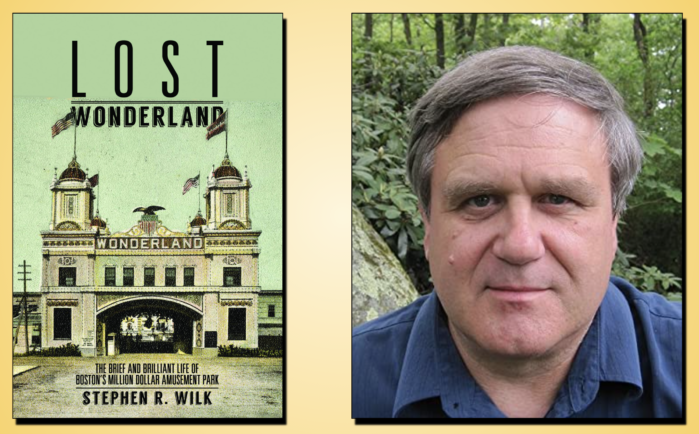

Stephen Wilk, author of Lost Wonderland: The Brief and Brilliant Life of Boston’s Million Dollar Amusement Park, holds a PhD in physics and has worked on laser propulsion at MIT’s Lincoln Labs. He’s also designed and built optical apparatus at Optikos Corporation and Cognex, is a contributing editor for the Optical Society of America, and wrote a book about ray guns.

His answers to our questions are amazing; talk about flipping a topic upside-down …

Prior to this, you established yourself as the galaxy’s leading expert on ray guns (How the Ray Gun Got Its Zap: Odd Excursions into Optics). You take a long time on topics and really sink your teeth in. Are you always harboring these arcane interests and sometimes they just turn into a book?

I’m always on the lookout for topics. I have a few things that I research long-term, but sometimes I stumble across some new thing that really interests me. That happens all the time with the Light Touch column I write for the Optical Society of America.

Of all the accounts of Wonderland in all its glory that you came across, what was the most unbelievable find—something that you never thought you’d track down or that really tied some other discoveries together?

The most wonderful find I came across was the book The People at Play by Rollin Lynde Hartt. This was a collection of essays he’d written for the Atlantic and later collected into a single volume with his own illustrations. Hartt was a Congregational minister, but his depictions of popular amusements were wry and sarcastic, and his descriptions of many of the attractions at Wonderland (he never names the park, but it’s clear from his descriptions and his illustrations that it’s Wonderland) deflate its pretensions. His pieces really are a wonderful antidote to the relentlessly positive and optimistic descriptions that the Wonderland publicists came up with, and which were reprinted pretty much intact by the newspapers.

My favorite is his description of the Fighting the Flames show. This was a spectacular demonstration of fire-fighting equipment and rescue apparatus given at a set built to look like a city square, and which was “burned” twice a day for shows. It really was a good show, from other accounts, but Hartt quickly goes to the heart of the production, saying that most of the spectators don’t realize that the professional firemen were in no danger, and that the people leaping into those rescue nets were really trained acrobats and trapeze artists. The people you really had to feel sorry for were the “improvident thespians as have laid by no money for the summer” who play the street characters in the show. “How they dodge the rushing engines, that Providence which watches over inebriates, babies, and play-actors alone knows.” Hartt’s takes … put everything into perspective as no other reports on the park could.

[Read an excerpt from Lost Wonderland here]

It seems like Wonderland was a big, bad small business-killer of sorts with the biggest and best of everything, while there had been many small-time operators in the years leading up to its opening who were probably impacted by its grand presentation. Was there any public sentiment that it was a Walmart or big evil Disney-like entity? Or was that not much of a concern at that moment in time?

You’re judging the past by the problems of the present. The intended “victims” of the big amusement parks back then were the other big amusement parks. Have a look into the history of Coney Island and you’ll see how George Reynolds, in building Dreamland (originally to be called “Wonderland,” and thus the source of the name for not only Revere’s Park, but for half-a-dozen others across the country) deliberately sought to put his competitors, Luna Park and Steeplechase Park, out of business. Similarly, when Floyd C. Thompson started surreptitiously building Vanity Fair at Point of Pines in Revere, he was directly competing with his own Wonderland. The small attractions along Revere Beach Boulevard weren’t hurt at all by the big parks.

