On the afternoon of March 5, 1976, a fallen Boston sports idol sat in a downtown diner and stirred cream into his hot chocolate. “Guys stop me on the street all the time and ask me if I used to be King Gaskins,” he said. “People ask me if it’s true I went to jail, if it’s true I was in a bank robbery, if it’s true I was pushing and shooting drugs.”

On the afternoon of March 5, 1976, a fallen Boston sports idol sat in a downtown diner and stirred cream into his hot chocolate. “Guys stop me on the street all the time and ask me if I used to be King Gaskins,” he said. “People ask me if it’s true I went to jail, if it’s true I was in a bank robbery, if it’s true I was pushing and shooting drugs.”

The 21-year-old former athlete was sitting with Boston Globe reporter Peter Gammons, who had chronicled the legend of Gaskins since the beginning, from the jump shot he’d sunk to win the state championship as a freshman in 1969, to three all-state honors, to a Massachusetts scoring record, to the barnstorming team that put Boston on the basketball map. The Final Four was a few weeks away at the time, and the guys King once conquered had become major stars on college basketball’s biggest stage, but King had no such plans on the morning he sat down with Gammons. The only All-American in Boston hoops history left the diner and headed downtown to his job selling magazines over the phone.

The story wasn’t as sad as it sounds. Gammons noted that Gaskins still had his regal air. The King hasn’t changed much, the writer thought. He’d grown a beard, but still flashed the same charismatic smile.

“I try to laugh it off but I can’t always,” King said of the exaggerations of his demise. “It’s all so crazy. No, I say, I never have been in drugs, no I never robbed a bank. What I did was break the law and what I did was stupid, and what I did hurt me and people who had been good to me. But the things people spread around …”

Outside that diner, in the year of America’s bicentennial, Boston high school sports were overshadowed by the battle over school desegregation, and King was no longer basketball royalty. He had slipped through three colleges in as many years and was about to be shut out of big-time hoops forever. “I’m interested in finishing school and working with kids,” he said. “But I guess I have to outgrow my past before it can happen.”

BECOMING KING

Gaskins had been the Hub’s anointed one since he was a skinny freshman. It was a mythical time—’60s and ’70s basketball in Boston, full of pioneering all-black high school squads and playground legends who outplayed pros. Yet it was Gaskins who inspired the most crowds, writers, fans, and coaches.

Some say the legend began on March 24, 1969, when Gaskins and his Catholic Memorial High School squad played Springfield Commerce for the state title. A clash of two undefeated teams, it’s still often recalled as the greatest game in Mass hoops history. With five seconds left and Springfield up one point, the CM ball swung to Gaskins, the least-feared player on the court. Springfield was daring him to shoot. Twenty-five feet from the goal, Gaskins spun the rock in his hands like a globe, took a deep breath, and launched one into the bottom of the net. A hero was born. Sitting in the locker room after the game, he told Gammons, a rookie reporter at the time, that his broken finger had affected the arc on his jump shot all night—until the last shot. “No matter how much it hurt I wasn’t going to ease off on that shot,” he said. “Nobody but nobody is going to get this ball away.”

In the Mission Hill community where Gaskins came of age, basketball was seen as a way to rise out of troubling conditions. The neighborhood’s rich sports tradition had already carried his cousin, Jimmy Walker, to the NBA as the number one draft pick in 1967, and Gaskins hoped his immediate family would be next. In August 1968, when Gaskins was 13, the Globe detailed some of the conditions in his area: “Mission Hill residents are frustrated daily in attempts to get improvements and repairs … Mothers must send their children out to play in areas which are full of trash.”

On the housing project basketball courts, Gaskins worked on his jump-shot religiously, the “ching” of swishing chains rattling neighbors well into the early morning. “I had the dream,” Gaskins said. “We used to say, ‘NBA—the only way.’ That’s the way we thought.”

As early as his sophomore year of high school, Gaskins saw his dream getting closer. Chuck Daly, then the new head coach at Boston College, said Gaskins was the best high school guard he had ever seen. “He’s going to be super,” said Daly, who went on to win two NBA championships and an Olympic Gold Medal in a Hall of Fame coaching career. “Matter of fact I have a uniform that could fit him right now.”

In his second year of high school, Gaskins made history when he was named to the Globe All-Scholastic team. No sophomore had never made the All-State team before, and Gaskins shared the honor with another super soph—Ronnie Lee from Dorchester, who attended and played for Lexington High School as one of the first students in the still-running METCO program.

