Better Luck Tomorrow

Co-written, directed, and edited by Justin Lin. US, 2002, 101 minutes.

Available on Blu-ray, DVD, and VOD, and to subscribers on Paramount+.

For the nearly 500 days between March 11, 2020 and July 2, 2021, I didn’t watch a movie outside my home. I didn’t watch movies in theaters, I didn’t watch movies at drive-ins, I didn’t watch movies shown outdoors to crowds of people sitting on blankets and lawn chairs—I didn’t watch movies except for when I was sitting on my couch and staring at the 40-inch screen that sits roughly 10 feet away.

Which I suppose is the way that most people watch most movies now, even before the pandemic made it mandatory. But whether necessary or not, I decided that if COVID was going to enforce moviegoing sobriety then I might as well go cold turkey. And for me the only way to properly break a cold streak like that was by watching a movie projected on 35mm in a theater I love where I could have a drink and not have to worry about the whole mask thing (at least not during the film itself). And that’s how it happened that my first moviegoing experience in about 500 days was seeing Hollywood director Justin Lin’s independently-made second feature Better Luck Tomorrow at the Brattle Theatre, which among countless potential back to the cinema programming choices is one that I really never could’ve predicted.

Better Luck Tomorrow played at the Brattle on July 2 as part of their “Reopening Week 2021,” which featured six films on 35mm scheduled across the theatre’s first six days of public screenings since March 2020. And in fact two of the six were back to the cinema programming choices that I never could’ve predicted—first Better Luck Tomorrow, and second Harriet the Spy (1996, screened to celebrate its 25th anniversary), which played alongside slightly more expected choices like Casablanca (1942) and Shaft (1971). Now, how’d the millennial deep cuts sneak in with the household names? Better Luck Tomorrow made it because it’s connected to a currently ongoing blockbuster series (if you know you know, but more on that below). And Harriet the Spy made it for being a standout at-home viewing: The Brattle’s own notes explained that “[a] silver lining during the ‘Pandemic Pause’ was revisiting a lot of nostalgic films, and this 90s dramedy was one of our favorites,” pointing towards the way that even theatrical repertory screenings are in dialogue with and directly influenced by the movies watched elsewhere on private time.

Reflecting on those circumstances got me thinking it was the right time to start up MOVIE DIARY, a new recurring article-category that’s designed to let our critics and reporters write about whatever movies they’ve been watching no matter why or where they’ve been watching them. Distinct from both our standard FILM REVIEW articles (which usually focus on new releases and special revivals) and our NOTES ON essays (which usually regard general subjects at greater lengths), the MOVIE DIARY space will be a venue for capsule-sized remarks on films and other moving-image artworks that fall outside the imminent release calendar. Maybe sometimes the movie in question will be showing at a repertory theater, or getting a new home video release, or something else like that. But just as often I expect the subject will be something random watched at home from a disc or hard drive—or even more likely, from a subscription-based streaming platform.

That last possibility is a crucial one, because the primary motivation behind this new article series is that it seems to me like film culture is currently dictated by a combination of distributor-chosen release dates and what’s on Netflix (or maybe the Criterion Channel, depending on who you’re speaking to), and so by writing more about the movies we’re viewing in our spare time the section might hopefully reach a more comprehensive, more engaged, and more truthful representation of where film culture’s really at right now than is accomplished by only focusing on the release calendar (although we’ll of course keep doing that as well).

As editor the only rule I’m enforcing is that the movies covered under the diary headline have to be accessible in some form, so that whoever’s reading can hopefully watch them too.

And it seems right to start with Better Luck Tomorrow, for at least two big reasons. One, because it’s the first movie I saw after the pandemic it’ll also rank forever among the most memorable theatrical experiences of my life, and is thus a good fit for the opening entry in a diary format. And two, because at heart I actually prefer Better Luck Tomorrow to all three other movies I saw at the Brattle that weekend … yes even Casablanca, which is of course very good but a little too down the middle for me if you know what I mean … like, I’m not comparing them, but to build off that phrase for another sentence, Better Luck Tomorrow is anything but down the middle … in fact it’s now best known as an off to the side entry in the Fast & Furious (2001-) franchise, because Lin transported the film’s best supporting character into that series’ complex mythos with The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift (2006).

Like Tokyo Drift, Better Luck Tomorrow is a contemporary juvie crime film. But where Tokyo Drift is just as narratively compromised and pseudo-campy as the 50s drive-in movies that kick-started the juvie crime tradition (which is fine, but hardly inspired), Better Luck Tomorrow approaches both parts of the equation with equal sincerity, guided by exactly defined character dynamics that excitingly criss-cross from a juvie focus to a crime one and then back again.

