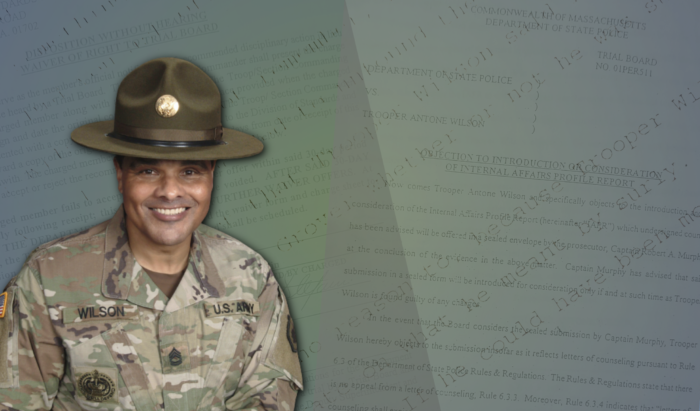

The story of a former Massachusetts statie whose career was “submarined”—told here 20 years later—reflects the struggles progressive and Black cops still face in a corrupt department that eschews reform

After tweaking, editing, and adding to this project for several months, I finally decided to publish my never-ending saga about the Mass State Police. It is far from a work of traditional reporting; rather, it’s become more of a perpetually developing book, and one that the main subject, Antone Wilson, has played a significant role in informing, along with dozens of corroborating and complementary sources, human and archival alike.

In the process of communicating with Wilson about earlier versions for fact-checking purposes, he provided me with several hundred pages of his own personal testimony that tell his side of the story. Excerpts from those writings are included herein as direct quotations, with many of his points countering the narrative established by official reports from two decades ago that omitted Wilson’s voice and perspective.

Since he was so forthcoming, and since I wanted to include additional points that Wilson and I deemed important but which fell beyond the immediate scope of my article, I also included an epilogue which I edited for clarity, but that is presented entirely in his own words. When you reach that point in the story, you will find it marked accordingly.

Finally, though he helped with many details, which our team checked against state documents and other sources in cases where it was possible, Wilson had no editorial oversight of this reporting. With that said, I am comfortable saying that I believe he is telling the truth, and my hope is for his story, basically unknown until now, to be presented clearly and made available for all to read online forever after. -CF

At around 1:30 am on a Thursday in late November 1999, then-Massachusetts State Trooper Antone Wilson pulled over a diminutive Toyota Echo on Commonwealth Ave in Boston. Beside his boatish cruiser, the concept auto was a golf cart.

Wilson didn’t know it at the time, but the interaction was being recorded for a major news outlet.

“How ah yah?” Wilson asked the passenger, Harvard student Dan Lienert. “Is this car gas or electric?”

It turned out Lienert was test-driving the buggy for a marketing gig, rolling it around the region “seeking the opinions of other students.” As part of the campaign, he chronicled his travels in the New York Times, and in the dispatch acknowledged the tree-hugging trooper who stopped him to ask about fuel efficiency.

“Sure, police officers might flag down a Plymouth Prowler for a closer look,” Lienert wrote in the Times. “But why would they even notice an entry-level Toyota like this two-door Echo, a car that shares subcompact status with nearly invisible appliances like the Hyundai Accent?”

“Most cops are conservative,” Wilson explains. A senior drill sergeant in the US Army Reserve, these days he works as a private security contractor with top secret government clearance. Two decades after his statie career was cut short for reasons beyond his control, he recalls the hostility he felt from fellow troopers due to his liberal leanings during his time on the force.

“Let’s just say I wasn’t liked,” Wilson says.

Wilson emailed me for the first time nearly two years ago. He’d read a series that I published with my team from the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism about chronic Massachusetts State Police (MSP) abuses. Among other offenses, we flagged the department for over-spending on guns and artillery, and revealed a lobbying scheme that resulted in the questionable procurement of millions of dollars worth of Tasers. It was one of multiple apparent rackets involving Dana Pullman, a high-profile trooper who headed the State Police Association of Massachusetts (SPAM) until he was indicted on federal charges including fraud, racketeering, and tax crimes in 2019. In the months that followed, I received more emails than usual from people with knowledge of MSP subterfuge.