Over the next several years, Lee and Gaskins electrified hoops fans from Southie to Springfield. From 1968 to 1972, their success was also set against an increasingly intense battle over school desegregation. The tension had reached unprecedented levels by the time Gaskins and Lee, both in their senior seasons, faced off in the 1972 state championship. On game day, the Globe’s Leigh Montville wrote, “Two teams of destiny meet in a dream state final. We will witness what we have been waiting four years for.” Gaskins ran “around and over and through at least five different people assigned to guard him,” and scored 40 points in a loss. Montville also recognized the game’s social significance in the next day’s coverage. “Lexington had been the winner 76-69 to take the State Division 1 basketball title. But these two kids, these two gifted black kids who had dribbled into predominantly white worlds and succeeded had been the show.”

KING DYNASTY

Boston’s class of ’72 confirmed the city’s standing as a basketball town; besides Gaskins and Lee, standouts included Carlton Smith, Will Morrison, Bobby Carrington, and Billy Collins. They were dubbed the Boston Six, and that summer they teamed up to play the best squads on the East Coast. “Boston didn’t have a reputation as a basketball power before that,” says Charlie Titus, a former star guard for Boston Tech and the current head coach at UMass Boston. “We hadn’t consistently produced players like they had in D.C. or New York.”

Ken Hudson wanted to change that dynamic. A small man with big accomplishments, Hudson was the first full-time African-American NBA referee, an executive with Coca-Cola, and general manager of the late, great WILD-AM radio station. To showcase Gaskins and the Boston Six, in June 1972 Hudson organized what became the premier high school basketball tournament in the country, the Boston Shootout, an opportunity for the Boston Six to represent their city and face off against the nation’s best players: Connecticut baller Walter Luckett, New England’s all-time leading scorer, who was hyped on the cover of the November 27, 1972 Sports Illustrated; Phil Sellers, a Brooklyn bruiser who later led Rutgers to its only Final Four appearance ever; and Adrian Dantley from D.C., an unstoppable and unorthodox forward who went on to make the Hall of Fame.

“I felt like we were the underdogs,” Smith tells the Dig all these years later. “It seemed like everybody was talking about Luckett and Sellers and Dantley.” Bijan Bayne, an author and historian, says, “People thought Boston was just the host of the shootout.”

As General Manager at WILD, Hudson had a megaphone for local promotion. “WILD blasted us throughout the city for two weeks before the tournament,” Smith says. “Case Gym at BU was packed. The community really came out to root for us.”

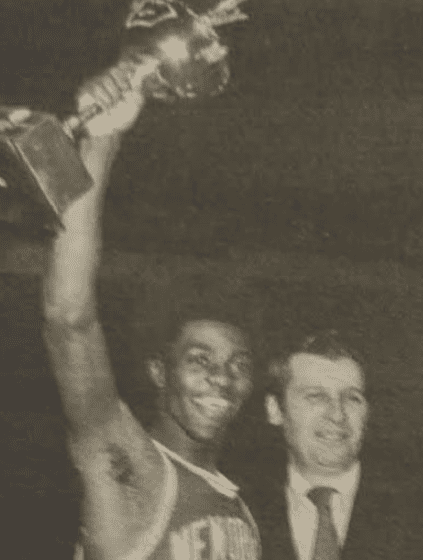

In the first game, Boston bested New York by a single bucket, winning 93-91 and advancing to play the Connecticut team for the crown. It was a momentous event; at halftime during the final, the WILD announcer relayed news that activist Angela Davis was acquitted of murder charges in California, spurring the crowd to cheer for revolution and the home team in the second half. On the court, Carlton Smith played the hero, scoring the final four points and swatting a last-second game-saving shot as Boston won 72-71.

The Boston Shootout grew to become the premier high school tournament in the country for 27 years. NBA stars such as Kobe Bryant, Paul Pierce, Patrick Ewing, Antoine Walker, and dozens of others followed in the footsteps of Gaskins, who later on recalled his halcyon days wistfully: “Being part of the Boston Six was one of the high moments of my life,” he said. “Too bad it takes time and experience for one to appreciate things.”

