It’s been said at least once that the ’60s were really just ’66 and early ’67. And down similar lines we’ll always know that despite what the calendars might say, the year 2020 didn’t really start until March. Only then did it really become the year we’ll remember it as: The year without—or, for the purposes of this article, the year without movies.

The year where a seemingly endless multitude of so-called at-home equivalents replaced long-delayed theatrical lineups from major studios and independent distributors alike, and supplanted the standard moviegoing experience of sticky folding seats and big dirty screens. And in turn the year that inundated us with “virtual cinemas” hosted on hundreds of exhibitor’s webpages, and countless new strands of pay-per-view VOD offerings, and monthly announcements of new subscription-based streaming services, and so on ad infinitum… an endless rush of content with nowhere to present itself beyond the lonely privacy of your own home—real Twilight Zone shit.

With all that in mind: what purposes could a traditional year-end article possibly serve? Thus rather than asking Dig‘s film-section critics for top 10s, or best pictures, or anything like that, we simply asked what moving-image experiences they were most engaged by despite everything outside the screens working against them.

And they provided answers that only strengthened my own suspicion that the defining moving-image works of 2020 were not the sort of thing we’d traditionally call new release movies: for indeed, among the 11 selections listed below, you’ll find not only films but also two made-for-TV miniseries, a virtual play, a wrestling match, a YouTube movie, a Twitch stream… all these forms of screen-based moving images that now, once and for all, for better or for worse, richer or poorer, in sickness rather than in health, have achieved some kind of equality with their big-screen feature-length brethren. —Jake Mulligan

First Cow (2020)

Released to theaters on March 6th, pulled from theaters on March 16th, released to digital platforms on July 10th.

First Cow, with its unlikely friendships and heist plot and cute animals, would make for a charming story regardless of who was behind the camera. But director Kelly Reichardt doesn’t make charming stories—she makes observational, thematically rich, and visually controlled films that manage to untangle entire American myths in under two hours. First Cow is no exception. Here Reichardt’s fundamental interest in kinship in the face of capitalism is baked into each part of the film: The bond between Cookie, a meek indentured servant from Boston, and King Lu, a Chinese immigrant on the run, is as tender and personal as it is critical to each man’s survival in the great Oregon wilderness. Composing in a boxy aspect ratio, Reichardt rejects the sweeping widescreen vistas of westerns and instead focuses in on the intimate and the domestic—Cookie and King Lu treading through the woods or sweeping dirt from their makeshift home. The pair’s fate may be telegraphed from the start, but Reichardt’s purity of vision and commitment to lean storytelling maintains the urgency and importance of every last shot. —Cassidy Olsen

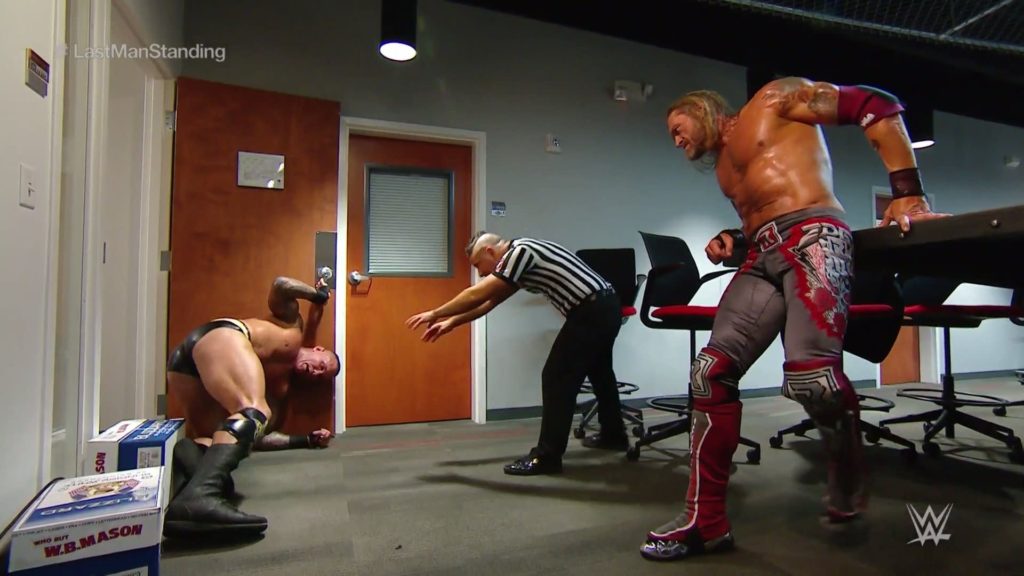

Wrestlemania 36: Edge vs. Randy Orton

Aired on WWE Network on April 5th.

