“Now here comes Miss Rona and fucks the whole thing up, because places can’t open at capacity.”

“The blues is the truth—I’m not just playing to entertain massa.”

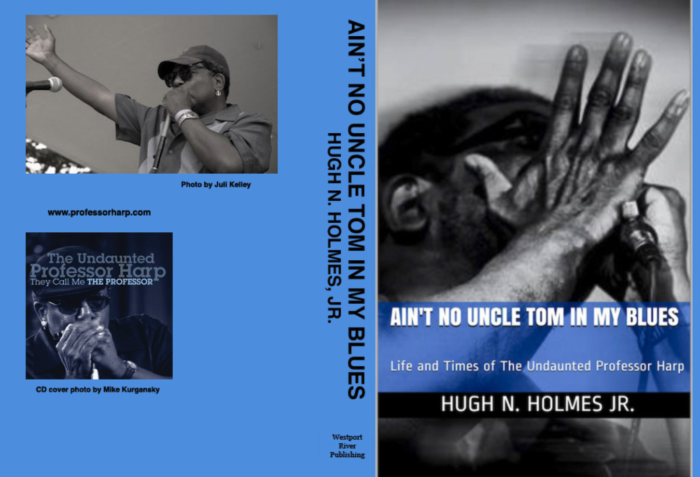

Hugh N. Holmes Jr, who has performed in Boston for decades as the Undaunted Professor Harp, brings a direct, unvarnished approach to the way he plays traditional blues on the harmonica—as well as to his unapologetic critiques of society and the contemporary blues world. Even by the standards of the low-profile Boston blues scene, Professor Harp is underrated, rarely scoring the kind of gigs or attention that would be warranted by an artist with his talent, longevity, and resume, which includes jamming with Muddy Waters and opening for B.B. King.

Holmes’ saga as a Black Boston blues lifer is chronicled in his new self-published memoir, Ain’t No Uncle Tom in My Blues, which details his childhood in Bridgewater, his introduction to blues via Boston rock in the early ’70s, and his life spent balancing a day job as a now-retired state social worker with the rough-and-tumble biker bars that Professor Harp can often be found in. While Holmes is unsparing in his grievances about racist or inept club owners, he also details the trouble he’s had keeping his own combo together, making the book an interesting look at the challenges faced by a local working bandleader.

Since the publication of the book, COVID-19 has further decimated local roots music venues, which were already facing gentrification and changing taste. One exception seems to be the Porch in Medford, whose pre-COVID booking policy was one of the area’s most inclusive ones. Professor Harp and his band play the Porch’s outdoor patio on Sept 5, his first gig in months.

“The scale hadn’t really improved for musicians in about 50 years,” says Holmes, who at 68 is still a generation younger than many of the other artists who make up the single-digit list of Black New England blues bandleaders, like octogenarians Shor’ty Billups, Luther “Guitar Junior” Johnson, and Toni Lynn Washington.

“Now here comes Miss Rona and fucks the whole thing up, because places can’t open at capacity,” he says. “It could take two or three years before everything recovers.”

Considering how Holmes keeps his Black identity front and center, it was surprising to learn that the first live blues act he saw was the J. Geils Band and its harmonica wizard Magic Dick at the legendary Boston Tea Party venue. Holmes is happy to praise white blues musicians—as long as they don’t try to turn the music into blues-rock or suck up the spotlight.

“Magic Dick learned from Little Walter,” says Holmes, referencing the iconic Chicago harp player. “Geils, they are bad boys, but the best way to know something is always to go back to the source.”

Asked point-black if a white Boston-based artist with the same talent and band would be garnering more praise and a busier tour schedule, Holmes doesn’t pause.

“Absolutely, because that’s who they push. We’ve seen that before with rock with Pat Boone, now it’s happening in hip-hop and R&B. They’ve always done that.”

On his disinterest in engaging in music business diplomacy, Holmes says, “I never had the patience to play games all that much. If you were too outspoken, back when I was a kid, it was a chip on your shoulder. They’d call you ‘divisive.’ But to be divisive you have to be united in the first place, and this country has never been united.”

Like many cultural scenes, the blues world is facing a racial reckoning in the era of Black Lives Matter. The old Black festival mainstays like B.B. King and Koko Taylor have passed on, and in their place the few blues fests still standing often program white guitar-wanking heroes, while traditional Black artists find their gig calendars empty. The blues may be at the root of contemporary Black expression, but it’s not uncommon to find white blues fans endorsing Trump or posting anti-Black Lives Matters memes on social media.

Holmes is far from surprised by the notion of Trump-loving blues fans or all-white blues festival lineups.

“I’ve always known about it, but now it’s just in the limelight more” due to social media, he says. “There are people who like Black music, they like to be entertained, but they don’t like Black people. That’s the way it is. It’s like a neo-Nazi liking klezmer music!”

The book also recounts two Professor Harp gigs in Roxbury that went over well but didn’t yield a third booking—or even a returned phone call. It’s typical of the greatly diminished respect for blues in the African-American community that Holmes also decries.

“Black people say they don’t want to hear that old ‘slave music.’ Even though I was born and raised in Boston, I had to rediscover my musical roots myself. But the blues is the original Black Lives Matter statement,” Holmes says.

One of the final chapters in the book is called “Solutions.” Besides calling for political and societal progress, Holmes praises several young Black bluesmen like Marquise Knox and Jontavious Willis, who he hopes will earn respect among Black and white audiences.

“It’s time to put the B back in R&B,” says Holmes.

When regular gigs resume, Professor Harp will do just that.

Professor Harp at the Porch Southern Fare and Juke Joint, 175 Rivers Edge Dr., Medford. Sat 9.5 free/6pm. theporchsouthern.com

Noah is an award-winning Boston-based writer and editor who covers music for the Arts Fuse. He has produced radio documentaries for @afropopww and researched and co-wrote the liner notes of "Take Us Home: Boston Roots Reggae 1979 - 1987."