From there, I contacted some chatty current and former state troopers to ask if they recall hearing stories about Wilson. Though most were foggy on the details of his departure, the consensus suggested that he is one of many Black and brown cops whose aspirations were crushed by the MSP’s vicious bureaucracy. With his credibility checking out, after reviewing Wilson’s paper trail of lawsuits stemming from his ouster, I sensed that there was something worth exploring. Following some email correspondence, we agreed to meet at a cafe in the South End on a Saturday more than a year ago (before the COVID-19 pandemic and the wave of protests spurred by the killing of George Floyd by a white cop in Minneapolis last May). I still wasn’t committed to the story though, so I planned it for less than 60 minutes before closing time, in case I needed an excuse to extract myself.

Our first exchange only lasted for one cup of coffee. I sipped, and Wilson abstained from any sweets or caffeine, sitting on a backless stool with his frame piped at 90-degree angles, the creases on his fatigues starched for roll call. He jogged through the events that fomented his fallout with the State Police, and told me about growing up in MetroWest around the same time as Pullman, who just a few weeks earlier had become the poster boy for crooked cops in the Commonwealth. I considered the juxtaposition of their journeys, and through my dark roast it became extremely clear that the injustices Wilson endured speak to a question I have contemplated endlessly: Why don’t more ex-cops expose the unbelievable corruption that decimates resources and leaves residents less safe than they ought to be?

Wilson, who is of Cape Verdean background, says he’s disinterested in addressing institutional problems, and is focused on himself. “I’m not going to paint the whole [MSP] as racist,” he told me, “even though they mostly are.” Yet while his experience is an outlier in many ways, it also serves as a case study in how and why Mass has a dearth of people of color working as cops, particularly in the upper ranks.

According to US Census Bureau data, 65.5% of police officers in the US are white (non-Hispanic). Black (non-Hispanic) is the second most common race or ethnicity, representing 12.8% of officers. Per 2018 data, that number exceeds the Black (non-Hispanic) share of the overall population, which is 11.7%.

MSP did not respond to a request for current head counts. But the most recent diversity numbers in official reports and media mentions are dismal. As Boston Globe reporter Matt Rocheleau put it in 2019, “How do you improve diversity and equity at the Massachusetts State Police, where eight in 10 troopers are white men, no minorities hold high-ranking positions, and numerous discrimination complaints have been filed?” When the same newspaper of record visited the topic of hostile treatment of women and minorities in the department two years earlier, fewer than 12% of troopers were people of color.

Antone Wilson was not one of them. By that time, he was long gone.

Though he would eventually go on to earn two master’s degrees and become a drill sergeant, Wilson calls his early academic record “terrible,” and says his SAT scores were less than 1,000 combined. After he graduated from Natick High School in 1979, Wilson’s father, a laborer, pulled some strings and nearly fixed a chance for him to attend Boston College through a minority feeder program. But after that plan was thwarted by a Black administrator at BC who Wilson says determined he was hardly worthy of one of the designated spots for exceptional students of color, his mother reached out to admissions officers at Howard University, the historically Black college in Washington, DC, where she wanted him to attend in the first place.

“That’s what a lazy, rotten, no-good kid I was,” Wilson says in retrospect. “I didn’t do anything for myself. I let other people do it for me. That’s the way I was back then.”

Howard admissions gave Wilson a chance, provided he took college courses beforehand and maintained at least a 3.0 grade point average. He slugged along there for three years, but says he couldn’t focus enough to go the distance. “I majored in journalism because Richie Cunningham majored in journalism on Happy Days.”

In his final year at Howard, Wilson pledged the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, but says that after six months of “getting my ass beat,” he dropped out of the process and left campus in shame. An attempt to rebound by joining the Air National Guard didn’t pan out either; after less than a month of training, recruiters told Wilson that his hearing wasn’t sharp enough for his ground radio specialty.

Back in Natick, Wilson grew bored and unmotivated until two subtle but resonant road signs altered his course. First, he fell for a woman who was “out of [his] league.” To date her, he would need a solid job, or at least impressive prospects. Around the same time, in the summer of ’83, Wilson remembers driving one day on Route 30 in Framingham and becoming entranced by the projection of blue lights on an overpass.

“I looked on the [Mass] Pike and a trooper had someone pulled over. I said, That’s what I want to do, that’s what I am going to focus on.”