When it was announced that 2020’s Wrestlemania would go on, despite every other professional sports league being fully shut down, it seemed to confirm the stereotype of the WWE as, well, stupid—representative of, and pitched to, the lowest common denominator of American society. But jump ahead a few months, and suddenly WWE wasn’t alone in callously refusing to put the safety of their workers ahead of their bottom line, with both the NBA and MLB (and later the NFL) resuming their seasons largely without fans. And so the crowdless Wrestlemania began to feel less like an anomalous decision by a crass, illegitimate industry moving to protect profits, and more like a predictor of where the country as a whole was headed: toward a full-scale denial of the gravity of the pandemic, an attempt to return to normalcy despite the blatant, unavoidable abnormality of it all.

The showdown between recently unretired Edge and his former tag partner-turned-heel Randy Orton was not the most creative or unusual match of Wrestlemania 2020 (that honor would belong to either of the two prerecorded and more significantly edited contests, which firmly established an oft-used post-COVID approach that viewers have begun referring to as cinematic matches). But it was the most grueling and intensely physical, a fact made all the more clear by the lack of a fan presence—allowing viewers to hear every hit, every body slam, even the superstars’ panting. It felt like an exorcism not only of the recently developed animus between the two wrestlers, but also of the tense relationship between the athletes and their employers. As the match made its way backstage, Edge and Randy wreaked havoc upon the whole of WWE’s “Performance Center,” from training rooms to administrative offices, as if fighting not only each other but the entire edifice of pro wrestling. Why do these people continue to punish themselves, pushing their bodies to the limit for a predetermined outcome, while serving an organization that has no interest in their well-being? The answer can be found in Edge’s face at the end of the match, basking in the glory of winning, of reestablishing his power as a performer and star. Is that feeling any different than what the Dodgers experienced rushing the field to celebrate winning a World Series, even after one of their players had tested positive for COVID midgame? It’s the Faustian bargain of sports, deeply illogical, and deeply American. —Etan Weisfogel

Normal People (2020)

Released on Hulu on April 29th.

Connell Waldron, one half of Sally Rooney’s Normal People, is a handsome, quiet, and deeply anxious kid from Sligo who studies at Trinity and plays Gaelic football. Paul Mescal, who shot to prominence this year for his turn as Connell in the BBC/Hulu adaptation of Rooney’s novel, is a handsome, quiet actor from Kildare who studied at Trinity and had to give up Gaelic football after getting his jaw broken. The match of actor to material is remarkable—but it obfuscates the immense craft Mescal brings to his first-ever screen performance. Playing against co-star Daisy Edgar-Jones, Mescal carries all five and a half hours of the intense romantic drama with startling emotional clarity. And even when it feels like director Lenny Abrahamson has placed one too many close-ups on the actor’s face—eyes heavy, mouth agape—Mescal doesn’t waste the space. He switches between subject and object throughout Normal People (a show that’s as much about power in sexual relationships as it is anything else), but even when the camera urges you to align with his partner Marianne, Mescal’s Connell is still who you sympathize with. So when years of silent worries come pouring out at a pivotal therapy scene late in the series, it’s hard not to feel his mixture of pain and relief: It’s the best depiction of anxiety I’ve ever seen on screen, and my favorite debut performance of the year. —Cassidy Olsen

I May Destroy You (2020)

12 episodes aired on HBO from June 7th through August 24th.

This is just one more drop in the immense bucket of praise Michaela Coel has received this year, but if it puts even one newcomer onto her considerable talents it’ll be worth it. She wrote, directed, executive produced, and starred in I May Destroy You, a 12-episode miniseries that follows the aftermath of a sexual assault: It is harrowing, candid and, astonishingly, hilarious. The trick to tackling such a sadly familiar situation, it turns out, is to be as truthful as possible—that is, to laugh and laugh until it stops being funny. Until you look around—or look inside—and realize the ways consent is continuously betrayed. Until you realize just how easy it is to be complicit in terrible behaviors, and how tenuous the lines are between right and wrong, true and false. So just as there are moments of incredible wit and humor, there are moments of terrifying insight and catharsis that leave your jaw on the floor until you’re ready to discuss—and discuss you must—with the nearest viewer. Coel does not shy away from truly disturbing explorations… but why would she? And why should she settle for a somber, self-serious tone when there is comedy to be found? I May Destroy You is Coel’s story to tell, and she does so beautifully. —Juan A. Ramirez

The Green Years (1963) and Change of Life (1966)

Released on virtual cinema platforms on August 7th and August 14th, respectively (now available here and here).

