“Taking Action is Thinking, in an Academic Context”

In this second piece about the ongoing reflection process by Boston-area arts institutions in response to the Black Lives Matter movement, we’re meeting one of the people who spearheaded this whole conversation—in the context of where she makes a living, and where her professional evolution is occurring.

Though the Boston Arts for Black Lives open letter discussed in the first installment of this series was a piece of teamwork, and inspired by the teamwork of others in New York City and Philadelphia, Abigail Satinsky has been the most visible spokesperson for the group so far. The letter was devised outside of her capacity as curator of exhibitions and programs at Tufts University Art Galleries and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts, but signed by her within that capacity, and there’s no way to fully separate the drive behind the production of the letter from the environment that she was situated within while it was being produced—one where the majority of her coworkers were eager to sign it as well. Overall, the letter had 21 signers from the Tufts/SMFA community, including six of TUAG’s 11 staff members.

And it’s not the only written statement of commitments around these themes circulating in this community.

Launching an observance of Junetheenth as a day focused on “reflection, commitment and action,” Tufts’ President Anthony Monaco has made a statement outlining a series of “workstreams” that, in true academic fashion, emerged out of “14 breakout sessions and two plenaries.” It has resulted in the establishment of targeted working groups, the progress of which specific, named, senior-level administrators will be held accountable for.

TUAG also has a Statement of Commitment to Racial and Cultural Equity of its own, which Kaelynn Maloney, the department and curatorial assistant, reports was somewhat informed by Boston Arts for Black Lives’ work.

Many other Tufts University departments have made similar commitment statements, all of which can be found gathered together on the webpage of Tufts For Black Lives, a more ad hoc group formed by students, faculty, and staff across departments and outside of the top-down working groups mentioned above.

The point here is that if it’s true that where there is a will there is a way, since there is no lack of will at Tufts (and by extension, SMFA, which was incorporated into Tufts in 2016), there must be a way toward meaningful harm reduction. The problem is that—in comparison with the scale of the Boston Center for the Arts where that way is fairly straightforward—in a university setting, that way (or perhaps it is multiple ways?) is much more labyrinthine.

But the commitments in all of these statements are relatively concrete. The working groups target very specific issues like policing on campus, the impact of public art, land acknowledgement (institutional recognition of how their inhabiting particular physical places has involved violent displacement of indigenous communities and culture,) and the auditing of systems ranging from museum collection practices to community composition (at the student population and human resource levels.)

(Notably absent at the institutional level are any specific commitments around divestment, which is called for explicitly by Tufts for Black Lives. But notably present is a way to provide feedback/input alongside every statement.)

***

Tufts/SMFA’s art galleries, which like all area universities usually contribute significantly to the depth of Boston’s art community’s cultural life, are currently closed to the public due to the pandemic. So their staff is using this time of forced internal focus to clear pathways and make space for new practices.

Satinsky describes the unique nature of this time of both pandemic pause and national uprising as a kind of “portal” for imagining “new kinds of institutional futures.” It feels to her like a moment to step into that portal.

“If the conversation in the world is about abolition, and abolition is fundamentally about thinking about care and repair, then how can we imagine a set of provocations and things to struggle with, from where we are, that we could think about reorienting around?”

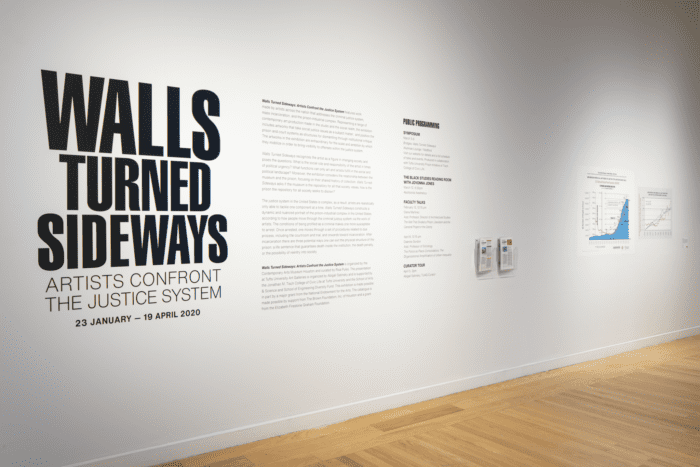

In terms of presenting art, this means going beyond simply showing political and “socially responsive” work, as TUAG has been doing, but figuring out how to create “more support and hospitality” around that work.

She dreams of “space for reflection,” intellectual space where “there is no right response to this work.” Presentation that fully acknowledges that we are all “approaching it from really different positions.”