Things didn’t work out with the woman he was courting, but Wilson got on a track. He enrolled in criminal justice courses at Northeastern University in Boston, became EMT certified, and in 1984 even successfully pledged the Hub’s Sigma chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha that Martin Luther King Jr. joined during his tenure at Boston University in the ’50s. Planning ahead, Wilson also got in line to take the civil service exam with his sights set on becoming a cop. In the meantime, in 1985 he joined the Marine Reserves.

Things didn’t work out with the woman he was courting, but Wilson got on a track. He enrolled in criminal justice courses at Northeastern University in Boston, became EMT certified, and in 1984 even successfully pledged the Hub’s Sigma chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha that Martin Luther King Jr. joined during his tenure at Boston University in the ’50s. Planning ahead, Wilson also got in line to take the civil service exam with his sights set on becoming a cop. In the meantime, in 1985 he joined the Marine Reserves.

“The service wasn’t even on my radar [before college], though my dad always pushed it,” Wilson says. He also has uncles and cousins and a brother-in-law who served, and partially credits Wallace Houston Terry, a Howard journalism prof and African American reporter who wrote Bloods: An Oral History of the Vietnam War (an inspiration for the 1995 crime drama Dead Presidents), with energizing him to enlist. Wilson continues, “My family always said that some way, some time I should go into the military.”

In March 1986, Wilson excelled on the civil service test and was called up to the Metropolitan District Commission Police Department (MDC), which at the time was tasked with patrolling select roadways and reservoirs, and also assisted with everything from drug and SWAT ops to auto theft prevention. In retrospect, he says he was plugged in by a connected Northeastern professor who liked him. Whether the assistance helped or not, Wilson was qualified on paper to serve and protect—from his military and firearms training to emergency medical certification and swimming abilities that were required of Mets, as MDC officers were often called.

“The academy was easy for me. The academics were easy, the fitness was easy, the shooting—I excelled at all of that.”

He also liked his peers.

“Most of the kids who got in my class at the academy were either legacies or kids who were cops [in other Mass municipalities],” Wilson says. Not everybody had connections; like most of his fellow Black classmates, Lisa Butner came from outside of the system, and also wound up clashing with the department, in her case later suing over policies that prevented pregnant officers from driving department vehicles, interacting with the public, and working paid details. At the beginning, though, he says people mostly got along. Despite his subsequent frustrations, Wilson still smirks when thinking back on his training days. He continues: “My class was very talented—almost everyone had military, college, or police experience.”

Just six years into his MDC career, in 1992 the commission merged with the Division of State Police, the Registry of Motor Vehicles’ Law Enforcement Division, and the Capitol Police Department to become the singular Department of State Police we have today (commonly referred to as Massachusetts State Police). For Wilson and a lot of other Mets, the culture shift was shocking.

“Race wasn’t an issue [with the Mets],” he says. “But as soon as the merge happened, we picked up on it that race was an issue. There was definitely a resentment, and there was certainly a resentment toward our Black leaders.”

Wilson remembers thinking that the implementation of the merger was “haphazard.” “For a while, we were wearing State Police uniforms and driving MDC cars,” Wilson says and other former MDC cops confirm. “It was ridiculous. All the cars were beat to shit.”

The resentment MSP lifers had against MDC transfers was palpable.

“The State Police go through a military academy,” Wilson says. “They haze the shit out of them.”

Literally, as it turns out. In 2005, the commander of the MSP Academy was transferred after allegations surfaced that an instructor at their New Braintree facility shoved recruits’ heads into dirty toilet bowls, while another recruit was ordered to put on underwear that was soiled by a fellow classmate.

Wilson continues: “I don’t blame the State Police when they say there were elements of the other agencies that brought down the standards. After the merger, there were people who were wearing a State Police uniform who could have never made it through the training academy, and the State Police hated that.

“I know I could have done it because I was a Marine, but I was not the kind of Black guy the State Police like.”

By the time of the merger, Wilson was having serious reservations that he unabashedly wore on the sleeve of his blues.

“As I approached mid-career, I was more focused on my Army career and I was working toward a second bachelor’s degree in security. By that time my son was born, and I was also focused on him.

“I went my own way and never got involved in any agency events. I had no close friends in the organization. In a large police force, individualism like mine was suspect and your loyalty is questioned.

“I never cultivated any senior officer mentors because I had no interest in being an officer of rank. Once, a respected Black lieutenant suggested that, with my background, I should be studying for the sergeant’s exam. I told him that I had no interest in being a sergeant on the MSP, I wanted to be a sergeant major in the US Army.

