With Boston’s major moment extended through July, a longer look at the impact of an iconic exhibition

Last year, Mattel released a beautiful $50 Barbie doll in a bespoke suit covered with his recognizable figures and skulls. His iconic artwork was also on Herschel backpacks, months before the release of a $795 “Empire” bag from Coach. And more affordable ways to wear his art can be found at superstores, where you can get a dinosaur tee for $20. Then there’s Yusaku Maezawa, who in 2017 paid $110.5 million for one of his 1982 paintings named “Untitled.” It remains the most expensive work by an American artist ever sold.

The “he” and his sometimes mass-produced oeuvre here is Jean-Michel Basquiat. In the 33 years (this August) since his passing, his name and art have graced covetable merch and the latter shown in popular exhibitions like Writing The Future: Basquiat and The Hip-Hop Generation, which has been extended through July 25 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Writing The Future is more than a humble brag for the MFA, as it is said to be the first mainstream museum exhibition to solely connect Basquiat with hip-hop as a subculture. (Break dancing! DJing! The music! Grassroot art shows and parties). With the extension of the show, they will continue hosting what’s been a sincere trip back to an era of art that’s felt so bygone for so long, yet that’s an evergreen source of inspiration.

For years, Basquiat himself has evoked research, intrigue, and incredible nostalgia alongside his artwork’s commercialization and supply and demand. He’s also become the unshakeable catalyst when discussing graffiti and street art’s allure, as well as its ongoing graduation to the big leagues of (often white-owned and curated) museums and auctions.

The elements

To rewind a bit, by 1985, Basquiat was the art darling of the media. But in his day, he was part of a remarkable coterie of New York City artists. In their work, they too had radically dissected city life and poverty, violence, and politics across social and gender/sexual lines, and some even recorded hip-hop tracks. And due to many of them being of Black and Latinx identity, recouped cultural lineage was also embedded in their performances and art.

These artists—Basquiat’s peers during graffiti’s initial domination, with the “bombing” of trains with loud, eye-catching tags and cartoons; and post-graffiti —are the MFA’s true focus. It’s during post-graffiti that street art began to be noticed as viable by (again, white) art world bigwigs and galleries. But besides Fab 5 Freddy and Keith Haring, most exhibited in Writing in Future are pretty unknown to the general public.

In a timeline that starts with a 1979 tagging of “FAB5” by Wild Style film star Lee Quinones and co-star Fab 5’s own 1980 “Campbell’s Soup,” and leaving us somewhere in 1989, 120 pieces and artworks by ERO, Kool Koor and LA2, to name a few, are displayed in Writing. Rightfully and finally, Basquiat’s friends are honored alongside him for this hip-hop reunion.

Writing The Future, curated by Liz Munsell and Greg Tate, was meant to open in spring 2020. No one could visit at the time due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and initially the MFA did its best to satiate future visitors with Instagram stories and talks with guests like Lupe Fiasco and Futura (aka Futura 2000, also featured in PBS’ vital documentary Style Wars). A few of Futura’s pieces are included in Writing, such as his continuous back-cover artwork brilliance across five separate ‘82 hip-hop LPs in the “Music” room.

Once October came around, the MFA re-opened its doors and then temporarily closed again from early December to mid-January due to the pandemic. With things back up and running, it has proven to be much more than just a typical exhibit. There’s The Mural Project, led by MFA artists-in-residence Rob Stull and Rob “Problak” Gibbs. And in April, in partnership with Boston Public Schools, the museum gave 160 free admission tickets to students, parents, and educators. This came after students were encouraged to enter a Basquiat Arts Challenge that asked them to respond to the prompt of: “Who inspires you as an artist?”

“The arts play a crucial role in fostering Boston’s economic, civic and cultural recovery while enriching and empowering the lives of our residents,” Mayor Kim Janey said in a statement after a Writing tour on April 6 from Munsell. “I am incredibly excited that the partnership between the [MFA] and [BPS] will provide our students with access to one of America’s most exceptional artists.”

Regarding Basquiat, the penultimate room—“Bodies”—warmly examines his years-long fascination with anatomy, thanks to his mother Matilde handing him Gray’s Anatomy as a youth in the hospital. The second room, “Portraiture,” features pieces that chronicle his take on living and creating art while Black. It’s not a newfangled concept to retrospectively study Basquiat as a provocateur, but credit should be given to Chaédria LaBouvier for ushering in a reappraisal of his art as activism.

