Slavoj Zizek and how the pandemic has undermined “the coordinates of our basic access to reality.”

On Inauguration Day, a viral meme of Bugs Bunny in a tuxedo read: “i wish President Joe Biden a very pleasant owing me $2000.”

Whether or not Biden lives up to the so-called “most progressive platform of any major party nominee in history,” one thing is certain: Our expectations have risen. Barely over a decade ago, it would have been ludicrous to suggest Obama’s financial recovery package include a direct check of $2,000. Now, we expect it; Joe Biden owes us.

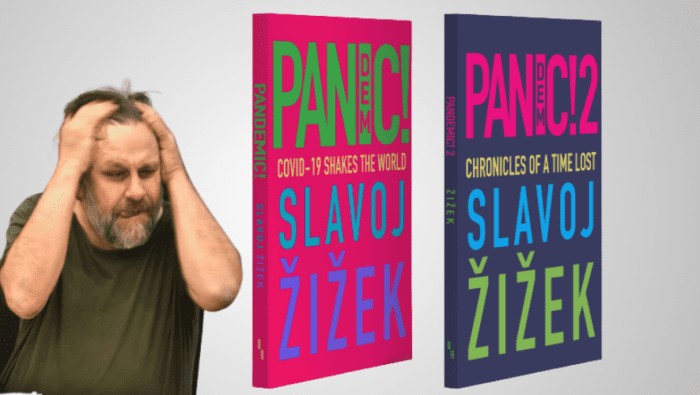

Slavoj Zizek’s latest two books, Pandemic: Covid-19 Shakes the World and Pandemic 2: Chronicles of a Time Lost, examine how the rolling, exhausting crisis of the last year has altered our material conditions and our collective psyches, from the way we dream to what we expect.

Riffing on Naomi Klein’s analysis of “disaster capitalism,” Zizek remains hopeful for a corresponding “disaster communism,” where the state assumes “a much more active role.” When Zizek uses the term “communism,” he means it loosely, as any policy that cuts against capitalism’s profit motives for the purpose of benefiting the general welfare of all people. What few measures states have taken, like direct aid, though they have not gotten close to “guaranteeing the minimum of survival,” still point out a cautiously optimistic solution.

The first book of the two examines the pandemic’s immediate fallout through Zizek’s personal reflections written in the first few weeks of lockdown last March and April. Maybe because it comes so early in the crisis, Zizek appears more hopeful for a dramatic climax and a productive state response, even as he diagnoses how flat-footed governments were.

The image of state power Zizek puts forward often finds itself awkwardly revealed: Politicians could help, but don’t; leaders remain both too unwilling and also too inept to do so. Because of that unfulfilled possibility—–if the government can just send us $1,200, why can’t it end poverty and homelessness?—–the pandemic brings us to a place where “the impotence of power is now laid bare”: Tthe cat “reaches a precipice, but it goes on walking, ignoring the fact that there is no ground under its feet.” For all the anti-maskers out there, the general sentiment “from us, the subjects, to state power is that we will gladly follow your orders.” But the orders come too late, never come, or else miss the point.

As interesting and philosophically dense as his political analysis is, Zizek’s pamphlet-sized books offer a remarkably friendly style. His short, witty essays gloss everything from sexbots to high Freudian theory, and mostly leave out the jargon. In one piece, Kill Bill’s “Five Point Palm Exploding Heart Technique” resembles the effect of the pandemic, because of the way small pressure points set off the systems’ overall failure. Zizek moves briskly from Quentin Terantino to Marxist theorist Fredric Jameson, who like Zizek finds hope even in society’s general collapse, just like “the utopian potential in movies about a cosmic catastrophe.”

If Zizek’s first pandemic book presents astute political analysis for the type of person who appreciates both pop culture and Hegel, his second book launches an even more sophisticated psychological analysis. In Pandemic! 2, with a few additional months of quarantine under his belt, Zizek begins to describe COVIDovid-19 less as a single traumatic break and more as an ongoing distortion. COVIDovid-19 has a “non-apocalyptic character,” Zizek writes, because “the process of disintegration just drags on with no end in sight.”

This second volume then ends with two much longer and more complex musings on the psychic space of our “common customs,” what Lacan called the “big Other.” Zizek describes a “ontological catastrophe,” resulting from the pandemics’s “undermining of the coordinates of our basic access to reality.” Here Zizek can go beyond the simple idea that the COVIDovid-19 pierced the dream of globalized capital, and unpack the waves of reaction to that piercing. For example, those who dismiss the need for masks, have reacted to the rupturing of our common reality with what he calls a “will not-to-know.”

While at times the Freudian dream-speak feels somewhat abstracted from the urgent politics of the moment, Zizek’s psychoanalysis comes as one of the few footholds available in the slipperiness of our cultural landscape. Since the pandemic precipitated not only a material and also, of course, a health crisis, but a subsequent collective mental unravelling, what better language for analysis than Freud’s?. And who better than a friendly, curmudgeonly, Marxist-aligned critic like Zizek?.

Zizek’s persona comes across as charming and open, though his blustery, contrarian style presents occasional problems. For example, he argues effectively that the left should not cede the classic enlightenment thinkers to the right, but his defense of the white, male canon edges into exaggeration—–how much do we need Thomas Jefferson, really? And when Zizek translates complex theorists like Lacan into simple language constrained by two very short books, I worry he leaves too many of the nuances of his own ideas on the cutting room floor.

But by and large Zizek’s texts put forward an accessible and astute psychological analysis of the moment. Because that “big Other” of everyday norms, is “simultaneously disintegrating, displaying its inefficiency, and tightening its grip,” the various reactions, from conspiratorial denial to obsessive hysteria, begin to make more sense. Zizek’s treatment for our mental disorder, then, means fixing the underlying problems that Covid’s revelations have only made clear. In other words, the only way out of this psychic disintegration involves a robust material response: Joe Biden owes us at the very, very least, $2,000. Or, as Zizek puts it: “Communism or barbarism, as simple as that.”

Max is a PhD student in English and American literature at BU. Previously, he worked at the NGO GiveDirectly, an organization that sends cash transfers, no strings attached, directly to extremely poor families. In 2014, he studied and wrote poetry in Wellington, NZ on a Fulbright scholarship.