“In retrospect, that was the wrong answer.”

At its founding and throughout much of its history, the MSP has been tasked with solving law-enforcement problems no one else in the state is equipped to handle. According to official statements, hallmark values of the institution include idealism, personal integrity, physical courage, and stamina. Another guiding principle has been exclusion if not outright white supremacy; though two African Americans served in State Police roles in the late 1800s, it wasn’t until 1956 that Samuel M. Range, a World War II veteran from Jamaica Plain, became the first Black member of the uniformed division of the State Police Patrol, as MSP was known at the time.

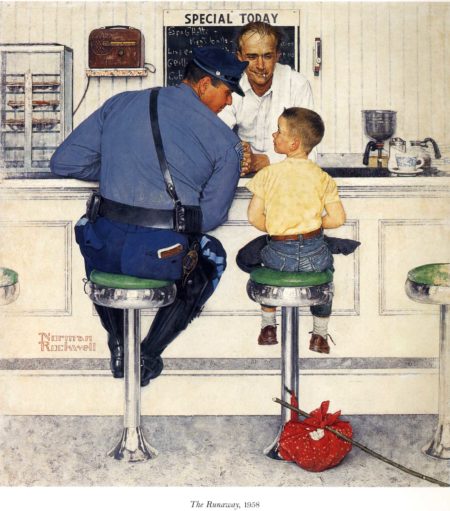

Founded at the end of the Civil War to enforce unpopular laws against the production and consumption of alcoholic beverages, the MSP is the oldest organization of its kind in the country. In 1921, the State Police became the nation’s first motorized statewide force, charged with protecting rural areas then being preyed upon by criminals made mobile by the automobile. From that time forward, membership in the department was highly competitive, and along with the Texas Rangers, MSP went on to help shape the mold for wholesome American crime fighting. Bolstering that eminence, the trooper depicted in Western Mass icon Norman Rockwell’s 1958 portrait “The Runaway” is former MSP Staff Sgt. Richard J. Clemens Jr., a neighbor of the artist who was on the force for five years when prints of his backside began appearing at soda fountains. He retired in 1975, but as the Springfield Republican explained in his obituary, Clemens Jr. remained “one of the most recognizable figures in the history of the state police” through his 2012 passing.

Rockwell’s benevolent protector is the protagonist in a narrative the MSP, as well as its officers’ union, SPAM, and Mass officials embrace even today as calls for reform grow louder and some other long-troubled departments reluctantly inch toward change. But that rosy plotline hasn’t reflected the real culture of the department in ages, if it ever did at all.

Rockwell’s benevolent protector is the protagonist in a narrative the MSP, as well as its officers’ union, SPAM, and Mass officials embrace even today as calls for reform grow louder and some other long-troubled departments reluctantly inch toward change. But that rosy plotline hasn’t reflected the real culture of the department in ages, if it ever did at all.

By one account of MSP operations that was commissioned by the state in 1996 and then slipped into a drawer and ignored until we found it in 2019, the legacy of upstanding heroes exemplar in which troopers take pride is a facade. Among the observations researchers highlighted: “Fairness and professionalism are organizational values receding into memory and institutional folklore.” Almost every criticism in the ’96 report could apply to the turbulence at all levels of the MSP today, but while the study was supposed to serve as a warning for troopers so they didn’t repeat the same tragic mistakes, the recommendations were ignored.

It was this environment in which Wilson found himself working among more than 500 other former Mets who, with no ceremony, plan, or welcoming committee, went to bed one night in 1992 as MDC cops and woke up the next day as state troopers. A range of factors fueled an inevitable culture clash; broadly, as Wilson and several law enforcement officers interviewed for this story explained, troopers were more buttoned up and military-minded, while most district commission cops, as one retired metro officer explained, “were street guys who actually walked a beat.” The 1996 report noted, “Lapses in training … reinforced … a fundamental difference between RTs (‘real troopers,’ in the words of those who graduated as recruits from the State Police Academy) and those who are not.”

Wilson remembers the dysfunction well: “Frankly it was cool to put the State Police uniform on. It’s sharp-looking and there’s more prestige. But as much as we did like the uniform, we wanted them to change the uniform, because we knew that as long as it was the same uniform, the State Police were going to say that they brought in this rabble [MDC police] and they disgraced the uniform. If we had all new everything, we could have had a super agency where everyone’s skills are utilized.”

