“Knowing Storage Space was going to happen and be presented in locations not designed for artwork display gives artists and communities our power back and a chance to do intriguing work.”

When most of us think of the word “storage,” we likely imagine some kind of designated area for the items we cherish or at least need from time to time. But for Rudolf Lingens, artist and founder of the secretive Imaginary Collective, there are much more prominent demarcation lines at play.

“Storages are, in a sense, a bourgeois extension of closet space for the middle class,” Lingens explained.

Meaning that on the flip side, the need for storage could signify deafening financial woes.

“Economically precarious people sometimes find that storage space can mean temporary placement—where items go when transitioning. Especially with how common they’ve become as an industry since the [2008] financial collapse.”

These days, we can also tie the storage industry to the COVID-19 pandemic. As reports of evictions and alleged exodus have shown, many people have been forced to move out and reside (or crash) elsewhere due to job loss or the inability to pay rent on time, and that could’ve also meant leaving personal belongings behind.

“Storage space is deeply tied to the housing crisis,” Lingens concluded.

When first interviewed back in January, before the Black Lives Matter awakening, Lingens connected the concept of storage to the physical act of cultural, racial, and xenophobic policing. The comparison was clear, based on how ICE detention centers were overcrowded with immigrants, and the situation causing national outrage.

“[And] those immigrant detention spaces? They look like storage spaces,” Lingens asserted. “They’re constructed of the same fencing, concrete, and metal, and used as these incredibly dehumanizing expressions of excess labor force and the criminalization of identity.”

People have long understood storage in terms of objects taking up space. But what about everything (and everyone) else that gets sheltered?

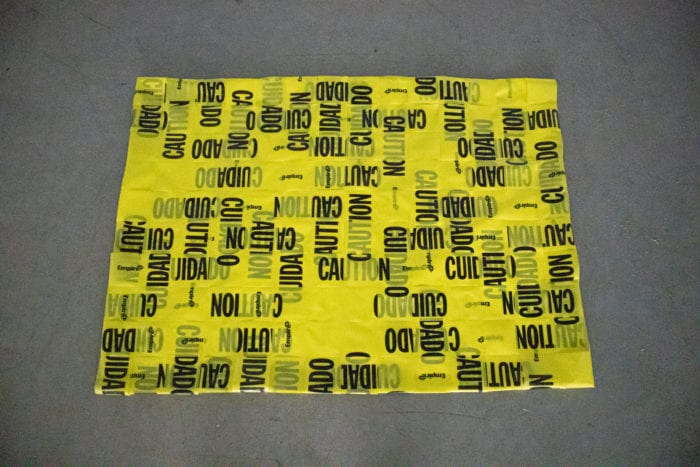

Last winter, Lingens and the Imaginary Collective explored such covert realities in their debut show, Storage Space. For the ambitious project, art was displayed within rented storage units at an undisclosed location—sans permission from the facility.

“I came up with the Imaginary Collective a while ago, and it’s a confluence of interests,” Lingens said. “[It’s] the evolution of my thinking about the types of work I’m into, such as collectivized art-making, as well as conversations I’ve had with artists and friends over the years.”

He curates, conceptualizes, and administrates for the collective, which is motivated by the quote act as if you are already free.

The “collective” label itself is a nod to anarchist and socialist writers and thinkers, with the “imaginary” preface coming from Tiqqun, a French leftist journal that only published two editions, between 1999 and 2001, but in its short time promoted the idea of an “imaginary party.”

“[Tiqqun envisioned] this idea of an invisible political party that was formed for people that didn’t consent to state capitalism,” Lingens said. In essence, such a party would respond to “how power structures are supported by a minority of a population, while the imaginary is incredibly powerful and representative of the majority.”

Lingens added, “But the thing is, the moment resistance becomes visible, it becomes identifiable to society and faces the possibility of co-option, interjection, or just outright being crushed.

“We’ve seen how mainstream media can sometimes portray transgression in ways that still tone patrol. There’s an ‘appropriate’ way to express Black Lives Matter. To express Occupy movements.”

In the coming months, the Imaginary Collective’s clandestine sophomore show will aim to both highlight and avoid those traps, while ardently detailing the struggles of social movements, the presence of gaslight culture, and acknowledging what the art world has endured for promoting justice and autonomy and representing inconvenient truths.

While the location will again be confidential, Lingens said, “We want to occupy spaces that are not art spaces, and where we weren’t given permission to show. [So afterward], we erase our presence there and disappear.”