Scrolling Twitter sometime in early August, I came across an intriguing quote from Pedro Costa, director of this year’s formidable Vitalina Varela, from a 1997 interview conducted by authors Anabela Moutinho and Maria da Graça Lobo. Recalling his first encounter with the films of António Reis, Costa said, “I obviously remembered Isabel Ruth, who I consider a type of Portuguese Anna Karina, the most beautiful girl in Portuguese cinema.” Thirst traps are as good a pretext for cinematic discovery as anything else, so if you’re like me, for whom Karina was a major crush item in the salad days of my cinephilia, your ears have probably perked up. The occasion for Ruth’s mention on social media was the restoration and online presentation of two Cinema Novo films in which the actress stars: The Green Years and the Reis-co-scripted Change of Life, both directed by Paulo Rocha. In the former, Ruth plays the flighty love interest of a morose country boy (Rui Gomes) kicking around Lisbon, while the latter sees her inject ideas of rebellion into the mind of a troubled former soldier (Geraldo Del Rey), and in both Ruth is superb, concealing a roiling inner life beneath a visage of pained neutrality. Hypnotically paced and immaculately composed in black and white, both films emanate a haunting sense of displacement and troubled class consciousness, touching on the tensions between urban and provincial life, and the hardships facing the proletariat in postwar Portugal. For Rocha, a 14-year drought in feature filmmaking followed this striking one-two punch, at which point the director embraced color and magical realism, but in these largely unheralded calling cards he produced works of stark beauty that deserve mention alongside the great creative dam bursts of the French New Wave. —Carson Lund

Build the Wall (2020)

Released on Youtube on August 28th (now available on Vimeo).

Build the Wall is mumblecore pioneer Joe Swanberg’s return to no-budget filmmaking following a brief detour into the more commercial side of indie cinema with star vehicles like Digging for Fire (2015) and Netflix show Easy (2016-19). A small-scale character piece shot at actor Kent Osborne’s secluded Vermont home, the film feels paradigmatic of what has become the post-COVID filmmaking model—one location, a few actors, minimal crew—despite having been shot in August 2019, well before the pandemic began (Swanberg has often found himself ahead of the industry curve, but never before in such a weirdly prescient manner).

The plot involves Kent preparing for his 50th birthday by inviting potential love interest Jane Adams to his place in the woods; however, his friend Kev arrives first, unannounced, with a plan to build him a stone wall. Swanberg largely avoids the expected comic beats one might assume such a concept would inspire—like a scene of romantic bliss interrupted at just the wrong moment by Kev’s undertaking—and instead uses the parallel storylines to create a building sense of dread based around Kent’s anxieties about aging. But one can also read the two threads as representing Swanberg’s two sides as a filmmaker: one side interested in traditional dramatic concerns (love, the difficulty of human relationships, that sort of thing) and the other content with a kind of pure naturalism, human behavior presented devoid of conflict. The film’s conclusion feels like a moment of liberation for both Kent, who gives in to the joy of the wall-building project and seems to accept his milestone birthday, and for Swanberg, who eschews narrative resolution in favor of a beautifully observed scene of communal celebration. —Etan Weisfogel

Ghost Tropic (2020)

Released on virtual cinema platforms on August 28th (still available via theaters listed here).