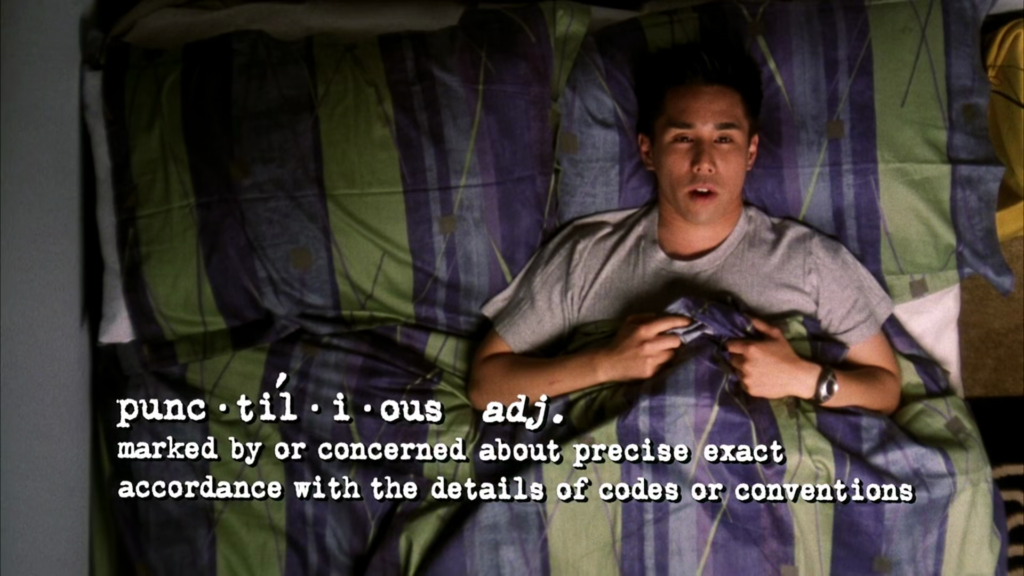

The story is that unofficial ringleader Ben (Parry Shen), Pesciesque hothead Virgil (Jason Tobin), De Niroesque elder Han (Sung Kang, as the future Fast character), and smartass extracurricular king Daric (Roger Fan), all high schoolers eyeing Ivy League universities (no phrase recurs more often than “college apps”), start running small-time schemes together on the side mostly because they’re “clever enough” to get away with them (it’s left for the audience to determine how much their relatively ambiguous ethnic identities contribute to their getting off scot free—for an early voiceover places the central irony in a more strictly academic context, noting that “our straight A’s were our alibis”). Their actions eventually draw the attention of mutual crush Stephanie (Karin Anna Cheung), which in turn draws the attention of her rich-kid boyfriend Steve (John Cho, giving a stealthily vulnerable and very funny performance as a kid who hasn’t grown into his own intellectual pretensions yet), which in turn puts everyone on the path towards a murder already revealed mystery-style during an unnecessary prologue scene (the film would likely play better without the foreshadowing, because part of what’s so good is how each new scene leads the characters further into the pot until they’re boiling without even knowing it).