By any measurable metric, the opposite happened instead. In microaggressive cases, skilled troopers were intentionally underutilized. On the most severe end of the spectrum, MSP working conditions have been hazardous. As one of many testaments to the continued negligence, in 2017 the Globe published an exposé showing minority and women troopers being subjected to “racial slurs and racist jokes, homophobic taunts, sexual advances, and lewd remarks—claims the state has paid hundreds of thousands of dollars to settle.”

Nowadays, even among the country’s most corrupt law enforcement agencies, MSP boasts various superlatives. From evidentiary transgressions ugly enough to fuel the recent Netflix doc How to Fix a Drug Scandal to winning a Golden Padlock award from the trade group Investigative Reporters and Editors for being the most secretive public agency in America, our troopers regularly summon national humiliating notoriety, all while landing on local five o’clock newscasts for any number of improprieties. Take your pick—in just the past few years, troopers have been caught plundering payroll, driving drunk, and in one case, allegedly shooting at an unarmed person in the middle of traffic on I-93. Recently, the department earned the ire of the public by allowing cops who were implicated in overtime theft to retire without criminal charges and with six-figure pensions. An Oct. 17 Globe headline read: “Dozens of State Police troopers remain on the force despite past illegal conduct.”

All sins considered, the divergent paths of Wilson and Pullman, the latter the embattled SPAM grand poobah, were predictable: the outsider, a Black cop, is jettisoned from the job. Along a similar timeline but on a parallel plane where different standards apply, a brash and corrupt white guy gets entangled in embarrassing shenanigans year after year and steals from his union in plain sight as he entertains a mistress on SPAM’s dime and collects “bribes and kickbacks,” and still becomes king.

Raised in MetroWest, Dana Pullman attended Kennedy Junior High School in Natick, where Wilson also went in the mid-’70s and even sat next to the future fellow trooper in eighth grade. From there, Pullman matriculated to Marian High, a since-closed co-ed school in Framingham where he played varsity hockey, and then went to college at UMass Lowell. In 1987, Pullman was sworn into the MSP as part of the 68th Recruit Training Troop, or RTT. A real trooper if there ever was one.

Before he blossomed to become the treasurer and then the president of one of the most powerful unions in Mass in 2012, in a position representing more than 1,500 troopers, Pullman hit some speed bumps on patrol. According to an internal memo obtained by the Worcester Telegram & Gazette in 2013, a department investigation from the early aughts found “sufficient evidence to prove that Trooper Pullman overlapped his scheduled work hours with hours that he worked paid details [and] worked in excess of 16½ hours in a 24-hour period without authorization on numerous occasions and failed to report paid details … in violation of an existing Departmental directive.” Furthermore, Pullman and another detail officer were “allowed to broker deals with construction companies for over-payments which raise ethical questions.” The other ethicist involved, Trooper Edward Bruso, retired in good standing in 2018 after more than 50 years of service.

The rap on Pullman is that he was only out for his own interests. Following his arrest in August 2019 on charges including “alleged embezzlement and misuse of SPAM funds for personal use,” Joseph Bonavolonta, the special agent in charge of the FBI’s Boston Field Division, called Pullman an “old-school mob boss,” and told USA Today he ran SPAM “like a criminal enterprise.” The agent said Pullman and Anne Lynch, the latter a SPAM lobbyist, “cheated and tried to obstruct our investigation at the expense of those hardworking troopers and taxpayers … Their actions were without a doubt disgraceful, underhanded and fueled by sheer greed.”

Perhaps greed was involved; as federal agents found, “Pullman used the SPAM debit card to pay for thousands of dollars of meals, flowers, travel, and gifts for an individual with whom Pullman was having a romantic relationship.” But while prosecutors focused on his selfishness, it’s nonetheless true that he genuinely looked out for the larger group. As one colleague wrote in a November 2015 edition of Trooper, the official publication of SPAM, touting his union’s president’s repudiation of civilian traffic flaggers: “Dana Pullman and this board are not only trying to find a fair way to close the pay gap, but are working to make sure that no more of our work is given away to groups that are inferior to us and cost the taxpayers millions of extra dollars every year.”

