When Greater Boston’s Golden Age of scholastic sports captured national attention

Forty years ago, Eastern Massachusetts experienced a golden age of high school sports.

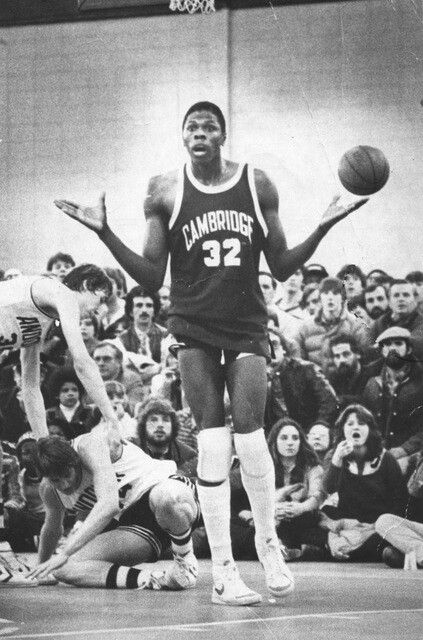

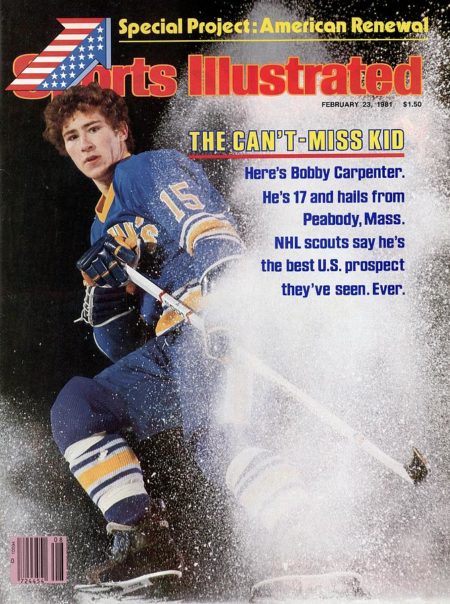

In 1981, the most recruited hockey player in the US was Bobby Carpenter of St. John’s Prep in Danvers, while the most recruited male basketball player was Pat Ewing of Cambridge Rindge and Latin.

There were many other outstanding athletes, such as running back Jay McGee of Brockton (class of ’82, on a football team ranked number 1 nationally) and Brockton’s tight end Mark Bavaro, class of ’81, who also starred in track and field and after that became an All-American at Notre Dame and played in two Pro Bowls.

Meanwhile, Glen Gonsalves of Falmouth was high-jumping 7’3” at major Eastern track meets in 1981.

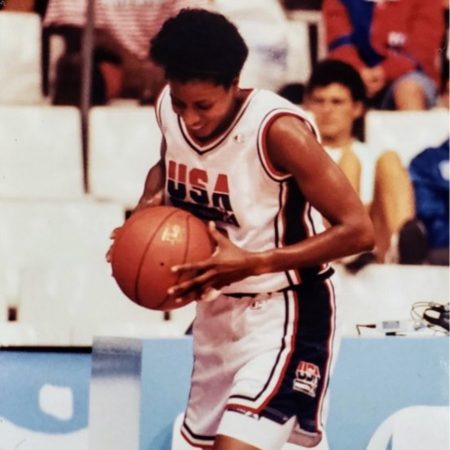

There was Brookline High basketball ace Fred Hill, Natick High quarterback (and basketball star) Doug Flutie, girls’ basketball stars Medina Dixon of Rindge and Michelle Edwards of Cathedral, and Robin Christian of Jamaica Plain—all of whom went on to star at prominent university programs and played professionally.