Like Mayor Janey, who broke ground as the first Black person and first woman in a historically white male space, in 2019, LaBouvier curated for the Guggenheim, Defacement: The Untold Story. Its centerpiece was Basquiat’s “Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart),” a ‘83 painting made in tribute to Stewart, who died after being violently arrested and beaten by New York City Transit cops.

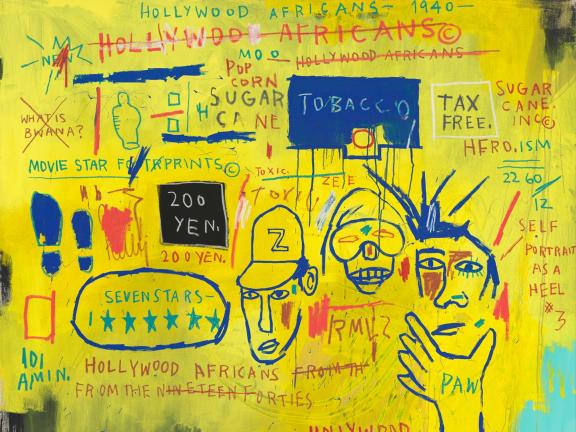

Reintroducing this work pushed the narrative of Basquiat beyond his pop culture icon status, regularly served on merch through slightly safer selections from his catalog and lyrical shoutouts from Jay Z, a member of the hip-hop generation after him. When in actuality, Basquiat regularly confronted racialized violence and nuances specific to Black and brown human life. In Writing, he’s again presented as an impassioned emblem in ‘82’s “Charles the First” and ‘83’s “Hollywood Africans.”

“Hollywood Africans” subtly confronts old Hollywood’s commodification and negative or often mediocre portrayals of Black people on film (four years later, director Robert Townsend would take the industry to task in his 1987 comedy, Hollywood Shuffle). “Charles the First” is an abridged bio of jazz great Charlie Parker, with Basquiat writing in the bottom left-hand corner, “Most young kings get their head cut off.” A statement made before the shocking death of Stewart stirred downtown New York, and in a similar vein to James Baldwin’s searing 1961 quote, “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a rage almost all the time.” It all upsettingly coincides with current reports of domestic terrorism, police brutality, and systematic racism towards Black people and people of color. Visitors may despondently ruminate on what has and hasn’t changed in America, as did Basquiat and his contemporaries in the graffiti age.

The contemporaries

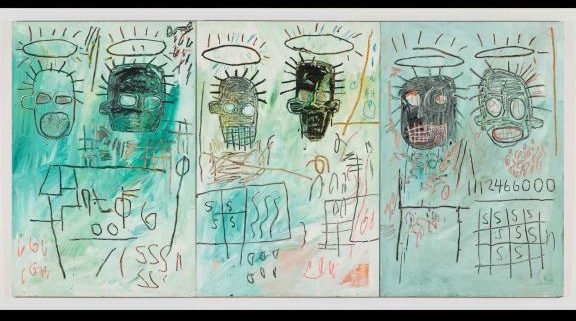

Basquiat’s friends Toxic and Rammellzee were captured as the other two heads (to the left of him) in “Hollywood Africans,” and both are featured throughout Writing. Rammellzee, who rapped memorable bars during Wild Style’s outro, is posthumously upheld as a Gothic Futuristic bellwether, theorist, fluid graffiti writer, and emcee; one place he shows up is on a rare original pressing of the ‘83 single “Beat Bop: Rammellzee Versus K-Rob,” with vinyl art by producer Basquiat in the “Music” room. “Futurism” is right after and largely dedicated to him with pieces like his intricate “Hell, the Finance Field Wars,” and a few personal items.

In the terrific sendoff, “Ascension,” the unexpected presence of his ‘89 multimedia, throwaway items assembled costume “Gash-O-Lear” (or “Gassolear”) stakes its claim as another standout gem finalist of Writing. Displayed in low light, Gash-O-Lear is an unforgettable gumbo of African folklore and Japanese samurai armor.

The costume elicits fascination and a little bit of shock. It is one of many alter egos with a costume Rammellzee created, and if you never did get to see him wear one live, it’s unfathomable how he got one on.

In later years, there have been greater efforts to promote his genius through showcases and auctions. A deeper dive also reveals that in comparison to Basquiat and Haring, Rammellzee’s complex vision was not as easily digestible or marketable. Eleven years since he’s died, it’s evident that it would have still been our loss if his canon was kept under wraps.