Following high school, Gaskins followed his CM coach, Ron Perry, to the College of Holy Cross in Central Mass, where Perry had taken a job as the athletic director. If Perry’s stepping up from high school coach to AD at a Division 1 school was dramatic, so was his player’s choice of Holy Cross over more established programs like Notre Dame and USC. “It may be the best piece of news the people of Worcester have had in a long, long time,” Gammons wrote in the Globe.

“I think the reason he ended up at Holy Cross was because of his relationship with Ron Perry Sr.,” Titus says. “He thought going to Holy Cross was the right thing to do and he could carry them into the national spotlight.” In any case, Gaskins had little help on the court. In a season in which his undersized teammates dropped passes and blew wins late in the game, the King himself seemed to run out of steam. In his first five games, Gaskins averaged 19 points and eight assists; nevertheless, Holy Cross lost a string of heartbreakers and Gaskins, not accustomed to losing, became increasingly frustrated. After he scored 21 points in one win halfway through his freshman season, Gaskins vented his frustrations in the locker room. “Basketball isn’t fun anymore and it used to be my whole life,” he told one reporter.

The dust-up attracted notice from that week’s Sports Illustrated, which ran a short item on the All-American’s clash with the system. Stuck on a losing team, Gaskins started to falter. He averaged 14 points and five assists per game—enough to lead the team, but at nine wins and 17 losses, the season was a total failure. “I had just gotten in with the wrong people at Holy Cross,” Gaskins told Gammons. “Maybe because it was my first time away from home. I don’t know.”

Two months after basketball season ended, Gaskins was arrested for breaking and entering a dormitory room. With academic and disciplinary trouble on that front, he then transferred to Mitchell Junior College in New London, Connecticut, with plans to improve his grades and return to Holy Cross. He explained the slip to Gammons: “I had been there a while and this kid Larry, who had been at the Cross and then left, was living nearby and called me. Larry was kinda strung out at the time and he told me he had to get some money. I said no, but he convinced me, this one thing was so small and no one would ever know. We’d never get caught … I really hurt the people who were best to me. Mr. Perry, through high school and onto Holy Cross, was the man I most admired. He was like a father to me.”

Another arrest—this one apparently due to racial profiling, as he was charged with carrying a screwdriver in a white part of Cambridge—put an end to any hope of a Holy Cross comeback. Things only got worse when, a few months later, Gaskins’s older brother was found dead, riddled with more than 100 bullets. “The facts are still unknown,” Gaskins said years later. “He was murdered and it was a big strain on the family. It was a critical time for all of us.”

Still nursing hoop dreams, Gaskins enrolled in Iowa Lakes Community College in Estherville, Iowa, where he lived in student housing—a trailer—and watched the grass grow while dominating the best junior college opposition in the country. He played well enough to lure big-time recruiters, and was courted by major programs in California and Kansas, but Gaskins wanted to return home, and so in 1976 he committed to Boston College. It was to be a reunion for four of the Boston Six, with Gaskins joining his old teammates Collins, Smith, and Carrington. The relationship never materialized though, and Gaskins told Gammons that he never heard directly from BC why they chose not to enroll him. “I think the dream was still with me until then,” he said to the reporter.

“That kinda took it out of me. Really depressed me for a while. I really would have liked to have played with Billy, Bobby, and Wilfred. Remember the Boston Six?”

ACTION GASKINS

It wasn’t long until the Boston Six slipped deep into the city’s memory. Three made the NBA, with only Ron Lee sticking around for any significant amount of time. “I think we let a lot of people down,” says Smith, whose career ended after four years of college ball in Rhode Island. “People in the community thought each one of us would make the NBA. I still get stopped by people and they say, ‘Who was the best of the Boston Six?’”

By the time that Gaskins met with Gammons in that downtown diner in 1976, his NBA dreams had faded, though the pressure to provide remained. “I’m the oldest male at home now I’ve got to help out. But I’m a risk. I kinda doubt anyone’s going to take that chance on me, and I’m not sure basketball is what I want,” he said. His passion had turned to working with children, and he soon had a job counseling teens who were under court supervision. “He was the favorite counselor,” his supervisor, Marian Young, told Gammons. “He’d be the one taking them to the courthouse and helping to straighten them out.”