And then there’s Dorchester High basketball star Eugene Miles, Boston Globe All-Scholastic Craig Walker of Chelsea, and All-Scholastic basketballer Peter Wynne of Beverly High. In 1980, Lynn Classical, featuring Primus and Pancho Bingham, beat Rindge and Latin in a scrimmage at Milton High. Primus went on to play basketball at BC, Bingham at BU. Meanwhile, Butch Wade was starring at Boston Tech—before a standout career at the University of Michigan. Wade enrolled at Michigan the same fall as Bourne High School running back Bob Perryman.

All things considered, Greater Boston scholastic sports was experiencing an unprecedented (and unsucceeded) renaissance. A generation of children reared on stories of Cousy and Ted Williams, raised watching the Bobby Orr B’s on TV. Youth who were weaned on the sports columns of Bud Collins, Will McDonough, Bob Ryan, Leigh Montville, Peter Gammons, and Dan Shaughnessy. And that was just in the Globe. They also saw Len Berman, Dick Stockton, and others before they went national. The Bobby Orr rinks helped fuel the explosion. So did basketball opportunities such as the BNBL and the Boston Shootout.

New routes

The dispersal of talent, particularly in basketball, was fostered by Black upward mobility embodied in migration from Roxbury, Dorchester, Jamaica Plain, and Mattapan, to Randolph, Newton, Framingham, Natick, Milton, and Stoughton. In addition, forced public school busing pushed Roxbury’s athletes to South Boston, Charlestown, and Hyde Park high schools.

In 1974, federal Judge Arthur Garrity ruled that any schools with a student body more than 50% nonwhite be “rebalanced” by ethnicity. When the Boston School Committee rejected Garrity’s plan, the US Supreme Court required it be implemented. By 1981, it was in full force. When the 12th graders of 1981 had been sixth graders, the experiment resulted in violent attacks on Black students attending school in Southie, Charlestown, and other white areas.

And with opportunities through Metropolitan Council for Education Opportunity (METCO), now the longest continuously running voluntary school diversity program in the US, parents of city teens took advantage of the chance to enroll them in upscale or suburban schools. METCO was developed based upon a study by Dr. Ruth Batson about the equally poor graduation rates, dropout rates (50%), and lack of college enrollment of students at South Boston, Charlestown, Hyde Park, and the Roxbury secondary schools. It was launched under the auspices of the Massachusetts Racial Imbalance Act of 1966.

At the time, a future 1981 high school senior would have been three years old. In its initial year, seven schools participated in METCO, involving 220 students. By the mid-’70s, this redistribution benefited the Black athletes, the white athletes, and their coaches. In basketball, Bobby Carrington had starred at Archbishop Williams of Braintree, David Thompson at Stoughton, and LeJuan “Buddy” Brantley at Bishop Feehan in Attleboro. Billy Raynor and King Gaskins of Catholic Memorial’s early 1970s teams, and Felton Sealy, a Parade All-American who graduated Don Bosco in 1976, exemplified an influx into the local Catholic programs.

Suburban and private schools boasted significant talent, and promising white stars such as Ronnie Perry of Catholic Memorial and Bob Bigelow of Winchester ventured into Roxbury to test their mettle against these players. Roxbury community leaders such as Alfreda Harris, Jeep Jones, and Roscoe Baker shepherded talent at centers like Norfolk House, the Shelburne Center, and the Cooper Community Center. There were places to play. Boston entered sports teams in the national Youth Games and the Junior Olympics.

Raised on champs

It was a generation of youth raised eating Big Yaz Bread. During the dramatic 1975 World Series, the class of ’81 were sixth graders, up late and on the edge of their seats when Pudge Fisk’s homer won game six. On Oct 2, 1978, when Bucky Dent broke their hearts with his homer in the American League East Division tie-breaker game, they were 14- or 15-year-old high school students—already competitive in sports. The 1978 Patriots were 11-5, led by QB Steve Grogan, fullback Sam “Bam” Cunningham, wide receivers Stanley Morgan and Harold Jackson, defensive backs Mike Haynes and Raymond Clayborn, and Pro Bowlers tight end Russ Francis, guard John Hannah, and offensive tackle Leon Gray. The students grew up on competitive football teams, Stanley Cup winners in hockey, and NBA champs like John Havlicek and Dave Cowens.

