“From everything I’ve seen, it was the first … trial of the century.”

In 17th-century New England, the bloody Pequot War pitted colonial settlers from England against indigenous inhabitants. The war began after indigenous communities became increasingly upset by the settlers’ land grabs, and during the conflict, the colonists indiscriminately killed Native American warriors and civilians alike.

Yet amid this worsening environment, a relatively unknown legal case in Plymouth Colony set a precedent for justice—the trial by jury of three settlers for the murder of an indigenous man named Penowanyanquis.

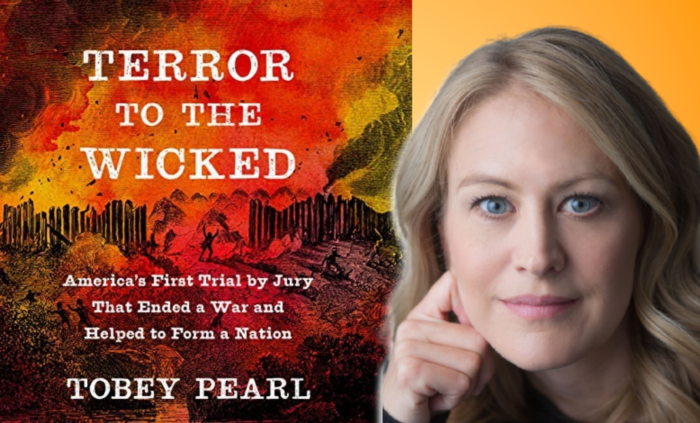

This is the subject of a new nonfiction book, Terror to the Wicked: America’s First Trial by Jury That Ended a War and Helped to Form a Nation by author Tobey Pearl. Beginning out of Pearl’s personal family research at the New England Historic Genealogical Society in Boston, the book takes readers back in time almost 400 years to the scene of the crime and the colonial meetinghouse-turned-courtroom where the verdict was delivered in 1638.

“From everything I’ve seen, it was the first landmark fully-developed jury trial of the era—the trial of the century, kind of,” Pearl said in a phone interview. “Certainly, there had been other meetinghouse trials predating this,” but such trials were “for small infractions,” such as a “cow trespassing on someone else’s land.”

This was far more serious. A group of four escaped indentured servants attacked Penowanyanquis, a member of the Nipmuc tribe who was returning from a trading mission in valuable beaver pelts. The group’s ringleader, Irish immigrant and Pequot War veteran Arthur Peach, allegedly stabbed Penowanyanquis with a dagger—a rare weapon for an indentured servant, according to Pearl, who goes into further detail about it in the book.

The wounded Nipmuc trader escaped, living long enough to describe his murderers to the founder of Providence, Roger Williams. A manhunt ensued, with Williams’ young indigenous slave Will playing a key role in tracking down the killers.

Pearl notes that much historical writing “[focuses] on a handful, one or two main players, who happen to be men.” She sought a different approach in her book: “I wanted each person, each human being in the story, to carry full weight, create a global portrait, as close as I could get to the identity of that person. It took me a very, very, very, very long time to do that.”

This research is reflected in her explorations of Penowanyanquis—“we know quite a bit about him,” she said—and into Will, whose identity she delved into through a close reading of Williams’ writings.

“None of this would have unfolded as it did without Will’s hand in what transpired,” Pearl said.

Will helped identify the killers, and although one of them escaped confinement and fled all the way to a refuge in Maine, the remaining three were brought back to Plymouth for the historic jury trial, presided over by the colonial governor and Pearl’s ancestor, Thomas Prence.

Pearl comes from a legal background herself, having worked as a nonprofit attorney and served as a juror in a criminal trial. She came across the long-ago case while doing family genealogical research at NEHGS after receiving a holiday membership from her husband, novelist Matthew Pearl.

“I was shocked I had never heard of these events,” she said. “It was not anywhere in history books. It’s such a fascinating moment that kind of encapsulates so many important issues.”

The Pequot War was an especially brutal war, according to Robert J. Allison, a professor of history at Suffolk University and the head of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts.

“Massachusetts Bay invaded the Pequot Territory and tried to eliminate the people—burning their main town on the Pequot River, selling the survivors into slavery,” Allison wrote in an email. “The Pequot River was renamed the Thames, and the site of the Pequot town became New London, in an attempt to remake the map. So complete was the devastation that Melville named his fictional whaling ship the Pequod for this eliminated band.”

Pearl called the era “a treacherous time to be alive.”

“Indigenous people living in that situation navigated unfortunate circumstances,” she said. “As battles were being fought, power shifted from one base to another. They were very complicated, difficult times. Aside from everything else, there was high mortality, from the settlers to the indigenous people. It was a very rough, difficult time to be alive in a time of war.”

She researched the case in many ways, even creating a map of the area as it would have looked almost four centuries ago with input from historical geographers Bill and Kristen Keegan.

“They donated an unfathomable amount of time,” Pearl said.

An unusual aspect of the case is that the attack took place in an area where there was no clear jurisdiction. Three high-ranking colonial officials—Prence, Williams and Massachusetts Bay Colony Gov. John Winthrop—sorted out the issue of who had jurisdiction.

“The three different colonies all had different conceptions of what should be done,” Allison said.

He noted that there were sensitive issues relating to indigenous communities of the area. Penowanyanquis was from the Nipmuc tribe and had been discovered by members of a separate tribe, the Narragansett, while the crime scene appeared to be in Narragansett territory.

“There were all very complicated overlapping jurisdictions,” said Allison, who also noted that in the Pequot War, the Narragansett had sided with the colonists and that an unsatisfactory resolution to the murder case might have influenced the Narragansett to change alliances.

Ultimately, because the four indentured servants were from Plymouth, the case ended up being tried there.

Jury trials in Plymouth Colony date back to a 1626 order by the colony’s first governor, William Bradford. This historic piece of parchment is preserved at the Plymouth County Registry of Deeds in an annex. Pearl visited the annex to photograph the document.

As Allison points out, jury trials had existed in England and were a “very important protection people had, trial by peers,” although in England this initially only extended to noblemen, with commoners being tried by magistrates.

In the book, Peach and his confederates were tried by a jury of 12 peers.

“What I was eager to do was get into the minds of jurors as much as possible,” Pearl said.

She said she was fascinated to learn that men engaged in grueling subsistence farming, with presumably “no time for leisure and the pursuit of reading,” actually had “remarkable” libraries and “a range of topics they concerned themselves with in discussion and consideration.”

“It surprised me,” she said. “I think it helped shape the verdict.”

As for that verdict, she said, “there was no way anyone could have said with certainty what the outcome would be. They were truly prepared for it to go either way. There were concerns in either direction.”

There was a decisive outcome, and it left Pearl thinking about the concept of justice in the courtroom and beyond.

“Sometimes people step out from how they identify themselves,” she said. “They put themselves into someone else’s shoes, extend every privilege warranted to someone else.

“It’s easy to say, Of course they should do this, of course it’s how it should be. But from 400 years ago to today, sometimes it’s hard for people to do.”

In 1638, she said, “they stepped forward to say a terrible injustice had happened. You can only wonder, Why were there not more conversations about the nature of the Pequot War too?”

Rich Tenorio is a writer and editor whose work has appeared in international, national, regional and local media outlets. He is a graduate of Harvard College and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. He is also a cartoonist.