In the early ’80s, after funding was cut for his job helping young people in Boston, Gaskins and his girlfriend moved to Santa Cruz, California. On the West Coast, he was considered royalty in exile, and his regal air made an immediate impact. “The word got out around town, ‘You got to meet King,’” says Paul O’Brien, a director at a Santa Cruz treatment facility, who hired Gaskins in 1981. Gaskins worked with addicts in recovery to help them rebuild their lives and move on. O’Brien continues: “He was a guy you’d notice. A tall, handsome, lanky, black guy in a beret strolling along with his own unique charisma. Immediately you knew he was a weird, interesting guy. King knew when people were holding back. He could share his own struggles and confront someone and encourage them to keep going even when things are bad and scary. He could tell people to enjoy life.”

In 1984, Gaskins began working with youth in Santa Cruz, eventually taking on a role at the YES School—an alternative program for kids trying to avoid drugs and alcohol. Reaching children in the midst of crisis, Gaskins drew on his own experiences to convey a sense of hope. “When King said, ‘I’ve been disappointed,’ you knew he meant it and he wasn’t blowing smoke,” says the school’s director Clare Wesley all these years later. “He was profoundly authentic, and he went into the streets to reach the kids who never made it through the door.”

Michael Watkins was the director of alternative education in Santa Cruz County—responsible for 800 high-risk students—and saw Gaskins in action. “I watched him in different arenas and realized his skill set could help our goals and I scooped him up. Like someone born to play basketball, King was born to counsel.”

It’s also said that Gaskins changed Santa Cruz beyond the classrooms. The community had a sizable Hispanic population but few African Americans—and almost no people of color in leadership positions in the 1990s. “King was a trailblazer and leader in Santa Cruz,” Watkins says. “He was a bridge builder for a homogeneous community becoming a diverse community.”

Gaskins confronted the community’s threats head on—even when it came in the form of infamous street gangs. By the early ’90s, the rivalry between the Mexican Mafia and La Nuestra Familia was heating up as local ranks swelled and the drug market fueled a rise in violence. Gaskins came to the aid of a town living in fear. “King brought the gangs together to promote peace and relieve the tension in the community, and it had a noticeable effect,” says Watkins. “He worked hard to reach the White Pride gangs too. The King Gaskins persona was big and it was real.”

On strolls along the boardwalk in Santa Cruz, Gaskins was often stopped by an endless stream of students and friends. He was quick to rave about his joys in life—especially fatherhood. Shortly after moving to California, Gaskins met Michele Baime, and the couple lived together for more than 10 years. In that time, Gaskins helped to raise Baime’s children, and told friends he loved being a dad. “I am proud to tell the world he is my father,” says his daughter Amy Hecht. “My father gave me the greatest gift anyone could give to another person; he believed in me.”

Gaskins also believed in the most vulnerable among us. Take Jason Murphy-Pedulla, who at 16 was addicted to crack cocaine and facing eight years in youth prison. Coming from a home with two addicted parents, Murphy-Pedulla was an angry young man ordered to attend the YES by the courts. “I felt unreachable, unseen, unheard. I’d been conditioned to be racist and prejudiced and to not trust adults. I tried to push King away but he didn’t waiver. He shared his own struggles, his own demons. He always said, ‘Keep going.’”

In June 1994, on a camping trip with his students, a 40-year-old King Gaskins drowned while swimming in the ocean. His student-turned-colleague Murphy-Pedulla recalls: “When he died, I made a commitment to carry on his legacy. The things he said stuck with me and I became a psychotherapist, wrote a book. I’ve tried to keep at it as a way to honor King.”

People honored Gaskins throughout Santa Cruz. The guys he played streetball with at Jade Street Park named him “The Peacemaker” for his ability to mediate on-court feuds. Now they put up a gold plaque with an excerpt from the Bible verse Matthew 5:9: “Blessed be the peacemakers for they will be the children of god.” Students of his also painted a mural of Gaskins smiling over Pacific Avenue in the heart of downtown. Last June, 20 years after his death, hundreds of people gathered to restore it using paint said to last a century.

In Boston, there are no murals or public displays for King Gaskins. He exists in the city’s collective memory though, his smooth pull-up jump shot forever cherished by old ballplayers, coaches, and sportswriters. Even into the early ’90s, Gaskins was still known to show up and play pickup games around the Hub when he was home visiting family, says Bayne, the basketball historian. Because he was almost 40, younger players were watching Gaskins for weakness.

“My friend had played college ball at Suffolk and was in his twenties,” Bayne says. “He said King Gaskins was still impressive, still athletic and strong.”

George is a Boston-based writer and the author of "Gangsters of Boston."