“Clean your hands, social distancing, quarantine, all those things were tried in 1918.”

History will show that the pandemic derailed the 2020 baseball season for the Boston Red Sox. Playing in empty stadiums, the Sox lost six of their first 22 games, putting them in last place in the American League East. Star pitcher Eduardo Rodriguez is out for the season after contracting COVID-19, and so the story goes.

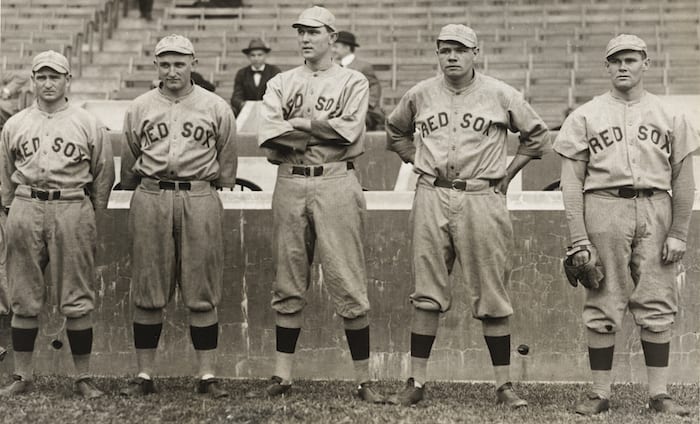

More than 100 years ago, the team also played ball during a pandemic. In 1918, Babe Ruth led the Red Sox to a World Series championship, all while off the field contending with the Spanish flu outbreak that terrorized much of the world. A new book, War Fever: Boston, Baseball, and America in the Shadow of the Great War by Randy Roberts and Johnny Smith, chronicles this uncannily similar moment.

Roberts and Smith are both professors—Roberts at Purdue University, Smith at Georgia Tech. They have collaborated on projects before, including one on the friendship between Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X. In a phone interview, Roberts said that the authors “had no idea” that when War Fever was released in late March, it would come out during another flu pandemic.

“A number of people who wrote articles on the book said it had incredible timing,” Roberts said. “I think the book is very relevant today.”

War Fever evokes the horrors of the Spanish flu, including in Boston, where the dead were stacked on city streets. Overall, it killed 675,000 Americans—Roberts described it as “probably” the worst pandemic in US history.

War Fever evokes the horrors of the Spanish flu, including in Boston, where the dead were stacked on city streets. Overall, it killed 675,000 Americans—Roberts described it as “probably” the worst pandemic in US history.

“People turned black, purple almost,” he said. “They died from lack of oxygen. It was really extreme, how terrible and awful their death was. It was pretty shocking to read about.”

As Roberts explained, people had the same questions about both the Spanish flu and COVID-19—Where does it come from? What can we do? How do we prevent it? Public health authorities, meanwhile, utilized identical measures.

“Clean your hands, social distancing, quarantine, all those things were tried in 1918,” he said. “And ‘how fast do we come back’ in 1918. It was a little bit too fast. [The flu] came again in early 1919.”

This summer, the recent restart to pro baseball has made the book even more relevant.

“It’s completely understandable that players are ready to play again,” Roberts said. “Certainly businesses are ready to get geared-up again. The jury’s out on what’s going to happen.”

What happened in 1918 was that “the flu really struck during the World Series, and so baseball had a number of months, from Sept 1918 until spring 1919, before it started up again,” Roberts said. “By that time, the flu pretty much ran its course in America.”

Even players like Ruth came down with the flu—in his case, twice, in what could only be described as an improbable year for the Great Bambino.

“We wanted to say something new about Babe Ruth,” Roberts said. “We wanted to look at the impact of the war on Babe Ruth’s life—not only the fact he got the flu several times, but how important the war was creating Babe Ruth the batter.”

Ruth is one of three Bostonians who are protagonists in the book’s real-life drama, which Roberts described as how the war affected everyday life in multifaceted ways, shown through the lens of celebrity. The slugger’s fellow main characters are Charles Whittlesey, a bespectacled Harvard Law graduate who became an unlikely World War I hero in occupied France, and Karl Muck, the German-born conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra who ran afoul of wartime bigots and landed in an internment camp. As you might expect, and without giving too much away, all three had dramatically different fates.

“One celebrity was really made by the war, one was destroyed by the war, another was made and destroyed by the war, in a sense,” Roberts said.

Noting the relative obscurity of Whittlesey and Muck among readers today, Roberts said, “Everybody’s heard of Babe Ruth,” including “[anybody] who knows anything about sports.”