The influence of the NHL champion Bruins, particularly young 1970s star Bobby Orr, cannot be overlooked. In the mid-to-late 1960s, the MDC (Metropolitan District Commission) built rinks in a number of communities in Greater Boston and beyond. Children flocked to these rinks to play street hockey, or participate in organized youth leagues. Others just learned; skating instructors Rosemary Hanley and Carol Butterworth (McKinnon) brought their programs to many of those rinks. Soon there were so many interested kids, more instructors became involved. The aqua blue rinks were a community staple.

On May 10, 1970, most kids in the class of ’81 were seven years old when Bobby Orr scored his game-winning, cup-winning goal and famously flew through the air. More and more of the TV 38 generation of young Bruins fans gravitated to MDCs rinks in Revere, Charlestown, Dorchester, and Cleveland Circle, while the Bruins practiced at HockeyTown Arena on Route One in Saugus. As a result, Greater Boston became a high school hockey hotbed.

“We were at the tail end of a great era in Boston sports—the Big Bad Bruins; Havlicek, Cowens and the Celtics; the Sox and Fred Lynn and Jim Rice,” said Jay Ash, former Chelsea High School basketball player and Chelsea city manager who also served as housing and economic development secretary for Gov. Baker. “Heck, even the Patriots were piling up wins on the way to respectability. All of us wanted to grow up and be them, and all of us went out to our parks. Heck, I went out to our street and tried to play like them.”

Front and center

Pat Ewing came to Cambridge from Jamaica at age 13, after having been raised on soccer and cricket. Cambridge in 1976 was the ideal place for him to be mentored in a new sport—basketball. The local high school star, Paul Little of Rindge, was a Parade high school All-American, but the athletic tradition at Rindge long predates Little or Ewing. The school produced several of Greater Boston’s Black semi-pro baseball stars of the 1930s, and also graduated John Thomas, the first athlete to high-jump seven feet indoors, as well as Charlie Jenkins, a 1952 Olympic 400-meter dash gold medalist. Over the years, community basketball talent was often tutored by an older alum named Francis “Rindge” Jefferson. One of his mentees at the Cambridge Community Center was a small guard named Mike Jarvis, and the heavy pickup games took place at Hoyt Field and Corporal Burns Park.

In 1962, Rindge (then “Rindge Tech”) won the state Tech Tournament at the Boston Garden. “Rindge” Jefferson was a smooth, 6’2” wing player for the semi-pro Boston (Colored) Bruins, a former star at Kentucky State. It was he who tutored a husky Roxbury 14-year-old named Jimmy Walker in the finer elements of the game. Rindge’s hours with Walker paid off in the latter, leading the nation in scoring as a Providence College guard. That status earned him a number one overall NBA draft selection in 1967 (18 years before Ewing, having been mentored by Jarvis, garnered the same distinction).

When Ewing was an eighth grader, his phys ed teacher, Steve Jenkins, introduced him to Jarvis, who was then an assistant college coach. Pat started learning the basics and went to Hoyt and Burns to watch pickup runs. One day he saw Xaverian High alum and Rutgers All-American Jammin’ James Bailey play there. Northeastern assistant coach and former Huskies player Joe Delgardo and others worked young Ewing out at the Roxbury Youth Center. Toughened him up. He would need it, and not just on the court.

Jarvis became the head boys’ basketball coach at Rindge, Steve Jenkins his assistant. Ewing enrolled in the ninth grade, and the team was making the news two or three times a week by his sophomore season. It was by no means a one-person team. Rindge benefited from excellent guard play by performers Karl Hobbs, who controversially transferred from Jeremiah Burke, Kevin Headley, and Ladon Adair. Early in Pat Ewing’s career, they had a strong forward named Billy Ewing (unrelated). With success, came haters. At away games, students threw rocks and bricks at their team bus or slashed its tires. The Rindge players were called racial slurs by opposing fans. Skirmishes even broke out on the court.