In addition to his championing police details, Pullman was often the first mouth in line to defend fellow troopers in difficult times. After all, he’d been accused of misdeeds himself. Reacting to proposed reforms that came in the wake of an overtime scandal in 2018, Pullman held a press conference to explain that MSP employees have to steal because there isn’t enough funding for them to have supervisors. “You can’t characterize 99% of this job because of a couple of missteps,” he told reporters. “It’s less than 1% of what’s going on here. … These guys are in one of the most highly scrutinized places on the face of the earth working under unbelievable conditions. They’re all on audio, video. … They’re given directives on an hourly basis.”

By the time of his arrest, Pullman had served more than 30 years on the force. His trooper gig earned him an annual salary of more than $90,000, while his SPAM job paid $71,000. He was also a lobbyist for the State Police—a responsibility worth nearly $50,000 in his final year of advocating for various cop causes on Beacon Hill. Plus whatever he was charging on the union card, milking under the table, or pocketing along the way.

There are several cinematic moments in the complaint against Pullman and Lynch, which details how, among other alleged criminal acts, Pullman had SPAM cut a check to Lynch’s firm, after which she cut herself a $50,000 check from the business, then wrote a personal check for $20,000 to Pullman’s spouse, who deposited it into her and her husband’s joint account at Commerce Bank the following day. According to the complaint, that particular incident happened in 2014, the same year Pullman and Lynch allegedly manipulated deals for MSP to buy several million dollars’ worth of electronic control weapons from the Arizona-based company Taser International. (Six months prior to the criminal complaint being filed against them, my team at the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism identified the suspicious lobbying arrangement.)

There are several cinematic moments in the complaint against Pullman and Lynch, which details how, among other alleged criminal acts, Pullman had SPAM cut a check to Lynch’s firm, after which she cut herself a $50,000 check from the business, then wrote a personal check for $20,000 to Pullman’s spouse, who deposited it into her and her husband’s joint account at Commerce Bank the following day. According to the complaint, that particular incident happened in 2014, the same year Pullman and Lynch allegedly manipulated deals for MSP to buy several million dollars’ worth of electronic control weapons from the Arizona-based company Taser International. (Six months prior to the criminal complaint being filed against them, my team at the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism identified the suspicious lobbying arrangement.)

Around the same time that they were apparently applying pressure to Taser, Pullman gushed about Lynch for a profile of the veteran lobbyist in Boston Business Journal. “She’s unmatched with her work ethic and drive,” he said.

In the article, Lynch described herself as “scrupulously direct and extremely honest,” and promised, “Even when the truth is hard to tell, we will tell it.”

“There is no quit in Anne,’’ Pullman told the BBJ reporter. “I’ve never seen her caught off guard.”

On Aug. 21, 2019, federal agents arrested Lynch, 68, at her home in Hull on charges of fraud and obstruction of justice. Within minutes, halfway across the state, they picked up Pullman in Worcester.

Over decades, the union leader built his reputation in part on exploiting and tirelessly advocating for the God-given right of cops to cash in at every off ramp and intersection under construction.

Ironically, Wilson’s fate may have been sealed by a detail. For him, an off-duty encounter with a city cop was enough to end his career.

It has been a challenge to arrange a clear description of the events that unfolded on Dec. 17, 2000, in Franklin, a city of 30,000 between Rhode Island and Gillette Stadium. A quick rift that transpired between Wilson and Franklin Police Department officers that evening sparked a chain of events that continues today, with the former’s career, reputation, and pension all put in jeopardy. But though it’s central to the story, the play-by-play of the ordeal is also hard to retell, since none of the retrospectives match—including those of Franklin cops, who gave conflicting statements on the record.

The only point of mutual agreement regarding that December day is that the weather was foul. “Cold, kind of misty,” Wilson recalls. His vignettes often come with philosophical or political references—sometimes to noted progressive author Chris Hedges, other times to classic literature. He continues: “It was Dickensian; or really, it was more like Edgar Allan Poe.”

Since the Patriots were winning out of town in Buffalo, Franklin should have been spared the traffic that coagulates on home game days during football season, but three of the four lanes on the West Central Street artery were blocked by a downed power line, making for maddening backups in the 10 o’clock hour.

Wilson says that he was aggravated and confused when he drove his little red Ford Escort in the direction of where Franklin Patrolman Richard Grover was directing traffic. As Grover wrote in a report to FPD Deputy Chief Steven Williams three days after the incident: from “approximately 75 yards” away, “[I] positioned myself facing the vehicle and raised my hands in the air. … waived [sic] my flashlight in the direction of the vehicle, and raised my hand motioning stop. . . . then stopped the flow of traffic from the north travel lane, because I was unaware of the operator in the red vehicles [sic] intentions.”

