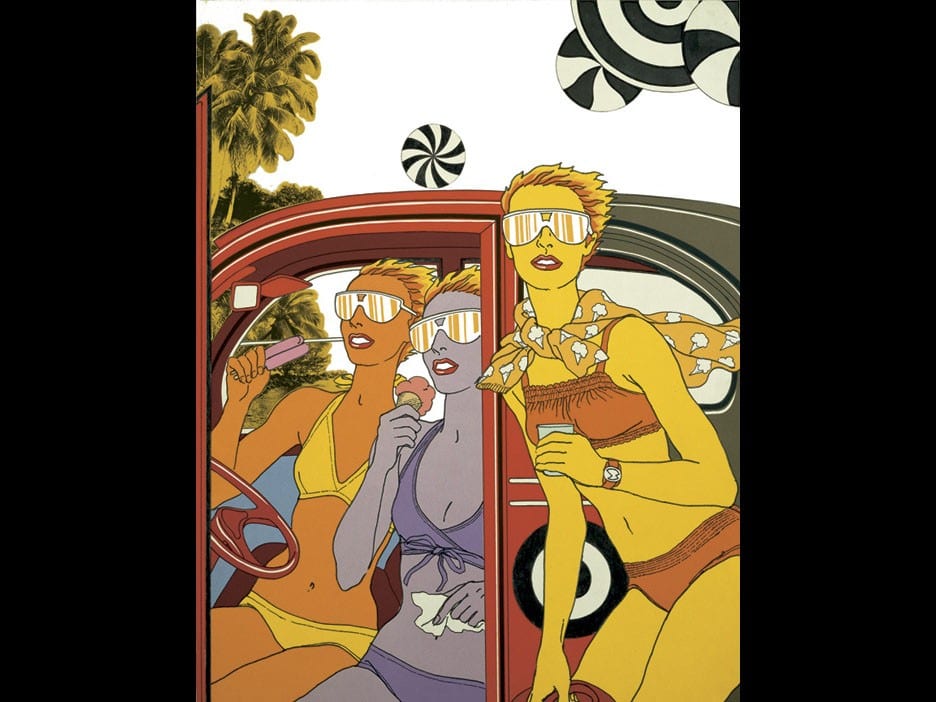

As a recently christened aficionado of renowned fashion illustrator Antonio Lopez, it’s hard for me to comprehend that, about five years ago, his legacy nearly passed me by. I remember stopping in front of the M.A.C. Cosmetics shop, in Soho, to look at the window advert for their latest capsule collection, “Antonio’s Girls”. And I recall smiling, as it was refreshing to see three noticeably middle-aged models—I knew the one in the middle to be Jerry Hall, and much later, learned the other two were Marisa Berenson and Pat Cleveland—freeze-framed in dance, and wearing vibrant maxi bodycon dresses. Inside the shop, I saw that the packaging for “Antonio’s Girls” featured selected illustrations by an artist named Antonio Lopez, originally done in the 1980s. I thought they were so cute, bold, and detailed. They reminded me of Jem and the Holograms. But I didn’t make a purchase, on that day or any other, from the collection. Looking back, I believe I wanted more out of the color stories in the makeup. I was 26 years old, the same number of years that had passed since Lopez had died from AIDS at the age of 44 in 1987, although I wasn’t aware of that back in 2013.

Lopez’s creative spirit would find me again in 2018. This time around I encountered his beautiful illustrations and transgressive artwork—along with various details about his career and personal life—through director James Crump’s new film Antonio Lopez 1970: Sex Fashion & Disco [2018]. The film, in turn, led me to further research on Lopez—and indeed there are a small handful of critical sources published, like the 2012 tome Antonio Lopez: Fashion, Art, Sex & Disco, or the notes from a 2016 Museo del Barrio exhibit on his work, ANTONIO LOPEZ: Future Funk Fashion. Yet despite these studies and exhibitions, I often found myself thinking that Lopez and his talent were still undervalued in the dialogue about 20th-century fashion. (Alongside his immeasurable contributions in fashion and pop culture as an illustrator and visionary, he’s also credited with bringing to the forefront various women who would later become iconic in their own right, such as Hall, Cleveland, Grace Jones, actress Jessica Lange, and Carol LaBrie, who was the first Black woman to cover VOGUE Italia). I was also surprised that Lopez, as a Latinx bisexual man, working right at the dawn of the gay rights movement, had been minimally discussed by modern LGBTQ and sex-positive media, as queerness was not excluded from his creations.