Set in Brussels, Bas Devos’s Ghost Tropic is a movie that may nevertheless remind you of traipsing around nocturnal Boston during this time of year. In a meditative sequence that produces the film’s inciting incident, an aging mother named Khadija (Saadia Bentaïeb) drifts off to sleep on a train that bears a conspicuous resemblance to the Orange Line, then awakes in some outer borough to find that all trains have parked for the night. The ensuing cross-town journey home by foot has the feel of a Forest Hills-to-Downtown Crossing pilgrimage, at least in terms of increasing architectural scale and nightwalker population density, so if you’ve ever embarked on such a thing the film strikes a relatable chord, for better or worse, as Khadija takes in the recontextualized banality of her surroundings, wears her feet down, and frets over the well-being of sidewalk sleepers. But Devos’s unassuming third feature—shot in glowing 16mm and with ethereal tracking shots—is far more than a little night music to jog your memory. As the director steers Khadija toward a series of unlikely encounters and vaguely mystical happenings, this small episode of quotidian inconvenience becomes a moving portrait of a city’s flipside, the side most of us never see because we’re sleeping. It’s in this nether zone, Devos suggests, that humanity is most apparent. —Carson Lund

“Jerry Lewis Telethon Marathon”

Livestreamed on Twitch via Museum of Home Video on September 6th.

Though it’s not quite equivalent to the theatrical experience, the (hopefully temporary) cultural shift to virtual viewing has allowed for a certain amount of experimentation in streaming-based distribution. One of the most continually rewarding examples of that is the Museum of Home Video, a weekly Twitch show dedicated to found footage and archival ephemera: The museum’s programs capture that feeling of stumbling upon something utterly strange on your television at 3 am—a contextless and bleary-eyed stream of often absurd images selected with scholarly precision. And in turn a true highlight of my media viewing this year, streamed or otherwise, was the museum’s annual tribute to a baffling obelisk of broadcast television: the Jerry Lewis MDA Labor Day telethon. In the history of television, maybe moving images entirely, there’s very little else like the telethon—hours upon hours over decades of pure content devoted to, yes, a philanthropic cause, but also the outsized personality of one outrageous, uncontrollable man. There’s an absurd pleasure to be found in Lewis’ endless vaudevillian menagerie of child performers, Neil Diamond impersonators, and pop stars from the Osmonds to Oingo Boingo, but the main attraction is the ladies’ man himself, a frenzied force of nature and amphetamines in the form of mortal flesh. The telethon gave the comic live wire an endless platform to say basically anything he wanted, which often resulted in Lewis insulting and verbally assaulting anyone unfortunate enough to be within spitting radius. The duration of the telethons, as well as the unpredictability of Lewis’ performance style, lends them a surreal tedium that’s surprisingly enthralling—whenever your attention begins to drift, Lewis explodes in a fit of screeches and sweat, shaking you right back to attention. —Nadine Smith

This Is Paris (2020)

Released on Youtube on September 14th.

Like so much pop culture from the Bush years that was once considered lowbrow ephemera or even just a punchline, Paris Hilton has recently undergone serious reconsideration. And while Alexandra Dean’s documentary portrait of the celebrity maudit might come with the sanction and official approval of the highly image-conscious Hilton brand, it’s nonetheless shockingly revealing, a raw investigation of the intersections between the multiple selves and personas that Paris has marketed to the world. The film presents how Paris flips between two voices as a metaphor for her identity: There’s the iconic, hyperfemme vocal fry associated with the devil-may-care, dead-eyed party girl she played on The Simple Life (2003-07) and in the tabloid press, and then also the deeper, more casual intonation she uses in her personal life. In turn the film is also, in many ways, a coming-out movie, with Paris opening up for the first time—to her own family, to the public at large, as well as to an entire community of other survivors—about her experiences of trauma and abuse, specifically her time spent at a horrific “reform school” for girls in Utah while a teenager. This Is Paris is still, from one viewpoint, a glossy and sanitized product, as much as the eternal ingénue’s skin care line or custom holographic phone cases. But it’s more wounded and honest than anything she’s ever sold before, capturing Paris in moments of unmanufactured crisis: The scene where she’s about to play a set at an EDM festival and her German boyfriend descends into a state of aggressive drunken douchebaggery is maybe the scariest moment I’ve experienced in a movie this year. —Nadine Smith

Dick Johnson Is Dead

Released on Netflix on October 2nd.

In 2016 cinematographer Kirsten Johnson directed Cameraperson, one of the great American films of this generation. Presenting a series of scenes, B-roll footage, and clips from her other productions, it suggested entire philosophies and emotional movements simply by depicting preexisting scenes and then counterpointing them with others—a truly structural cinema. So when in 2017 Johnson described her next film, Dick Johnson Is Dead, by saying “another hybrid project, an observational documentary which I hope will be an hilarious heartbreaker… You know Groundhog Day, Buster Keaton, Jacques Tati, and Jackass? That will be the spirit of it… Before I lose my dad, I want to keep him for the future,” I got a certain kind of image in my head: imagining another film that makes daring formal use of disconnected interstitial segments, much like Cameraperson and Tati movies and the Jackass series before it.

