“The cry of our enemies was dreadful, especially when our men ran out to recover their arms.”

This article was originally published in the Dig in 2020. It’s a great holiday feature, and you can expect us to trot it out every year around this time from now on. Enjoy …

About 400 years ago, the so-called Pilgrims came to Massachusetts, made friends with the natives, learned to farm, and held the first Thanksgiving—or at least that is the Hallmark Channel version of events most people are familiar with.

What is often left out, besides but certainly related to the genocidal chapters of the story, is how firearms and idiocy helped shape this pivotal historical event.

After surviving the trip across the Atlantic Ocean, the Pilgrims docked their ship off the coast of what is now Provincetown so that a smaller crew of about a dozen could scout the bay and find a proper landing in what would become Plymouth. Roughly 100 passengers were left to wait on board.

The scout crew had its first interaction with Native Americans in what is now Eastham, on Cape Cod. After camping near the beach for the night, two of the men decided to randomly test their muskets to make sure they still worked. It was December, and early in the morning, so it was probably still dark outside.

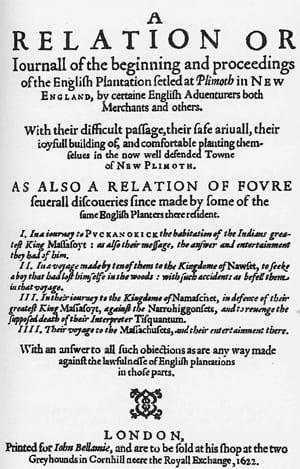

“About five o’clock in the morning we began to be stirring, and two or three which doubted whether their pieces would go off or not made trial of them, and shot them off, but thought nothing at all,” wrote Edward Winslow in Mourt’s Relation, which is one of two primary accounts of the first few years of the Plymouth colony.

Shortly after, while the group was preparing for breakfast, one of the men, who had been exploring over a hill, came running back shouting about “Indians.” Miles Standish pulled out his snaphance, which was a gun with a flintlock, while the rest of the men were armed with muskets that required lighting a wick to fire.

The entire account presents the Pilgrims like warriors out of a Michael Bay flick, including one hardcore Pilgrim who grabbed a burning log and hoisted it over his shoulder so that the other warriors could light their muskets on the flame. It’s a hero’s tale written by the protagonists if there ever was one:

One took a log out of the fire on his shoulder and went and carried it unto them, which was thought did not a little discourage our enemies. The cry of our enemies was dreadful, especially when our men ran out to recover their arms; their note was after this manner, “Woach woach ha ha hach woach.” Our men were no sooner come to their arms, but the enemy was ready to assault them.

When the dust settled, the Pilgrims reported that for all of the “combat,” there weren’t any bodies found.

Meanwhile, the passengers of the Mayflower narrowly survived disaster while waiting on the scout crew when a teenager almost burned down the ship while playing with his father’s gun next to an open barrel of gunpowder in one of the ship’s cabins. “Through God’s Mercy, escaped a great danger by the foolishness of a boy,” Winslow wrote.

Despite what was either a tactical victory back on the beach or the natives backing away from freaked out, trigger-happy Europeans, the Pilgrims were eventually able to make an uneasy agreement with the local Wampanoags, with tribal leaders including Chief Massasoit who were willing to align with the gun-loving Europeans as protection against the rival Narragansetts, according to Mourt’s Relation.

Despite what was either a tactical victory back on the beach or the natives backing away from freaked out, trigger-happy Europeans, the Pilgrims were eventually able to make an uneasy agreement with the local Wampanoags, with tribal leaders including Chief Massasoit who were willing to align with the gun-loving Europeans as protection against the rival Narragansetts, according to Mourt’s Relation.

“He has a potent adversary in the Narragansetts, that are at war with him, against whom he thinks we may be of some strength to him, for our pieces are terrible to them,” Winslow wrote.

As George Washington University scholar David J. Silverman wrote in the Atlantic last year, there is a critical background to this story: “Contrary to the Thanksgiving myth … friendliness does not account for the alliance the Wampanoag tribe made with the nascent Plymouth settlement. The Wampanoags had an internal politics all their own; its dynamics had been shaped by many years of tense interaction with Europeans, and by deadly plagues that ravaged the tribe’s home region as the pace of English exploration accelerated.” In piecing these stories together now, Silverman adds, it is “important to acknowledge that Wampanoag perspectives are distorted or selectively represented in the historical record,” but also realize they are not absent. “However imperfectly, those same sources also shine light on how these events looked to the Wampanoags.” For example, the Pilgrims were gun nuts.

There are only two brief accounts of the first Thanksgiving meal in primary historical sources, and neither indicate that Pilgrims originally invited the Wampanoag natives to join them. William Bradford wrote about the bounty of the harvest in Of Plimoth Plantation, while Winslow covered the festivities in Mount’s Relation. According to those accounts, the Pilgrims held a week-long party to celebrate their first successful harvest, which meant they would not starve to death over the winter. Aside from feasting, the only activity that was described was “practicing at arms,” which meant that they were playing with guns and shooting targets.

“At which time amongst other Recreations, we exercised our Armes, many of the Indians coming amongst us,” Winslow wrote.

At the time, the Wampanoags were still recognizing their mutual-protection pact with the Europeans, so it was probably not shocking when 90 of their warriors showed up after hearing the morning gun fire. Once they saw that the noise was the result of firearm foolishness, the natives sent out some of their own to bring back a few deers to share in the feast.

Some historical accounts still show that the first Thanksgiving was a diplomatic summit. In reality, it was probably more like a nervous reprieve from potentially devastating violence. That kind of horror was still about 15 years away.

Zack is a veteran reporter. He writes for DigBoston and VICE, and formerly reported for the Boston Courant and Bulletin Newspapers.