Film Review: Still Processing

Directed and co-edited by Sophy Romvari. Canada, 2020, 17 minutes.

Available with subscription on MUBI.

The way a film camera works is that the lens opens for just long enough to let the light reflecting off whatever you’re photographing enter the lens and burn an image on the emulsion coating the film in the camera. That chemical record is used to create a negative, which then can be used to create prints. In other words: when you photograph a person, what you create—before the image itself even—is a record of the light that touched them in that very moment. That light becomes the photograph, becomes a way of accessing what remains of the radiant instant of chemical reaction.

With the process of photography in mind, the title of Sophy Romvari’s Still Processing is a particularly sober pun. Romvari has three brothers, two of whom died prior to the short’s production. Still Processing depicts Romvari’s examination of a box full of old family photographs, film negatives, and home movies, and it’s clear that what’s processed here is not just the trauma of these losses but additionally the physical act of “processing” film. For Romvari, the two are analogous; image recalls memory as the work of reproducing an image recalls the work of remembering what has been lost.

What’s remarkable about Still Processing is that it’s a film like a letter: singular in nature, and with a lingering intimacy that gives you the sense that it was only ever meant for the recipient. A sense of near voyeurism creeps in as we see Romvari looking through boxes of photographs, examining reels of family photos, and then weeping, having a panic attack. Outside of a bookending voiceover where Romvari reads a letter from her parents that came with the box, her direct addresses to the audience are made through subtitles at the bottom of the frame—the first flash of text on the screen explains it by stating “There are some things that cannot be said out loud.”

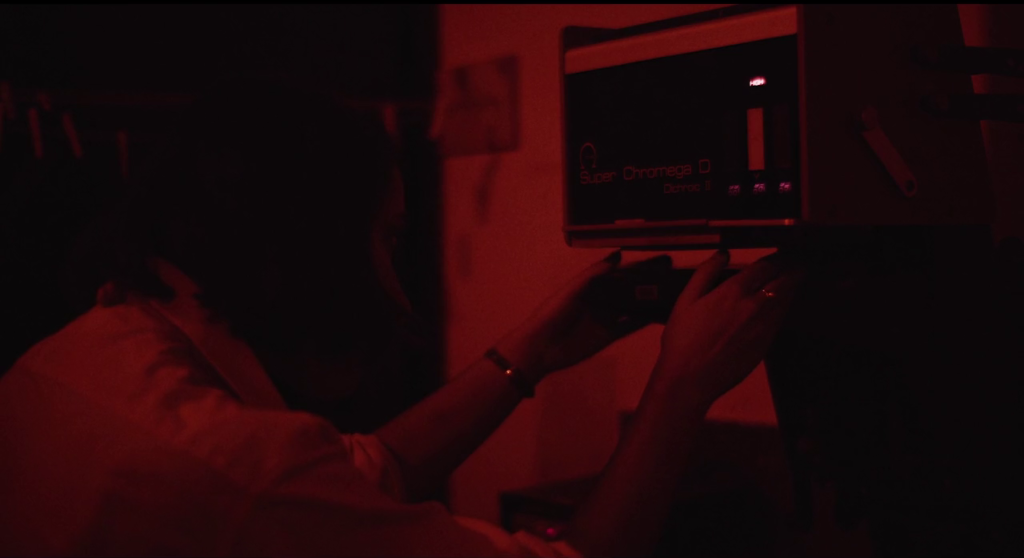

Romvari is clearly interested in the unsaid, which here manifests entirely through image—a medium that forgoes the vagaries between the said and unsaid for the remoteness of a fixed moment. There are many striking compositions of Romvari in blood-red dark rooms, looming over developer baths or illuminated from below by the ghost light of a lightbox. It’s simultaneously a space of clinical—almost scientific—expertise, and a haunted, embryonic zone where we find our past resurfacing through clear chemical pools. Memory in this film straddles these lines too, between the matter-of-fact (asking a sibling “how old were you in this photo?”) and the haunted (images emerging unbidden as you try to sleep).

The film ends with a slideshow of these photos, set to a soft cover of Simon & Garfunkel—which sounds like it could be too sentimental or obvious. But when it arrived, I thought of those original traces of light. Passed down as family heirlooms, handled with care, restored by Romvari, and now preserved in the gleaming frame of her film, the distance between us and those traces has never been more acute. Or, I think, more hopelessly loved. [★★★★★]