In the actual finished movie released this year, Johnson works alongside her psychiatrist father—the titular Dick—to stages “death scenes” for Dad, like an air conditioner falling on his head during a stroll down the street. But after the first couple, Dick starts to weaken, and his daughter-director begins detecting the early signs of Alzheimer’s—to which they’d lost Dick’s wife and Kirsten’s mother a few years prior. And so the film they planned to make—mostly comprising “hilarious heartbreaker” scenes of Dick getting killed—instead becomes a movie about them trying to make the film they’d planned to make—mostly showing footage that depicts the behind-the-scenes production of their stunts more than the actual stunts themselves, as well as other scenes that work to reveal the shaky foundations of consent and collaboration that a “performer” like Dick necessarily gets caught up in on a project like this. Therefore replacing the exact framing and rigorous cutting of Cameraperson with the shaky images and smeary design of first-person diary cinema, Dick Johnson Is Dead is not the follow-up anyone could’ve expected, but it’s all the more revealing for it: not a truly structural cinema, but a truly personal one. —Jake Mulligan

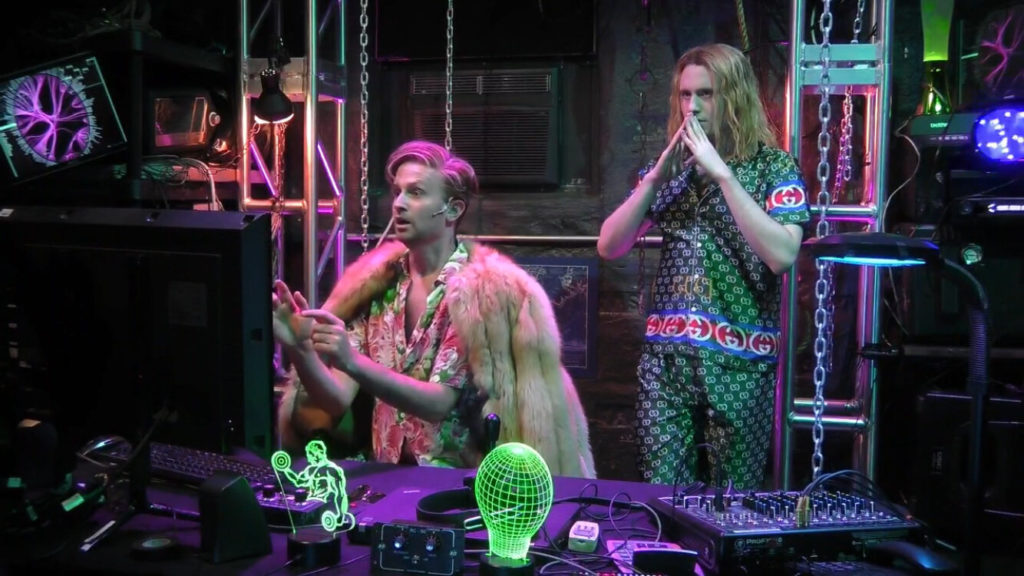

Circle Jerk

Livestreamed on circlejerk.live from October 18th through November 4th.

Pity the historians or monolith-planting aliens or Illuminati reptilians who come across a copy of Circle Jerk in a thousand years and are tasked with figuring out what it is. Hell, ask most Gen Xers what it means and they’ll probably run away in helpless defeat. The genius—and it is genius—of this live theatre-film-experiment can most likely only be appreciated if you’ve spent the last decade of your life doomscrolling on Twitter (or, God forbid, 4chan), but it stands as a monument to the highs and lows of internet culture. So what is it? An extremely online retelling of the Faust myth, I think. Or maybe Frankenstein. But mostly, it’s a scathing takedown of white gay culture that was performed live nightly for a week in October. Four actors swap roles, sets, and media to bring us the story of how an alt-right troll, his influencer friend, their incel housekeeper, and their Catholic houseguest team up to create the perfect data-driven AI meme machine. Clocking in at roughly 18,000 jokes and pop culture references per minute, it is the perfect encapsulation of 2020: hard to explain, mostly virtual, and fucking unhinged. —Juan A. Ramirez

Dig Staff means this article was a collaborative effort. Teamwork, as we like to call it.