“I think it was important, a way of restoring their humanity, to give them back their names.”

When UMass Amherst poet and professor Martín Espada would go to Bunker Hill Community College as a guest lecturer, he realized that the campus had a connection to Boston’s past. Bunker Hill was built on the site of the former Charlestown State Prison, where Italian immigrants Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti were held prior to their infamous execution in 1927.

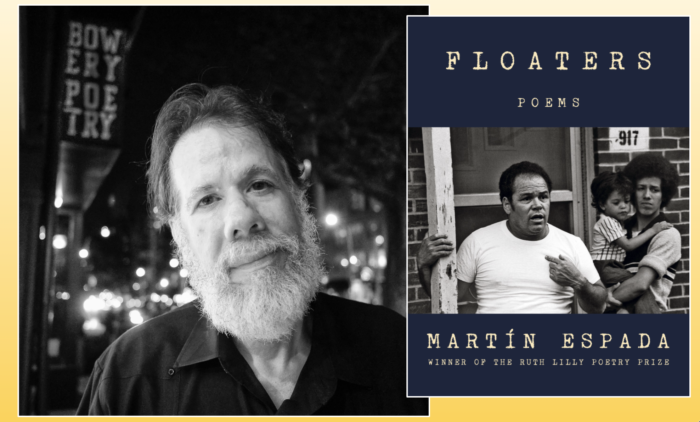

The Sacco and Vanzetti case has haunted Espada ever since he learned of it while a law student at Northeastern in the 1980s. And perhaps it has also haunted those who were involved in its outcome—including William Hendry, the then-warden of Charlestown State Prison. That’s the premise of “I Now Pronounce You Dead,” a poem that appears in Espada’s new book, Floaters, published by W.W. Norton & Company.

“This book is shot through with Massachusetts,” Espada said. “It’s where I have lived since 1982—almost 40 years. It’s who I am. I’m certainly influenced by the stories we tell and the stories that need to be told about the state of Massachusetts.”

One such story is the Sacco and Vanzetti case, evoked in a unique way in “I Now Pronounce You Dead.” The poem depicts the execution of Vanzetti through Warden Hendry’s eyes. Vanzetti’s calmness immediately before his execution contrasts with the guilt-wracked warden. Ultimately, Hendry incurs a fate similar to that of the Greek mythical figure Tantalus, who is condemned to see the food he reaches for disappear beyond his grasp. In Espada’s imagined version of events, the warden sees grains of rice fall off his fork when he tries to eat following the execution.

“This becomes Warden Hendry’s curse at the end,” Espada said. “He can feed himself no more. The hunger feeds on him. He is condemned as a ghost. No matter how kind he was to Vanzetti, he was still on the wrong side of history. That’s where I put him—and that’s where he belongs.”

“I Now Pronounce You Dead” was selected for The Best American Poetry 2019 anthology edited by Major Jackson. It was also published in the New York Times magazine in January; poems for the magazine are curated by former prisoner and current poet and lawyer Reginald Dwayne Betts. The poem has a resonance at Bunker Hill.

“Now [the Sacco and Vanzetti case] is widely recognized as a grave injustice, and the immigrants keep coming,” Espada said. “They keep coming at Bunker Hill Community College. There’s a delightful, musical variety of languages you can hear in the hallways. It’s the polar opposite of what was intended by the social forces who wanted to destroy Sacco and Vanzetti, the same social forces trying to repress immigration at the same time.”

Immigration is an important subject to Espada. His late father Frank Espada was from Puerto Rico, the son of a former mayor of the city of Utuado. When Espada himself worked as a tenant advocate in Greater Boston during the 1980s, the tenants he defended included many immigrants from Latin America. As he transitioned from the law to poetry—his achievements in the latter field include winning the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize—he continues to speak up for immigrant rights. He has grown concerned over the anti-immigrant sentiment of recent years.

The title poem, Floaters, is based upon a post from a secret Border Patrol Facebook group called “I’m 10-15.” A 2019 ProPublica investigation found that within the group, someone had questioned the accuracy of a photo of an immigrant Salvadoran father and his infant daughter who drowned trying to cross the border. As Espada explains in an endnote, drowned migrants are called “floaters” by some in the Border Patrol. The Facebook poster speculated that this image looked too perfect to be real: “I’m not trying to be an a$$, but I HAVE NEVER SEEN FLOATERS LIKE THIS, could this be another edited photo.”

In the poem, Espada insists that readers remember the drowned father and daughter not as “floaters” but by their actual names.

“Not by coincidence, people who saw the photo once it went viral started using their first names, over and over again, as if we knew these people: Óscar and Valeria,” he told DigBoston.

“Their full names were quite a bit longer: Óscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez and Angie Valeria Martínez Ávalos,” Espada noted. “It struck me that there was a tension between the word ‘floaters,’ that deprived them of their names, and the names themselves: Spanish, musical, to be spoken aloud. The names had their own poetry.”

And, he said, “I think it was important, a way of restoring their humanity, to give them back their names.”

Another poem, “Jumping Off the Mystic Tobin Bridge,” evokes Espada’s days as a tenant advocate defending Latino immigrants who were also stereotyped. In the poem, a cabbie driving Espada home from a day of work in Chelsea warns him to be careful because the immigrant city has “a lotta Josés.” The poem’s narrator tells the cabbie, “I’m a José.” The narrator continues, “He still wanted to know what I was doing there. I’m a lawyer. I go to court with all the Josés.”

As Espada explained to DigBoston, “We stood beside them in court, speaking for them. The hatred directed at them was intense. Some of it rubbed off on us. We didn’t, of course, encounter the same hatred to the same degree, but you can imagine how we were received.” He added, “I was standing before a judge one day when the mother of a landlord slugged a student representing a tenant.”

In the cab, the back-and-forth does not escalate into violence, but things do get more heated. The subject turns to the infamous Charles Stuart murder case of 1989, in which Stuart killed his pregnant wife, Carol DiMaiti Stuart, then blamed her death on an imaginary Black carjacker, sparking a police manhunt for a suspect that did not exist. After his brother turned him in, Stuart jumped off the bridge of the poem’s title—the bridge referenced in the poem by the increasingly agitated cabbie.

“In my poem, these stories [of being a tenant lawyer and the Stuart case] converged; the common denominator became the legal system and the violence against both the African-American and Latino immigrant communities perpetuated by that system,” Espada said.

The poem “Not for Him the Fiery Lake of the False Prophet” recalls a recent hate crime—the 2016 assault on immigrant Guillermo Rodríguez by the Leader brothers, Scott and Steve, outside the JFK Red Line MBTA station. The poem quotes Scott Leader as saying “Donald Trump was right. All these illegals need to be deported,” and it also quotes Trump’s rhetoric against Mexican immigrants, as it details the brothers’ gruesome attack on Rodríguez, urinating on him before beating and kicking him.

And yet, Espada reminds us, there are always those willing to show compassion in the face of cruelty, including the bystanders who called 911 after the attack on Rodriguez and the medical staff who cared for him in a hospital.

“In the end, that night there were more helping hands than hurting hands laid upon the body of Guillermo Rodríguez,” Espada said. “We are Donald Trump’s worst nightmare when we act from a place of empathy.”

Through it all, Espada knows he—and the nation’s poets in general—have to keep writing.

“I would say that more poems are being written, published, read and heard today than ever before,” he said. Yet, he warned, “Poetry gets lost in the swirl of the very same events that obliterate everything else.”

bookshop.org/books/floaters-poems/9780393541038

Rich Tenorio is a writer and editor whose work has appeared in international, national, regional and local media outlets. He is a graduate of Harvard College and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. He is also a cartoonist.