Toward this end, Satinsky points to TUAG’s initiation of a new student advisory panel (paid student advisors who may also sit on university-wide committees as a part of their purview) to inform gallery programming going forward, giving students more “agency to talk back to us,” and describes the early stages of her own deep inquiry into best practices around land acknowledgement.

She seems to be thinking forward into the future and looking carefully into the deep past at the same time.

***

Dina Deitsch, director and chief curator of the Tufts University Art Galleries, describes TUAG’s current strategy for dismantling white supremacist culture as taking action in three stages—“the now-soon-later” approach, she calls it.

The question of what the “now” work looks like turns out to include a few more committees. Deitsch is alert to the irony of action taking the form of thinking. “The university is very into working groups. It’s the bureaucracy of university.”

But she sees the value in dividing things up this way, explaining that breaking things down “into categories that also followed people’s workflows” has allowed those in the university with different specialties to better apply them collectively to different kinds of problems.

Problems like removing, but also preserving for educational purposes, murals in the school’s heavily trafficked Alumnae Lounge, which inaccurately depicted the university’s history as an entirely white endeavor. Or doing a complete audit of the inclusivity of the school’s art collections.

Through these arts-driven committee projects, Deitsch sees the awakening of a deeper understanding at the school’s upper levels “that the visual environment and visual culture of the school matters. And it matters at a very visceral level.”

But Deitch also acknowledges that these “now” actions are only a beginning.

“Our programs have always been very diverse and thoughtful,” but this summer, she says, “I was hit like a ton of bricks with the back of house.” TUAG, she’s realized, “can’t separate our programming from our staffing and from how we communicate, and how we understand. These are not separate projects.”

And she describes a new sense of urgency.

“It’s not a background conversation anymore. It’s a front-and-center conversation. For us to shift our resources is actually not difficult programmatically at all. It’s very straightforward.” The sticking point is “the deeper resources, which is where staffing comes in.”

“Diversity of staff,” she admits, “is a huge issue for us. But it’s not something that we have capacity to manage right now, because we’re on a hiring freeze.” So she is focusing for now on “aspects of the gallery” where, she says, “we have immediate control over what we can do.”

***

Others on the TUAG team describe feeling empowered to focus on issues of equity and inclusion to a much higher degree than they have in the past, and they appreciate the pandemic’s disruption of business as usual because it’s giving them more time and space for this work.

Exhibitions coordinator Kaitlyn Ovett Clark, usually based at SMFA but now working virtually and more closely with her Tufts colleagues, sees the shift as one related to the scale of the conversation.

“I think it’s really easy in my day to day to just be kind of thinking about what I’m doing and how I’m moving things forward. And then, you know, a step up would be what the gallery staff is doing, and what the galleries are representing and then a step up is like what is SMFA doing?”

She says she feels like this moment has been “a chance to look at how can we change things as an institution? How can Tufts really make some major changes that it needs to? And then also, how can we work cross-institutionally? Boston is such a city of institutions, and we all collaborate in so many different ways. And since we’re such a college town, and institutional-based town, how can we use our strength and our power in that to make change by having these conversations with one another, instead of being isolated to our own campuses?”

Liz Canter, manager of academic programs at Tufts University Art Galleries, works directly with students and faculty to tie gallery programming to their curriculums and develop educational materials to accompany artwork.

“For me,” she explains, “it’s not necessarily new thinking. It’s just how to actually apply—take some of that thinking—and apply it and get the right people involved in the right places, and figure out what the next steps are.” Like Clark, her investigations of where to go next are informed in dialogue with her peers outside of Tufts, primarily at the national level, through the Association of Academic Museums and Galleries.

Though they are somewhat in a vacuum without being able to engage and get feedback on their efforts from a general public, TUAG’s staff is not just talking to one another, but also listening.

The team has had two trainings with Design Studio for Social Intervention, which Kaelynn Maloney says has helped her see keeping space open for continued conversation as a kind of action. “Judith and Kenny,” she says, “who are our facilitators for that training, provided the tools and the space for continued thinking and learning. I’m very indebted to them for providing those frameworks to us.”

Keeping space and conversation open is certainly an important piece of this work, so as this series offered last time, the conversation is open to you.

Have your recent interactions with Tufts/SMFA demonstrated the thoughtfulness these folks report putting into their work? What more are you hoping to see happen in the galleries, collections, public art and the visual (or general) culture of these environments when this series circles back a year or so from now to check in? This article invites comment, discussion and debate via Twitter @hkapplow.

Heather Kapplow is a Boston-based conceptual artist and writer.