I don’t have to tell anyone who’s lived more than a few years of adulthood that things that seemed one way when we were on training wheels don’t always stack up when you look back years later. In the past couple of months, I’ve learned that certain works that I found critically inspirational throughout my adolescence and my quasi-intellectual development are rather fraudulent, and I suppose I’m writing this in order to come to my own terms about whether it’s OK that I was deeply moved by these apparent hoaxes and to grapple with the notion that a number of my heroes stretched the truth, reportorial or otherwise. Hopefully it serves to help some readers, too.

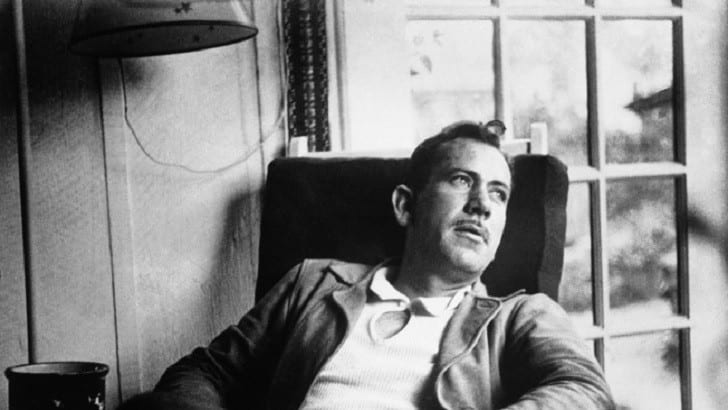

My standout disappointment of this sort comes from the author and all-around icon John Steinbeck, a giant I’ve come to not merely admire but consider an authority so great that his word could be taken on any subject, be it politics or love. I’ve read and re-read his amazing staples, but none of his books kicked me quite like Travels with Charley. Rather than encountering Steinbeck’s travelogue in a classroom like so many others, my first-ever Dig editor, Joe Keohane, recommended Steinbeck’s search to understand our country’s fast-shifting identity, and for the years that followed I intensely worshipped aspects from its cadence to its dead-on foresight of the soulless plastic nation we now live in. I even came close to writing an entire coast-to-coast account of my own based on this mainstream but still cultish classic.

Unfortunately, thanks to years of rugged gumshoe file-digging by ace journalist Bill Steigerwald for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and Reason magazine, it’s now quite clear that, among other cardinal sins, Steinbeck fabulated interviews and stayed in plush hotels instead of honoring his stated mission to experience the unglamorous unfolding of America’s uncomfortable cot, rotten lumps, cross-bar, and all.

Considering it now, I suppose it was naive to put much faith in Charley as a literal source in the first place; Steinbeck was a top-tier author when the written word ruled the world, and the idea of him sleeping in meager quarters is almost like Kanye claiming he hiked the Appalachian Trail. Since recently accepting the let-down, I’ve chalked up the deception to the author’s disregard for standard journalistic practices; Steinbeck, of course, was best known for his invention.

I’m happy to trace over such let-downs for days. Another one involves the Stanford Prison Experiment, which I’m not going to attempt to explain in this thought beyond saying that, like Charley, the famous psychological adventure in which an elite professor claimed he transformed young men into savage beasts was most likely at least tainted by opportunism and ego.

As for how I’ll use this knowledge from now on… Instead of worrying that I put too much stock in faulty narratives while coming of age, it probably makes more sense to just better calibrate my bullshit radar moving forward. A lot of people go through their entire lives repeating utter nonsense that they could have easily corrected with a Google search, and from that angle it’s hard to see how shining light on past misrepresentations could be negative at all.

A Queens, NY native who came to New England in 2004 to earn his MA in journalism at Boston University, Chris Faraone is the editor and co-publisher of DigBoston and a co-founder of the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. He has published several books including 99 Nights with the 99 Percent, and has written liner notes for hip-hop gods including Cypress Hill, Pete Rock, Nas, and various members of the Wu-Tang Clan.