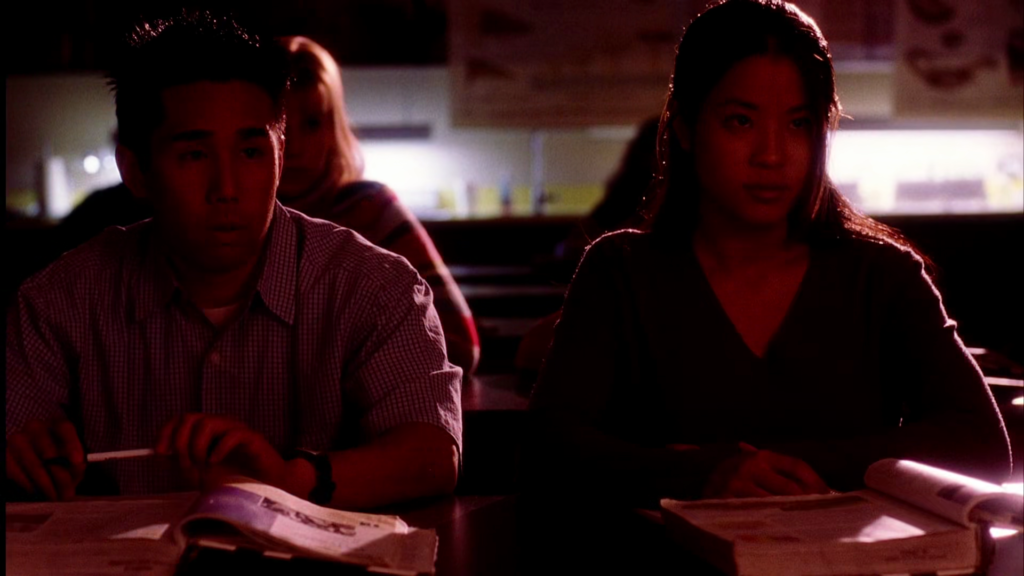

The screenplay, by Lin, Ernesto Foronda, and Fabian Marquez, is very perceptive at dramatizing moments where teenagers’ performances of masculinity and maturity inadvertently melt into something more fraught and real. Like one scene where a study group suddenly gains a sexual undercurrent neither party knows how to deal with (Shen and Cheung are beautiful as two people too anxious to start hooking up with each other), or another where a fight at a house party gets a little too edgy for even the fighters involved. And the performances match that messy youthful energy with a surfeit of sharply observed details, like tough-guy line readings and theatrical cigarette puffs the characters obviously learned from other movies.

Other movies cast a large cloud of smoke over Better Luck Tomorrow. Lin borrows color schemes, costumes and even his title from John Woo’s A Better Tomorrow (1986), which is first on the list of films these characters have definitely seen—Virgil cites star Chow Yun-Fat by name, and Han rips cigarettes just like him. That adds, not subtracts. Part of what makes Lin’s own film so exciting and thoughtful is that it’s not only thinking about what films these characters have definitely seen, but also thinking about how those films have influenced these characters: Better Luck Tomorrow locates the social advantages, sexual upsides, and psychological boosts that come for a young person who begins playing a role, then expands out deeper by depicting a series of incidents where the same tendencies lead the characters onto grounds they’re not so comfortable with. And it complicates that theme the whole time by keeping the lead characters framed as protagonists even when their actions begin to drift further towards ostensible villainy.

So eventually Better Luck Tomorrow feels more like a true crime story (where unresolved tragedy often comes as part of the package) than it does a juvie crime movie (where the characters usually come of age like most others), establishing simple but solid psychological character profiles that drive the narrative towards genuine melodrama rather than just arriving there cheaply by formula.

If Better Luck Tomorrow has an obvious flaw it’s that Lin’s direction follows the lead of his characters too closely, imitating a wide variety of compositions, formal modes, and camera tricks established by directors that were fashionable in the 10 or so years before it was made. There’s hints of Trainspotting (1996)-era Danny Boyle, Fight Club (1999)-era David Fincher, and most of all Scorsese and Goodfellas (1990), which is blatantly imitated from start to finish. When I first saw Better Luck Tomorrow about 12 years ago, that struck me as limiting, and below the standards of the screenplay. But now it appeals to me more, once again for at least two big reasons. One, it matches up with the psychology of the characters. And two, when compared with the current state of American genre films, where even the good ones seem to have been assembled nearly entirely by citation, Lin’s formal lifts seem almost quaint.

The same could be said for whatever aesthetic limitations one might ascribe to Better Luck Tomorrow, which features a lot of blown-out lighting and unkempt cuts surely necessitated by its small budget, tight schedule, and novice crew. Yet it still establishes a certain pictorial quality—slick and poppy but highly disconcerting, right on since the setting is a gated community in California circa 2002—that arrives mostly on the inherent strength of its 35mm cinematography. Part of that is the filmmakers, but another part is just the format itself, which adds qualities of its own during both production and projection (a lot of the blown-out images actually look pretty cool in a theatrical setting, especially when the warped colors originate from a light source contained in the frame itself like seen above).

Which is all to say that seeing a film on film for the first time in well over a year, I was reminded once again of something I basically always knew, which is that the variety of color, level of sharpness, and richness of texture displayed by even a small-budget commercial production of the so-called celluloid era very clearly outmatches the cheaply post-tinted, textureless, made-for-television look of modern commercial movies shot and distributed on digital formats. And so for reasons that had little to do with the content of the work itself, seeing Better Luck Tomorrow at the Brattle after my 16-month layoff was yet another reminder of the specifically cinematic qualities that were lost when a combination of industry power structures and changing societal habits displaced film-based theatrical exhibition as the centerpiece of movie culture in exchange for mid-quality digital video files designed to be seen at home instead. [★★★½]