It’s basically from this point forward that their stories blur. Since Wilson’s side of things was demonstrably discounted during subsequent disciplinary proceedings that stemmed from the exchange (and which are covered extensively herein), I asked him to provide thorough details and hindsight analysis.

To help color his review, in August we meet up in Franklin. Wilson arrives in a late-model Cherokee and parks it in the middle of the lot of a roast beef joint, pointing the hood so that it is facing in the same direction as his red ride was back in December 2000. While the businesses have changed since then, everything else is familiar. It’s a generic thoroughfare—we could be anywhere in the Bay State—but he has a striking sense of where he is.

“I remember it like it was yesterday. This was not a traffic stop,” Wilson emphasizes. “I voluntarily stopped at the traffic control point to ask officer Grover if he wanted me to proceed forward—his hand signals were confusing. This is a key factor from which all legal points emanate. …

“During our brief interaction, Grover was needlessly surly. An argument ensued when he called me an ‘asshole.’ After approximately one minute of heated conversation, during which I repeatedly called Grover ‘unprofessional,’ another officer [Christopher Baker] came forward to make an inquiry. He asked if there was a problem and for an ‘ID.’ Requesting an ‘ID’ was significant because he did not ask for a license and registration, implying that the encounter was transitioning into a traffic stop. My response was, ‘Oh, I have an ID for you.’ …

“While pulling my badge and credential case from my fanny pack—I was holding it—the case slipped from my fingers and fell to the roadway in front of the car. Baker retrieved the badge case and opened it. When Grover saw the MSP ID, he recoiled histrionically, as if he had been struck.”

Grover later claimed that Wilson “did not stop” as requested, and that Wilson “became verbally abusive,” saying the Franklin patrolman “did not know how to do my job, and … was a piece of shit.” Wilson says that he was only trying to ask about the holdup, and that FPD cops grew irritated with his questioning their judgment.

“I asked Baker where he was going with my ID,” Wilson recalls. “He responded, ‘You obviously don’t want it; you threw it on the ground’—even though [Baker] implicitly understood that it slipped from my hands. …

“After approximately seven to 10 minutes had elapsed overall, I moved to the adjacent parking lot of a market. After approximately 20 minutes, I exited my vehicle to inquire about my ID. …

“As I walked toward Baker’s location, I observed a figure walking toward me. … I again asked for my ID, this time directing my request to [Sgt. Koren] Kanadanian. By this time, approximately 20 minutes had elapsed with no response. …

“Baker moved toward me menacingly, closing the distance to less than an arm’s length. A six-footer, he was deliberately trying to be intimidating, looming over me. Feeling threatened, I again asked him for my ID. He then shifted his body and slammed his shoulder into the pocket between my upper shoulder and clavicle. He then said, ‘That’s assault and battery. You assaulted me.’ …

“I recognized this as a worn-out cliché, a police trick, to justify an arrest. I knew what they were trying to do and I wasn’t going to give them what they wanted. I believed at that point that I was going to be arrested and I responded, ‘You hit me and you know it.’ Baker then responded, ‘Yeah, because if you had hit me, I would have kicked your ass. …

“I deliberately lowered my jacket off my shoulders, suspecting an attack was coming. The implication was that I was prepared to fight. I was not going to respond to his taunting and provide a legitimate reason for him to arrest me. …

“As I shifted my glance toward Kanadanian, I perceived him to be panicked as the incident spun out of control. … Kanadanian’s facial expressions toward Baker at this point implied angry disapproval, leading to Baker’s retreat. …

“I pleaded for my ID, directing the query toward Baker. He wound up his arm and hurled the badge case through my open car window, approximately six-feet away. I responded sarcastically: ‘Oh, that’s really professional.’

“Baker replied, mockingly: ‘Have a good night, trooper.’ He accented the [word] trooper to be particularly insulting. All three officers then walked away. I responded by referring to the officers as ‘local pieces of shit.’ Baker’s final reply was a taunting ‘Semper Fi.’ That statement implied that he had seen the USMC tattoo on my upper-left shoulder. I had lowered the sleeves of my jacket to my elbow just low enough that he could observe it in its entirety.”

