Experiments in co-operative economics started in the colonial era

Sometimes I despair over the lack of social imagination in contemporary America. No matter how much we complain about the obscene and widening gap in income and wealth between the super rich and everyone else, we seem unable to imagine a society based on principles other than the ones that dominate our own: individual self-interest; cut-throat competition for jobs, status, money, and power; the desire for unlimited consumption; and the pursuit of profit as an end in itself. It wasn’t always so. In order to remind myself of that fact, I collect books, magazines, newspapers, and pamphlets from the alternative movements and social experiments of America’s past.

I recently took a close look at a copy of a newspaper in my collection dated June 7, 1877, called the American Socialist. It was published by those involved in the famous and unusually successful experiment in communal living, common ownership, and cooperative work at Oneida, New York. An article on the front page of the paper, titled “Co-operation in Massachusetts,” is an excerpt from the eighth annual report, published in Boston, by the Commonwealth’s Bureau of Statistics of Labor. The report describes a surge since 1840 in attempts to establish a “system of Co-operation, especially in the distribution of goods” (more or less like the Oneida community, minus its controversial practice of “complex marriage,” i.e., polygamy and polyandry). The report goes on to connect this recent development with the original Massachusetts Bay Colony. Its author writes:

“Massachusetts, from her earliest settlement, ingrafted into her theory, practice and law the fundamental principles of Co-operative control. Her chief corner-stone is laid upon the enduring basis of equality of right, equity of dealing, unity of purpose…

“In the year 1620 nothing was known of the subdivisions of labor, nothing of machinery as at present understood. The home was the manufactory, the members of the family were the weavers, tailors and dressmakers. The carpenter and the shoemaker were at their door, needing but few tools, and those were easily made by their neighbor, the blacksmith. …

“The first industry that demanded congregation of labor and aggregation of wealth was the fisheries; and here the Pilgrim completed the circle of his possibilities. These men, united in motive, method, and purpose, found mutual help the best self-help; found that equity in risk, responsibility, and profit, like honesty, was the best policy, as well as in unison with good morals and the previously formed habits of mutual government.

“The share system in the cod and mackerel fisheries was the first introduction of co-operation in industry, as the establishment of the township on the congregational principle was the inauguration of republican government. Here in this Commonwealth was planted by the Pilgrims the germ of co-operative enterprise.”

Although the author of the report does not mention him, the Pilgrim John Winthrop comes to mind. While still aboard a ship on its way from England to the Bay Colony, he articulated his celebrated vision of the future, that of a “Shining City upon a Hill.” Ronald Reagan, who appropriated the theme in his presidential campaign of 1980, radically misunderstood or misrepresented it. Unlike Reagan, Winthrop was no champion of unfettered capitalism. According to him, in that shining city, “the rich should not eat up the poor,” and “every man might have need of others, and from hence they might be all knit more nearly together in the bonds of brotherly affection.” The city, of course, was Boston, and, in the vision of Winthrop, it was intended to be the capital of what we could call a socialist commonwealth. Even though his later actions against Native Americans and holding of captured Pequot combatants as slaves did not square with that vision.

The word “socialism” did not exist in the 1600s. It was invented in England in the early 1830s as a synonym for “cooperativism.” The word was applied initially to the writings of the Englishman Robert Owen and the Frenchman Charles Fourier who inspired and, in Owen’s case, directly financed many of the cooperative experiments to which the report of the Bureau of Statistics of Labor alludes.

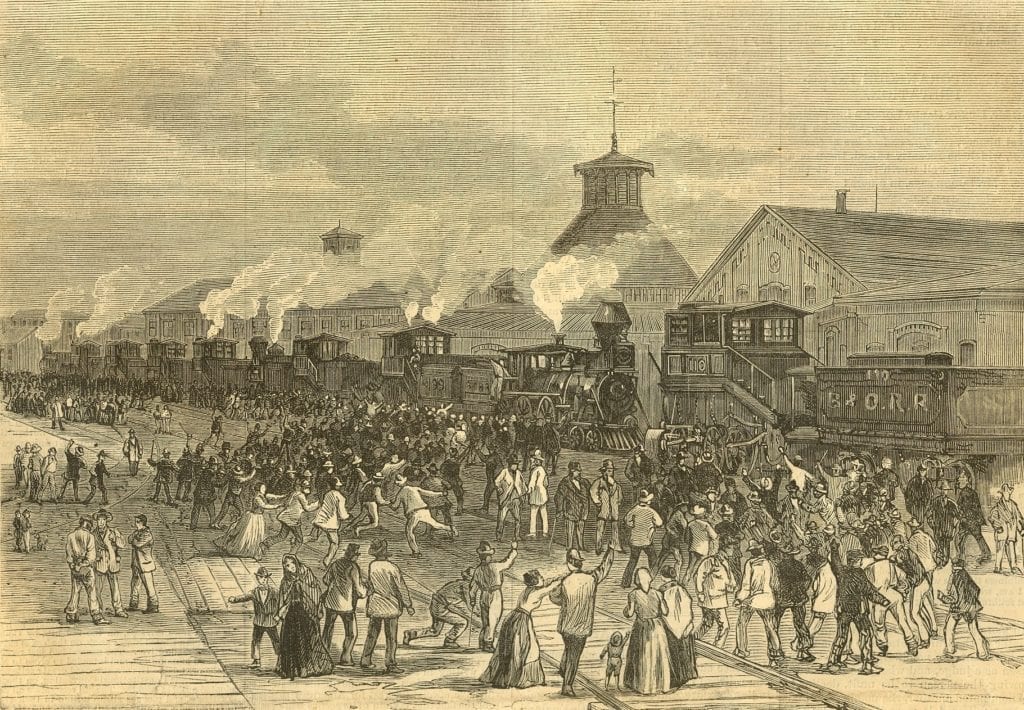

A great deal had changed between 1620 and the late 1800s when the government report was written. The country won its independence from England, of course. Closer to 1877, the Civil War resulted in both the abolition of slavery and the domination of the United States by the industrial capitalists of the North, a good number of whom owned factories in Massachusetts. Massive immigration was on its way to altering substantially the ethnic composition of the US population, especially its working class. Super-exploited industrial workers were starting to organize labor unions that would wield the strike weapon in order to improve their collective conditions of life. The suffragette movement that ultimately won the vote for women in 1920 was also in its early stages. During their best moments, the socialist developments of the early 20th century would take all of this into account. A dramatic example is the 1912 Bread and Roses strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts, led by the revolutionary socialist union the Industrial Workers of the World. The multiethnic textile workers of Lawrence walked off the job in response to a cut in pay, with the militant participation of large numbers of women who worked in the factories.

What connects the Bay Colony of the 1600s, the cooperative experiments of the 1800s, and the labor and socialist movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, in spite of the deep-going changes the Commonwealth experienced over the course of three centuries? It is the basic values they share. In the words I have already quoted, these values include the embrace of “co-operation” over competition, “mutual help” over the pursuit of narrow self-interest, “brotherly” (and sisterly) solidarity over acquisitive individualism, and the adamant refusal to allow “the rich to eat up the poor.”

In my more pessimistic moments, I remind myself that, while these values may be sleeping, they are not dead. They are only waiting for enough people to awaken them so they can play their indispensable, transformative role once again.

Gary Zabel is a retired UMass Boston philosophy professor.

Gary Zabel is a retired philosophy professor.