Legendary Boston hip-hop heavyweight Dre Robinson has some unfinished business.

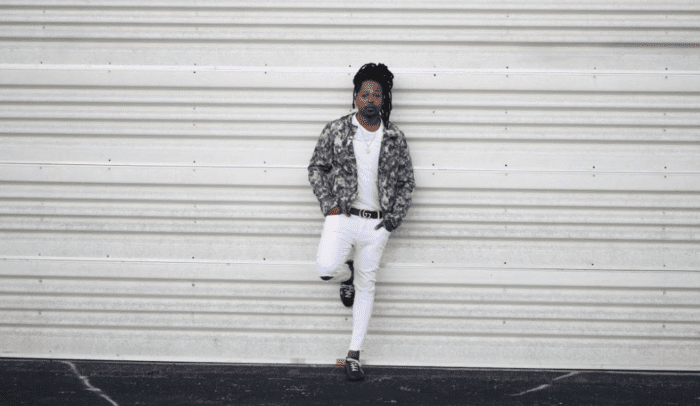

There’s a Fendi label draped across his back as Dre Robinson struts into the booth surrounded only by his art, his team, and his vision of success. He’s been gripping mics for decades; the way his granite punchlines hit over rolling drums signals experience, and in his case an end to a period of dormancy. Robinson has returned to the squared circle of music, pandemic be damned.

The MC nods in calm assurance as the music video plays on. An artist who’s considered all his angles, his song attests to luxuries he’s summoned to his grasp—by hook, crook, or otherwise. It’s “Prime Time,” because Dre “the God”—a scion of Dorchester who’s been using the force of his words to create better realities for himself since the Clinton administration—says so.

“Prime Time” is the premiere track off Golden in My State, a hard-knocking six-song EP that marked Dre’s return to regularly scheduled music during the pandemic. Robinson is 42, and these days hangs his fitted hat in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, but still raps like he’s boxing his way out of his Jacob Street neighborhood corner in Dorchester.

“It’s a new start,” Dre says. “I have unfinished business.”

Dre’s been making waves around and beyond Boston since the 1990s. He’s been living his dreams ever since, always in constant pursuit of his next best self. The whole ride, as he breaks down on “Prime Time,” Robinson has wrestled with the age-old dilemma of whether or not to dumb down his work to appease the masses.

Dre tends to see most things in flux. Everything comes in dichotomies: he’s a veteran of the game, but he’s held onto his youthful wonder within it. He’s a killer on the mic, but a celebrator in real life. He’s been around; he’s just digging in.

“When you achieve longevity, then you can say you’ve made it,” Robinson told a reporter back in 2005. “I want to leave my mark in the game.”

A decade and a half later, he’s collaborated with an endless list of icons. His 2004 single with Mobb Deep, “Get Right,” is a major point of pride for the Hub rap scene, while cuts with Nipsey Hussle, Jadakiss, Remy Ma, and Papoose also left impressions.

Fanatical types will tell you that no matter how much success you taste, there’s an ineffable attachment to victories that elude us. To that point, Dre is still hung up on Belichick’s vain calculus in benching Malcolm Butler for some bullshit reasons to lose Super Bowl XLII. He also has strong feelings about referees costing Garnett’s Celtics a second ring against their rival Lakers.

He’s seen the big arenas and run into obstacles along the way—all while staying focused on the bigger picture, the important stuff, like his son who is in middle school. It’s a theme that keeps on coming up, whether in conversation with Dre or in his lyrics: We have but one life to live, so you had better make it count, and do it your way. In Fendi, whenever possible.

The fast learner

Dre grew up fast. His father Derrick made his living off the grid, through business that often had him on the move between New York and Boston. “He was a hustler, so he used to do a lot of back and forth,” Dre, Jamaican-born and the eldest of his siblings, recalls.

Dre was 11 when his dad didn’t return from a trip. It was a few days before his stepmother, Maude, who raised him, got the nightmare call to come to Brooklyn’s Kingston County morgue to identify a body. Derrick Robinson had been shot six times near Eastern Parkway.

“It was brutal. And he was missing for a few days. And then, you know, we got a call. … Boom. He was dead.”

She moved the family to Dorchester. They settled on Jacob Street, near Norfolk Street and Woodrow Ave., then a hotbed of violence, by Dre’s account. “Fortunately for me, I was able to make it out of that environment without getting locked up or killed or anything like that,” he explains. “You’re able to get out of those situations unscathed. You navigate through it.”

As a student at East Boston High School, Robinson refined his ability to improve the inefficient systems around him. “I manipulated public schools,” he says of the 65 days he skipped his sophomore year. Decades later, he explains his exit strategy through music.

“Nas was like an older brother for me,” Dre says. “He would just take me to different places, mentally, because of the way he uses his words and the stories he would tell.”

After East Boston High, Dre had ambitions for college, but navigating his outsize responsibilities came at cost. “I wasn’t able to go to college, for certain reasons,” he alludes. “I wanted to, but it wasn’t in the cards for me.”

Still, there was music.

“I realized this could be a thing for me, out of high school,” he says.

Contract killers

Contract killers

Shrouded by a scarlet hood, a matching pastel bandana affixed the way we used to only associate with banditry, and tight black shades, Dre cuts a dynamic if chromatic figure as he takes the stage. He has a label deal, and this is a world where that still means everything.