As far as women in Writing go, Jenny Holzer and Lady Pink are in the building. Holzer collaborated with A-One for the striking painting “Flashlight Text: Survival.” Above the somewhat disfigured outline of a human face, surrounded by graffiti, the devastating afterthought reads: “When someone beats you with a flashlight you make light shine in all directions.” With a date stamp of ‘83-84, if you know of Stewart’s death, you may think of him here. But even without knowledge of it, it is poignant.

Holzer also created “Tear Ducts Seem to be a Grief Provision” with Lady Pink, presented in “Bodies.” Lady Pink, who played Rose in Wild Style, is the treasured First Lady of Graffiti. At the age of 16, she was eternalized as “One of the few female writers to have earned respect,” as the Village Voice put it in ‘80. The Ecuadorian-born talent is still admired for her illustrative murals and vibrant renderings of women. MFA curators, however, went with a more sobering piece of hers for the “Writers” room.

Her ‘85 “Yellow Building,” meanwhile, displays as a classic graffiti piece. More time with it reveals a perturbed woman behind the bars of a decrepit bubble-lettered building and a stormy sky behind it. As the MFA explained, it’s commentary on urban decay with a feminist twist. Yet the doomsday vibe, with its obscured female lead, really transcends as a melancholy dictum on the victimization and survivalism of women.

The most collaborative piece in Writing the Future is the most indicative of the original hip-hop generation. In the first room “Post Graffiti,” the nicknamed “Fun Fridge” (‘82) is a faded yellow buttercream fridge marked by graffiti, tags, scribbles, and drawings by Basquiat, Dondi, ERO, Fab 5, Futura, Haring, Lady Pink, Rammellzee, LA2, Kenny Scharf, Tseng Kwong Chi, and others. Wholly chaotic and spontaneously made during artist visits and exhibitions at the Fun Gallery, it’s a precious relic of graffiti and post-graffiti because of who marked it. But also a tacit representation of camaraderie between these visionaries and how they diversified gallery art, and decades later, their influence on popular culture.

The most collaborative piece in Writing the Future is the most indicative of the original hip-hop generation. In the first room “Post Graffiti,” the nicknamed “Fun Fridge” (‘82) is a faded yellow buttercream fridge marked by graffiti, tags, scribbles, and drawings by Basquiat, Dondi, ERO, Fab 5, Futura, Haring, Lady Pink, Rammellzee, LA2, Kenny Scharf, Tseng Kwong Chi, and others. Wholly chaotic and spontaneously made during artist visits and exhibitions at the Fun Gallery, it’s a precious relic of graffiti and post-graffiti because of who marked it. But also a tacit representation of camaraderie between these visionaries and how they diversified gallery art, and decades later, their influence on popular culture.

Writing the Future wraps in a video montage outside the exhibition’s exit. In it, Bostonians share thoughts on how far the graffiti movement has come, and discuss the importance of a show primarily of Black and brown talent. All were moved, even relieved that such a significant moment had come. Now, hip-hop is a global wonder, Basquiat is a hero to many, and street art is a branch of contemporary art. Greg Tate did posit in his essay, “Black Like B.,“ ”What would have been the effect on Basquiat of a hip-hop culture as polyglot as himself?” We can only imagine.

Moving forward

You know the movie Wild Style by now thanks to its handful of mentions. In a scene before the finale, Quinones’ character Zoro, tasked with a mural for an outdoor concert, is chastised by Rose, after disclosing his frustration with finishing it.

“Zoro this. Zoro that. We don’t wanna hear about that. You’re only worried about Zoro. Concentrate on what the whole thing is about. The jam! Rappers are going to be coming down. They’re going to be the star of this thing. Not you!”

Treating Writing the Future as a jam was fortunately understood by the MFA. The draws of Writing were the magic words of Basquiat—the most iconic and merchandised. Goods await you in the gift shop—‘80s hip-hop and graffiti. But once immersed and from room to room, the takeaway is that the visual poetry of the streets, created with purpose, truths, and an ode to culture during a maddening time in NYC, were demonstrated before, during, and after Basquiat—and the revelation is okay. In fact, it’s needed. If the radiant child is the conduit to (re)discovering the other writings and paintings on the wall by sundry talents and collaborators, it’s a conscious move worth taking for the legacy and reach of post-graffiti. Writing the Future is a fitting epilogue for such a storied and bombastic time.

Shardae is a writer covering music, film, and arts in Greater Boston.