The disappearing act is also simply not an act—it keeps the collective’s most vulnerable talent protected. Images of the art are later shared on Instagram. “We want to be thoughtful about how the work is created and that the artists aren’t jeopardized,” Lingens said. “To some extent, the way we’re transgressing is an expression of privilege, but also a deconstruction of it.”

Three artists that showcased for Storage Space—Janet Loren Hill, Alejandro Macias, and S.T. Barry—delved into deconstructions that were either personal or historical.

“Joining has allowed me to take my art into an advocate role,” Hill, a MassArt grad, said. The collective has made her a braver creative. “It’s nice to have an avenue in which my art can take up space in a declarative way and be incredibly generative. I used to be hesitant about any dogma. But the structure of the collective allows for showing the contradictory nature of things.”

Hill used the show to examine the anxiety of walking alone at night in When I pretend. A spiraled object made of pool noodles, lined with bold neon, and with her overreaching plastered arm above it, the spirals look as if they want to expand, but don’t in order to protect itself from harm.

“I had so many thoughts about how to respond to this project,” Hill said. “I love to walk around at night and see the orangey glow of windows in the darkness and against the deep-blue shift at night. Especially at sunset and how the sky surprises us with what it’ll become.

“Yet as a woman, the sunset is also an alarm because it’s saying, You better get inside, or else. … I thought of my own experience, but also of those that have also felt socially vulnerable at night. If we wanted to truly act as if we were free, we would walk around fully exposed at night.”

Storage Space peer Macias presented an explicitly confrontational illustration. His They’re Everywhere is a headshot of a blankly staring, KKK-evoking figure, with a slight cone hood outlined in hot pink.

“I did make it somewhat menacing,” said Macias, who completed a MassMOCA residency in January. “It speaks for itself. A lot of the work I make is socially political, and that kind of work will spark feelings. As an artist, I also worry about censorship. So when Rudolf brought the idea of putting out secretive work and documenting it, I felt my work would align very well.”

Inspired by the horror that unfolded in Charlottesville, Virginia, around a so-called Unite the Right rally on Aug 11, 2017, They’re Everywhere also reflects the groundbreaking works of Texas artist Vincent Valdez’s Strangest Fruit, a series that emphasized the lynching of Mexican men, and his 30-foot panel The City I, which Hyperallergic described as a “massive panorama [that] depicts a gathering of the Ku Klux Klan in modern times, with a Chevy truck, glowing smartphone, and surprisingly malicious-looking, hooded infant coddling a Pikachu plush, marking the scene as unmistakably current.”

“When Trump was elected, a lot of people felt empowered, and specifically white nationalists and supremacists came out of hiding,” Macias recalled. “[I remember watching that] VICE documentary on the Charlottesville riots and [the racists] were angry. It was like they came out of nowhere. If anything, out of hibernation. And I think that’s what’s scary. They’re among us. They’re here. They never really disappeared.”

For Bellingham native S.T. Barry, the collective is bridging the gap between the historical elitism of many art institutions and the increasing accessibility of art (online) today. Along with Hill, Barry is thankful for the chance to create without confinement.

“Especially right now, it’s not always easy to get your work out there and find like-minded artists,” Barry said. “Knowing Storage Space was going to happen and [be] presented in locations not designed for artwork display, gives artists and communities our power back and a chance to do intriguing work.”

A self-described idealist, Barry presented Day Dreaming as a deliberate misnomer. Amongst the cheerful colors, a closer look reveals a lot of commotion. As one bluebird curiously gazes at a bowl of cereal; others are perched on a chair. On the ground, animals engage in cannibalism, as a deranged Muppet-like bust observes from the wall.

“Within varying degrees, I hope that humor pops up in my work,” Barry admitted. “I would rather laugh at tragedy than cry at it [and that’s because] when something bad happens to me, I look for the irony, so as not to feel too beat down.”

Hearkening back to childhood faves like Mister Rogers and Jim Henson, Barry experiments with surrealism, and Day Dreaming is a disturbing, frozen-in-time snapshot of disparate experiences. The opportunity to expose such chaos is, what it seems, the Imaginary Collective is willing to fight for.

“Cute and terrifying at the same time,” Barry said. “That’s the world.

“It’s a beautiful place, and horrible things happen. [We can’t allow] the horrible things to override the beauty. I’m trying to be honest about the pros and cons of the different ideas of freedom too. They coexist.”

imaginarycollective.com

This article was produced in collaboration with the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism

This article was produced in collaboration with the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism

Shardae is a writer covering music, film, and arts in Greater Boston.