“That he was initially overlooked has a lot to do with the rush of energy he gave to illustration, and at a time, the field was nearing its last gasp, succumbing to the dominance of lens-based imagery and photography,” Crump said, via email. In answering my questions, the director showed a clear sense of duty to advocate for Lopez—he notes, for instance, that in terms of receiving posthumous reverence beyond their initial niche, Lopez has faced significantly more hurdles than contemporaries Guy Bourdin and Chris von Wangenheim. “As the film points out,” Crump continued, “Antonio was not simply an illustrator but also a stylist, and designer [and photographer], and therefore his work resists convenient labels or any simplistic art-historical [context]… Had his life not been cut so short by HIV/AIDS, I think he would be much better recognized and indeed he would be right at home in the art, fashion, and social media realms of today.”

Then what about Antonio Lopez, now that we’re reexamining sexual politics and agency, now that we’re humanizing our geniuses, and inclusivity in fashion and art are a subject at the foreground of national discussion? Antonio Lopez 1970 champions the artist—and his one-time romantic partner, lifelong artistic director, and fellow Nuyorican, the unsung Juan Eugene Ramos—as bellwethers of innovating fashion illustration. They are celebrated as radical stylists (Lopez drew by looking at real-life models in real time—“He rendered,” as fashion editor Joan Juliet Buck enunciated); as arbiters of trends and forecasting (Lopez was obsessed with taking suggestive Instamatics, prefacing controversial photo albums such as Madonna’s Sex [1992] and Kim Kardashian West’s Selfish [2015]); as individuals who encouraged the fashion elite to think towards the future and the now by their exaltation of iconoclastic beauty, by their support of youth culture and social uprisings in their late 1960s work, and by their exploration of what we may refer to as pansexuality. And the 1970s, the period which the film names itself after and emphasizes most, was the heyday of their kismet pairing.

The documentary developed as a passion project for Crump, once a rural Indiana youth who could be found admiring Lopez’s work in an issue of Andy Warhol’s Interview. As an adult in 1997, Crump met Paul Caranicas, heir and executor to The Estate of Antonio Lopez and Juan Ramos. He gave Crump unprecedented access to the archives, leading directly to 1970, which, like your average bio-doc, is buttressed by photos, interviews, and vintage clips (though there is scant footage of Lopez himself, even in Caranicas’ vault). Figures present to speak about Lopez and Ramos include Cleveland, Lange, Jane Forth, Donna Jordan, Patti D’Arbanville, writer and former Interview editor Bob Colacello, Grace Coddington, makeup artist Corey Tippin, and most wonderful of all, the late Bill Cunningham, a true national treasure seen here in his last on-camera interview.

The film is interested in the transformative early years of Lopez’s adult life (a general approach that has been heavily favored by nonfiction biopic filmmakers of late—Sara Driver went down a similar road with Boom for Real: The Late Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat [2018], as did Stephen Loveridge with his Matangi/Maya/M.I.A [2018]), in this case meaning the late 1960s through 1973. And given that focus, 1970 is joyous, vivid, and provocative. It follows Lopez from Fashion Institute of Technology wunderkind to prominent international fashion illustrator, luxuriating in the period of time when he and his coterie were Parisian expatriates collaborating with Karl Lagerfeld, while also making ample time for interviewees to ecstatically divulge about Lopez’s sexual magnetism. Given the upbeat tone of the piece, and the way it cites but doesn’t deep-dive into the social issues at the center of Lopez’s life story, at least a few critics have published reviews of the “I-enjoyed-the-film-but” variety (“The doc loses sight of its subject, and is almost over before it acknowledges the disease that would kill him”, wrote John DeFore in The Hollywood Reporter. “Despite all the acute detail and 70s flavour that we get in this one, it is oddly incurious about its subject’s inner life, content merely to re-state the legend”, per Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian). 1970 does speed through topics like the division between racist, elitist American fashion editors and the ostensibly more open-minded Europeans; Lopez’s fear of homophobia from his mother; and his heartbreaking last days, which are most effectively recounted by Caranicas, and by Cunningham, who breaks down in tears. But while I agree more time spent on Lopez’s last year would’ve been befitting, 1970 was designed to be a homecoming, not a requiem, for its subjects.

