As droughts and climate change impact their food supply, more furry friends are being spotted closer to cities in Massachusetts

Yes, that may have actually been a black bear you saw—in the suburbs!

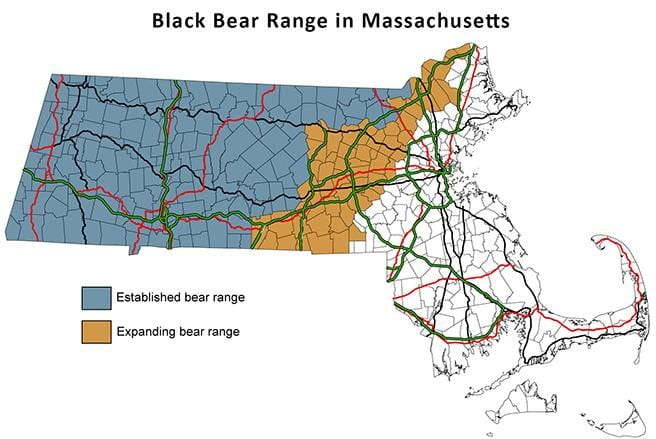

The 300-pound animals have been increasingly spotted east of I-495, even in urban areas, a consequence of a growing bear population combined with the impact of climate change cascading throughout the Northeast.

Historically, Massachusetts counted few black bears within its borders, largely due to rampant hunting and European settlers turning natural habitats into farmland. Over the past century, as wildlife conservation efforts came along with the move away from agriculture and into the industrial revolution, their numbers have hit an estimated 4,500 (mostly concentrated in the Berkshires, west of the Connecticut River).

Bears themselves can easily adapt to rising temperatures, said a researcher at MassWildlife, the state agency responsible for conservation. Still, changes in weather can impact the availability of natural food sources in rural areas.

“Black bears are found in Florida, they’re found in Louisiana. They can adapt to a wide range of climatic conditions,” said David Wattles, black bear biologist and researcher at MassWildlife. “Where a bear would be affected is if some of the plants in the Northeast can’t cope with hotter temperatures.”

If the plants and berries they rely on to eat can’t withstand the climate and extended periods of drought, Wattles added, bears could travel to other places, including urban areas, in search of food sources. And as climate change increases the frequency of severe droughts, they may travel outside of their usual comfort zone.

Over the summer, the Northeast saw one of the harshest droughts in years. Even now, there are critical drought conditions in most of northeast, central, and western Mass, according to the state’s Drought Management Taskforce. Similar shortages occurred in 2016 and 2017.

Meanwhile, residents have so far reported sightings in Worcester, Lowell, and Peobody this year, according to a database kept by the UMass Amherst MassBears project, which compiles submissions of sightings from members of the community.

In 2021, MassBears reported two black bear sightings in Waltham, alarmingly close to metropolitan Cambridge. (The rumor was that they were looking to enroll at Harvard; we tried reaching out for comment, but the bears were unresponsive.)

Now, as summer turns to fall, black bears are preparing for their yearly hibernation, increasing their caloric intake with a regular diet of berries, nuts, and roots through autumn. Once that period ends after about seven months, they will go back out in search of food again—but due to changes in temperature and weather influencing plant growth rates, they may find less available food than the last time they left their dens.

“The bears, and every animal and ecosystem, is really dependent on all the plants, whether those be the berries, the nuts, the roots,” said Zac Watson, a MassBears researcher and junior at UMass Amherst. “The reliability on these food sources, it’s going into a little bit of a question.”

With inconclusive data, it’s hard to say exactly how weather patterns and hibernation periods might change, said Elizabeth Zhang, a MassBears researcher and UMass Amherst junior. According to the MassWildlife Climate Action Tool, a resource mapping how climate change can impact local wildlife, milder winters might reduce the length of time bears spend in hibernation.

“Increased bear activity combined with the potential for low food availability during winter months may increase the potential for human-bear conflict, as bears are more likely to visit urbanized areas in search of food during shortages,” reads the entry on black bears.

In urban areas, food is usually more abundant. Trash bins and scraps left in front of houses are a full meal for a hungry bear.

“People really need to understand that if they have bird feeders out, they are essentially training bears to come to their backyard, to come to their deck to look for food,” Wattles said. “If their garbage is just left out on the side of the garage, or left out a week, or there’s a dumpster overflowing, that’s a buffet for a bear.”

Bears are “opportunistic omnivores,” Zhang said. They’re mostly harmless, and won’t actively hunt. Wave your arms around and make a lot of noise and a black bear will often get scared and book it.

At the same time, black bears won’t shy away from breaking a few eggs to make the proverbial omelet—or from eating the chicken whole. MassWildlife has reported an increase in the number of incidents in which black bears break into backyard coops and eat chickens. According to a statement from the agency, it’s rapidly becoming “the number one human bear conflict in Massachusetts.”

“It’s just like a food source literally packaged up beautifully for them,” Watson said. “They can go in there and grab it. The chickens can’t really escape.”

The state recommends for residents who keep chickens in their backyard to set up an electric fence. Given enough time and a couple shocks, black bears can be shocked into staying away.

But presently, residents or travelers in eastern parts of the state who are unfamiliar with black bears will often be unsure of how to proceed when they spot one, Wattles said. Between MassWildlife, the state’s Environmental Police, Animal Control, and local police, authorities receive innumerable calls related to black bear sightings, Wattles said.

In their part, much of the work that MassWildlife and Wattles do centers on education, he said. The mere presence of a black bear isn’t a threat to public safety—unless backyard chickens count as the public. Most times, Wattles noted, the standard response to a report of a black bear sighting is to leave it alone.

“People are experiencing conflict with the bear, they often ask us to relocate it and the answer to that is always no,” Wattles said.

One of the few exceptions is if a bear is reported to be near traffic. If a bear is left alone downtown, Wattles said as an example, it could lead to a vehicle collision. He estimated 35-50 bears die in Mass every year due to vehicle crashes.

Looking forward, Zhang and Watson said policymakers need robust data on black bears in the state to make informed decisions. In the meantime, MassBears is creating a robust population-density model, mostly relying on crowdsourced submissions from members of the community who can report sightings on their website.

“Submissions allow us to really build these robust models that help us make very informed decisions at the management level,” Zhang said.

Wattles urged residents to learn best practices for living with black bears, as opposed to blaming them for dining at the buffets they stumble onto.

“People often think that these are bad bears that are getting into a bird feeder or getting into a chicken coop. It’s every single bear,” Wattles said. “It really is up to individuals and communities to take that messaging seriously.

“We really can peacefully coexist with these animals.”

Jesús is a reporting intern for DigBoston and he’s wondering if he could ask you a few questions for a story he’s working on. Follow him on Twitter @jmarrerosuarez.