Rindge persisted, running off a 34-game winning streak. The loss (65-58) was to perennial New Haven power Wilbur Cross in 1980, at New Haven Coliseum. Wilbur Cross had a 6’9″ center named Jeff Hoffler who had faced Ewing a couple years earlier at a summer tournament in Detroit. Years later, Jarvis told a New York paper Ewing had been ill with the flu and shouldn’t have played.

In 1981, Bostonians hoped Pat Ewing would stay home and continue his basketball career at BC. On Feb 3, 1981, Ewing, his parents, Jarvis, and Jenkins held a press conference before 200 onlookers—150 of them media—at Satch’s Restaurant (owned by former Boston Celtic Satch Sanders). Ewing announced his decision to enroll at Georgetown, where he would play for former Celtic John Thompson.

Jarvis was asked if the decision was final. “There is no doubt in my mind that this is it.” Maryland coach Lefty Driesell said, “If I were [Georgetown coach] John [Thompson], I wouldn’t relax until the day he registers for classes.”

Jarvis also said the coaches from the six schools courting Ewing—Georgetown, North Carolina, Boston College, UCLA, Villanova and Boston University—had not been notified of Ewing’s decision before the press conference.

The Carpenter

The Carpenter

In 1979, Bobby Carpenter led Danvers St. John’s to a prep championship. Coached by Winnipeg Jets scout (and paint salesperson) Joe Yannetti, the St. John’s hockey dynasty coincided with that of Ewing’s Rindge teams. Carpenter, co-captain John Turner, Kevin McKenna, and Dave Tewksbury played state playoff games before capacity Boston Garden crowds. They upset schools such as Matignon and Burlington.

In the summer, Carpenter, a Peabody native, played for Gregory’s Deli. Because of his celebrity, he met that other local hockey hero Bobby—Orr. Orr gave Carpenter tips not only on ice skills, but on dealing with media demands. At Town Line Twin Rinks on Route 114, pro coaches, scouts, and agents attended Carpenter’s games against teams such as Moynihan Lumber. This had been the case since he was 10, when opposing teams had to assign two defenders to Carpenter.

In 1981, Bobby Carpenter graced the cover of Sports Illustrated. He was carrying a scholastic grade average of 93. His dad Bob Sr., a police officer, favored a collegiate path for his son. But Bobby was selected third overall in the 1981 NHL draft by the Washington Capitals—after leading the United States with nine points in five games at the World Junior Championships. After signing a letter of intent to attend Providence College, he became the first player to make the jump from a US high school straight to the NHL.

As a pro, Carpenter didn’t disappoint. He scored 32 goals and 67 points as a rookie in 1982 and set career highs in 1985 with 53 goals and 95 points. He became the first US-born player to score 50 goals in a season and played in the 1985 NHL All-Star Game.

Ewing, meanwhile, played in three national championship games at Georgetown, winning one (and coming within four points of winning all three). He enjoyed a Basketball Hall of Fame career with the New York Knicks and today coaches at Georgetown.

Looking back 40 years, it’s clear that a perfect storm of local pro sports success, excellent sporting media, and critical local opportunities to learn and thrive at community centers, hockey rinks and summer basketball leagues fostered a peak period in scholastic sports that will never be forgotten. Six years after the Hub earned national headlines for the clashes of forced school busing, a nation turned its eyes to number one talents Carpenter and Ewing, wondering where they were headed next.

This article was produced in collaboration with the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism.

Bijan C Bayne is the author of Martha's Vineyard Basketball, and of Elgin Baylor. He is producing a docuseries about Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. He will be producing live readings of the original The Twilight Zone with a theater group on Cape Cod.