Boston fans are a little too familiar with Ruth because of an infamous transaction between the Red Sox and the Yankees. Ruth and the Sox won the World Series in 1918, but the emerging home-run hitter played just one more season in Boston before team owner Harry Frazee sold him off to New York. The Sultan of Swat ignited the Yankee dynasty while his old team fell under the Curse of the Bambino. Yankees fans delighted in pointing out the reversal of fortune with chants of “1918.” Boston would not win another World Series championship for 86 years.

The book offers a perspective on Ruth that readers might not be familiar with. Before he became arguably the game’s greatest hitting star with the Yankees, he was a top pitcher for the Red Sox—setting a record for scoreless innings in the World Series that stood for decades. As the book explains, Ruth transitioned from pitching to hitting because of the war. After president Woodrow Wilson declared war in 1917, pro baseball faced uncertainty over whether it would continue as the country mobilized its resources for conflict.

Owners appealed to patriotic sentiments, playing the Star-Spangled Banner before games and having ballplayers participate in pregame military drills. Some players joined the military, leaving Sox manager Ed Barrow short of hitters. A solution lay close at hand, although at first Barrow didn’t want to lose Ruth’s prowess on the mound.

“His manager did not want him to hit, but to pitch,” Roberts said. “It was a struggle, a daily struggle, as 1918 [went] on.”

In time, Ruth not only got a chance to hit, he co-led the American League in home runs with 11.

“1918 was a transition year for baseball,” Roberts noted. “In 1919 [Ruth] was primarily a hitter over all that year. If not for the war, he would have probably remained a pitcher.”

In another transformation, the war made Harvard Law grad Whittlesey into a military hero. A scion of a prominent New England family, Whittlesey was working on Wall Street before joining the army. Because of a leadership shortage, superiors transferred him from a staff position to frontline duty during the 1918 Meuse-Argonne Offensive—“the greatest American offensive of World War I,” said Roberts, whose research included visiting the dense Argonne Forest where the offensive took place.

There, the bookish Whittlesey earned fame as leader of the Lost Battalion, a collection of military units that found itself isolated behind enemy lines during the offensive. For nearly a week, its members endured death and disease while fighting off German attacks. When Whittlesey received a request to surrender, he did not respond. A reporter who had not been there credited him with a pungent answer: “Go to hell!”

“He became ‘Go-to-Hell Whittlesey,’” Roberts said. “It was a phrase used, like ‘Remember the Maine, to hell with Spain,’ or ‘Remember the Alamo’—one of those short, pithy statements.”

Of the three-word response, Roberts reflected, “He probably never said it,” yet it gave him “a fame he never really wanted and never could escape.”

Inescapable fame of a different sort came to BSO conductor Muck. According to the book, his troubles began following accusations that he refused to play the Star-Spangled Banner when the orchestra traveled to Providence for a concert. Eventually, he drew the attention of the Bureau of Investigation—the forerunner of the FBI. Authorities learned that the married conductor was having an affair with soprano Rosamond Young.

Accessing their correspondence and suspecting him of espionage for the kaiser, they arrested Muck and interned him with fellow German-Americans at Camp Oglethorpe in Georgia.

Muck was not an American citizen, and had “a certain loyalty to Germany and negative opinions on many Americans,” Roberts said. “Is he a sympathetic character? Probably not. Did he deserve to be taken into a detention camp for the war? No.” According to Roberts, Muck was “probably not guilty of anything.”

For Roberts, Muck’s story shows that “here was America fighting the war, and also practicing repression at home.” He attributes Muck’s fate to the “hysteria of war,” adding, “This kind of story about Muck epitomizes what it was like to be ‘the other,’ a German in America during that time … just like in World War II with the internment of Japanese-Americans.”

Overall, Roberts said, America in 1918 experienced “huge inequalities,” including against labor and Blacks, with many of those inequalities having parallels today.

And as for the Spanish flu, it has a vital, forgotten legacy of its own.

“I don’t think most Americans are really aware of the Spanish flu,” Roberts said. “Maybe they’ve heard the term, but they don’t know how bad it was. Historical memory of those events has faded. It’s revived, of course, during the current pandemic, but it’s faded just how bad it was.”

War Fever: Boston, Baseball, and America in the Shadow of the Great War (Basic Books, 2020) by Randy Roberts and Johnny Smith is available wherever books are sold.

Rich Tenorio is a writer and editor whose work has appeared in international, national, regional and local media outlets. He is a graduate of Harvard College and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. He is also a cartoonist.