It’s the 2006 Boston Beat Battle, and Dre is a rising star. Feature on a DJ Kay Slay mixtape; “Get Right” hit across the country. The show should correspond with the arrival of Dre’s debut feature album, but even as he racked up spins and accolades, things stalled. A full studio album was shelved, along with that path to the majors. It’s a story that you’ve heard before. Dre was stuck in a bad deal.

“At that time, I was just a broke kid that loved to write music. And they said, Sign.”

So he did.

“Everyone wanted the [label] deal—they wanted that machine behind them,” he says. “Versus now, artists these days are the label—their own label. All they need is something to connect to the internet, and boom.”

He likens the label gauntlet to his equivalent of a college experience.

“We were ahead of our time. … Listen, everybody that gets a degree doesn’t mean that they’re going to use that degree and everything that they learned in what they were trying to learn in school.”

His colleagues and classmates: DJ Khaled and Statik Selektah, for starters, whose seminal mixtapes Dre left dents on. Still, most of his inaugural work remains walled off, largely unreleased and only in possession of DJs and collectors who know where to look. The failure to launch as anticipated still stings.

“The label didn’t know exactly what to do with me,” he recalls. “I was telling a hard, gritty, type [story]. I was so focused on delivering my craft a certain type of way, like television. Like a perfection, but also tunnel vision. I didn’t have a wider view.”

The gamer

“It’s bigger than where we come from, you know? It’s bigger.”

Given the hysterics of the past year, when Dre turns on the tube, it’s to load a gaming entertainment system.

“I don’t even put on regular TV anymore because the shit is so saturated, and it’s overwhelming at times to see the shit. If they’re not talking about the COVID they’re talking about the Black Lives Matter protests, and racial injustice, and the systemic, whatever shit.”

Dre knows all about racism and limited opportunity. He just doesn’t see much hope in nightly newscasts.

“There needs to be change,” he says. “I don’t feel like it will ever be an equal opportunity type of thing, but they can make it where there is opportunity … where it works like it’s supposed to and people aren’t dealing with the injustice that’s been going on for so long.”

He’s caught a beat …

“How long are the signs going to be held up to see that there’s no timer on it, and that something definitely has to happen? How long is that?”

Of course, Dre is once again adding his voice to the mix. He’s off the sidelines, and during the pandemic passed time in part by recording a series of #50forFriday Instagram freestyles. They’re impressive feats, with him delivering 50 lines of brand new thoughts to unpack for an uninterrupted 20-week run. Dre also brought collaborators on to help knock out as many installments as its namesake calls for.

With less to prove, Dre has more to share. His mother with whom he was close is gone, but music has become a family affair of late, with Shall, a younger brother he has long looked after, becoming his top co-writer, even providing hooks and verses.

“I progressed,” he says. “Your view kind of broadens. And you’re like, Well I don’t have to trade what I do, but I can learn from what that person does and kind of incorporate some of that into what I do.”

As for his rhymes …

“It has to be a balance,” Robinson says. “I search for the balance. … I’m like Dre, you have to kind of tap into your vulnerability, be a little more vulnerable. Allow people in a little bit. There are characters, there are people in your life, you’re telling a story, stories, movies have characters in them. Bring some of these characters to life for people so that they can actually know who you are, and they can love you and these characters as well.”

The risk

In recent years, Dre’s seen growth in opportunities for music coming out of Boston. More power from more people he trusts can be seen in more places. “They’re in positions in the industry that they can shed light on Boston, on the community here,” he explains. “That wasn’t happening before.”

At the same time, he’s not back in the game on account of anyone else’s hype. Now a happy, home-owning Rhode Island dad, Robinson had to come around on the idea of giving his rap career another go at 42. It meant overcoming his own latent fears of ageism in hip-hop. Putting this record out felt like a risk, until he considered why.

“I used to be scared of people being like, Oh, this old cat, why is he still doing this? But I feel like now it’s okay to make music because … you have a core fanbase and there’s no age on that. People want good music, and if you could create that, then create it.”

For all the trappings, it turns out Robinson’s beliefs are pretty simple: do, try, provide, be yourself. Chains, cars, fashion shoes—it’s all just dressing.

“You don’t put an age limit on country music; you don’t put an age limit on R&B—Why are you putting it on hip hop?” he says. “If you can still make good music, then make good music. It’s growth.”

Speaking of growth, his teenage son, Andres Jr., or “D2,” has helped him sharpen his focus. Leaving Boston for Pawtucket has proven to be worthwhile. “It’s super, super peaceful. Me and my son are just chilling. I’m into, like, doing my lawn.

“He’s almost my height. I’m 6’1, he’s about 5’9. He does not want to pick up a basketball, or play any sports,” Dre says.

It’s a long way from Jacob Street.

“This kid does not like conflict at all.”

“He’s that kid, I’ll be telling him something, I’ll be talking to him, and he’s like, Okay, Dad, I’m just going to go to my room.”

Because if there’s one thing Dre always wants, it’s one more bar.

“I’m like, Why? I want to finish this conversation … ”

Brendan McGuirk is a writer living in Greater Boston and has written for publications including the Boston Metro and the Boston Herald.