“Just because I think an element is important to include in my films doesn’t mean that is what the film is about, “ Crump noted. “AIDS, for example, is touched on in this film but the HIV/AIDS story itself has been told, many times and told very well,” he continued, citing his earlier film Black White + Grey: A Portrait of Sam Wagstaff and Robert Mapplethorpe [2007] as an example. “In many ways, this film is really about love. Antonio’s and Tina Chow’s bouts with AIDS are dealt with sensitively but in a manner that is commensurate with their total lives. They aren’t victimized by the darker sides of their reality but rather memorialized for who they really were as humans.”

More than anything else 1970 is nakedly transfixed with the bacchanalia of the times it depicts. Lopez’s close friends characterize him as a “sex addict”, not to mention an expert flirt, and his female muses (“partners in crime” according to Crump) breathlessly admit to having intense crushes on Lopez (or, in other cases, dalliances with him). In April 1973, he was featured in an Esquire profile, “Rags By Trade, Girls by Antonio”. The article—in which the writer Jean-Paul Goude coined the phrase “Antonio’s Girls”—makes a cameo in 1970, and is an invaluable resource on the artist.

“I changed [Pat Cleveland] from a sex symbol to this,” Lopez is quoted as saying. “I bring out what I think can be brought out, I never impose anything. But if women like you, they’ll do anything for you. They resent that at first, but in the end, they see I’m right.” Later in the article, another startling quote: “Women are insecure creatures when it comes to beauty, but a man knows. That’s why behind every woman there is a man—for example, Jackie Onassis, Valentino.”

These Lopez soundbites read like empty Svengali doozies. Yet his surviving “Girls” speak of him dreamily in 1970, so much so that I briefly pondered if Lopez was something of a calculated mastermind in his mentorship. Maybe even comparable to Prince, another nonpareil artist full of fervent sexual energy and crazy talent, who upheld women collaborators (Sheila E., Wendy & Lisa, Rosie Gaines) while also mandating a specific look and agenda for his proteges (Vanity, Jill Jones, Carmen Electra). I queried Crump about exactly that.

“Antonio possessed a near paranormal ability to see inside his subjects and identify traits that maybe she or he were unable to recognize in themselves”, the filmmaker offered. “He wasn’t content with Cleveland, for example, simply being a sexual object for the male gaze. Like all of the iconic models he worked with or discovered, he understood her talent and individuality. He certainly flirted with his female subjects but he did so in a manner that empowered them; he made them feel smart and appealing as individuals. We have to remember that the sexual revolution was in high gear when he hit his stride in the early 1970s and it was a far more open and experimental period of time.”

Let it be known: I’ve since righted my wrong of five years ago. I now carry with me, almost on the daily, the double-sided compact mirror from the M.A.C. “Antonio’s Girls” collection, which I bought from an online reseller this past spring. I’m in awe of this small bit of heaven from Lopez’s wonderland, covered in black velvet, with one side featuring an illustrated woman looking like the most glamorous punk ever drawn. Even if it took five years, I never stood a chance against the allure of his artwork. They are truly stunning. Crump is aware that most viewers will likely be new to Antonio Lopez, just as I was the first time I encountered “Antonio’s Girls”—which only gives him more reason to frame Lopez and Ramos as legends of illustration, who didn’t wait for an envelope to be delivered and pushed, and remained underdiscussed for far too long. Such envelopes, they imagined it and drew it and filled it with their own vision of how transcendent and revolutionary a drawing could be. Holding my “Antonio Girls” mirror in my hand, I think about just how lucky we are to have that work—to have had Antonio’s influence, for 44 years and beyond.

ANTONIO LOPEZ 1970: SEX FASHION & DISCO ENDS ITS RUN AT THE KENDALL SQUARE CINEMA TODAY (11.15), WITH SHOWINGS AT 2:05, 4:40, 7:20, AND 9:40. FOR MORE INFORMATION ON THE FILM AND FUTURE SCREENINGS, SEE SEXFASHIONDISCO.COM.

Shardae is a writer covering music, film, and arts in Greater Boston.