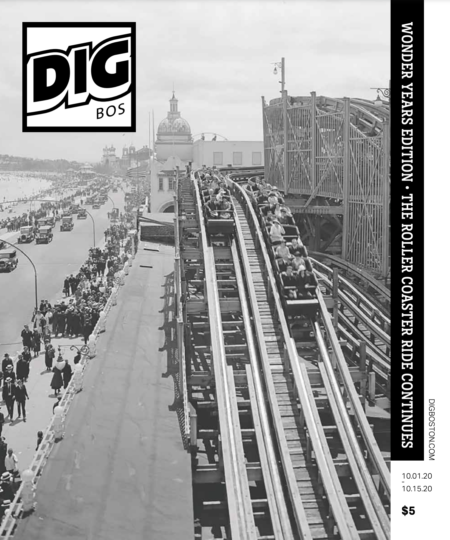

In fact, it was really the other way around—Wonderland was, in effect, victimized by the smaller venues on Revere Beach. For some odd quirk of human psychology, people didn’t want to walk the extra distance from Revere Beach to where Wonderland Park was, even though Wonderland had gone to the trouble of building a bridge from the beach right to the entrance to the park. This bridge was just about as long as the pedestrian bridge that goes from the beach to the Blue Line Wonderland stop (although it was about 300-yards south of where the modern bridge is).

Try walking across it sometime and then over to the Wonderland Marketplace Mall (which stands were the bulk of Wonderland Park was). It takes maybe 15 minutes, but people couldn’t be bothered to do it, and business at the park suffered for it. Even worse, many of those who had performed at the park or had ride concessions there actually built competing attractions on Revere Beach Boulevard—Louis Bopp had multiple carousels along the beach. Robert J. Blake and Charles Willard, who had performed in Chicago and elsewhere together and were both at Wonderland in 1908, afterwards got licenses for the Boulevard. H. H. Pattee, builder of the ride Love’s Journey, managed a smaller amusement park along the boulevard and put on female diving shows elsewhere. After the LaMarcus A. Thompson Scenic Railway first appeared in Revere at Wonderland, three more went up along Revere Beach. The man didn’t know the meaning of “market saturation.” All of these were more heavily patronized because you didn’t have to leave the beach, and Wonderland lost revenue because of it. It’s one of the reasons the park ultimately failed.

Did you come across anything about operations during the Spanish Flu pandemic?

Wonderland closed at the end of the summer of 1910—even though all the internet sites say 1911; I’ve seen the newspapers, it never opened in 1911. This was eight years before the Spanish Flu pandemic. So Wonderland was closed by then. I haven’t researched how the Spanish Flu affected other attractions along Revere Beach, but there might be a story in it.

How much of a roller coaster and amusement park fanatic are you personally? Do you have a favorite childhood memory from an amusement park? Was writing this book an excuse in any way to get out and hit a bunch of rides? Or were you mostly library-bound?

I’m a pretty big fan of amusement parks, myself. Unfortunately, my wife isn’t, in part because she gets sick on roller coasters. But I’ve been to Canobie Lake Park, Six Flags New England (formerly Riverside Amusement Park), Storyland, and Clark’s Trading Post. I’ve been to Disneyland and Disneyworld more than once, Busch Gardens, and elsewhere. Growing up, I went to Palisades Amusement Park in New Jersey and Freedomland (which was literally bigger than Disneyland, and located inside New York City). And, growing up near the Jersey Shore, I went on the rides there all the time, up until Sandy hit the shore.

I’m amazed at how you can find bits of Freedomland and the New York 1964-5 World’s Fair at Canobie Lake Park, Clark’s Trading Post, and the Lake George amusement park, if you know where to look. Or how Cornelius Vanderbilt Wood, who built Disneyland (but got written out of the official Disney histories, because he had a falling out with Walt), then went on to build amusement parks all over the country (including Freedomland and Boston’s own Pleasure Island) had a career that eerily resembles that of Floyd C. Thompson, who built Wonderland.

I did use the excuse of writing the book to revisit amusement parks, and also to walk the locations in present-day Revere, to try to imagine how it was back then. But I also spent a lot of time at the libraries in Boston, Revere, Winthrop, Lynn, the Revere Society for Cultural and Historical Preservation, and the library at Otis House in Boston. And a staggering amount of time in front of my own computer. You can find an awful lot, if you know how to query the internet, but it’s much more complex than typing in “Wonderland” into a search engine and expecting it to spit out everything. It was only by relentlessly following obscure clues and hunches that I learned about Hartt’s book, or Erwin E. Smith’s high-quality photographs of Pawnee Bill’s Wild West Show, or Harry V. Lawrence’s evocative description of his night ascension in a balloon over Revere one night in 1910.

Lost Wonderland: The Brief and Brilliant Life of Boston’s Million Dollar Amusement Park is available now on University of Massachusetts Press.

Dig Staff means this article was a collaborative effort. Teamwork, as we like to call it.