In Kanadanian’s official account of the run-in, the sergeant later wrote that Wilson “got face-to-face with [Baker] and then shoved him.” As far as details go, those claims were inconsistent with reports made by his colleagues; still, all accounts pegged Wilson as “extremely irrational,” to quote Baker. “At no point in my law enforcement career,” Baker wrapped, “have I ever seen such a hostile display from a fellow law enforcement official.”

Wilson laughs at the suggestion that a cop who he allegedly assaulted responded by simply returning his belongings and sending Wilson on his way without so much as a warning.

“I was the one who was a victim of contact, however slight,” Wilson says. “I didn’t think it was a big deal. I was particularly proud that I handled the insults and threats with restraint. I believed that I proved that state troopers hold themselves to a higher standard.”

Wilson has avoided the small city in southern Mass since 2000. “I wouldn’t even visit my son when he went to college at Dean [College] in Franklin,” he says.

I haven’t pried too much about his personal life, but I can’t believe he’s withheld this detail about avoiding Franklin until now. He continues, “One time I did come here, and it does trigger a negative response.”

“[Grover] called me an asshole.”

Suddenly, it’s a reenactment. Wilson pulls a wallet out of a small satchel that is similar to the belly bag that Franklin cops searched in 2000, and I notice that his leather billfold is holding a badge.

“It’s one of my old ones,” he explains.

“Really, you still carry it?” I ask.

“Hey, man, I’m a Black guy.”

He points to the military-issued lanyard on his neck and the cascade of government-issued IDs in his wallet.

“I gotta be able to save my ass.”

In an unrelated episode with similar overtones, BPD officer Anthony Williams didn’t notice anything out of the ordinary as he exited a sandwich shop on North Main Street in Randolph, about 15 miles outside of Boston through Milton. As Williams returned to his SUV, a Randolph Police Department officer stopped the Black city cop in his tracks. The situation quickly escalated, and before long the suburban uniform was yelling with his gun drawn for head-hunting.

Off duty, out of BPD jurisdiction, and in plain clothes, Williams raised his arms, began slinking toward the ground, and told the guy holding the pistol to his face that he, too, was on the job, and had the firearm and shield to prove it. A member of the BPD for six years at that point, Williams was assigned to patrol Mattapan and Roxbury; but in that moment, south of Boston in the ’burbs, none of those credentials mattered.

As a representative of the Massachusetts Association of Minority Law Enforcement Officers (MAMLEO) told reporters, “When Williams heard the sound of a gun being cocked, he turned to see another Randolph officer aiming a weapon at him” as well. He attempted to explain that he was a cop, but reported being struck in the back of the head and knocked to the ground in response. “While on his stomach, Williams was handcuffed [and] his gun and badge were confiscated.” He was then held for 10 to 15 minutes, according to MAMLEO, “until a Randolph officer who knew Williams confirmed that he was with the Boston police.”

In their own defense, Randolph police said they were looking for an armed Black man driving a white Cadillac Escalade. Williams drove a white Ford Explorer. When MAMLEO asked for an incident report, they were told that since there was no formal complaint or arrest, one was never filed. Nor was anybody held accountable. A familiar denouement.

The Williams stickup, which happened in 2003, is one of several examples of Black cops getting mistaken for perps and harassed or assaulted—seemingly, at least in part because of the color of their skin, which, as Wilson came to understand, was a liability in the MSP, especially compounded with his status as an outsider.

More recently, there’s Jim Jones, a now-former trooper and Bronze Star Army veteran who, like Wilson, earned a master’s degree in criminal justice from Northeastern (in addition to a master’s in public administration from the JFK School at Harvard). As was detailed in a 2017 profile by then-Globe reporter Nestor Ramos, “the indignities piled up” as the Dorchester native trudged through the ranks. His superiors “refused to give Jones a parking space at the troop headquarters where he was third in command, even though everyone else from the janitor on up had a reserved space.” Jones said he was “denied any overtime despite department rules that dictate it be fair and equitable” and “barred from the major and captains’ locker room, leaving him to change his clothes in his office or the hallway.”

Wilson says, and I believe, that his primary objective is to clear his name and obtain his full pension. He’s less interested in exposing larger issues within MSP, which he says is incapable of repenting. He explicitly declines to wholly blame racism for his clash with the department, and says that the main difference between his fallout after Franklin and other rifts like that which Williams experienced in Randolph is that whereas SPAM threw him under the bus, unions typically go to the mat for their constituents. Nevertheless, Wilson seems to seek acknowledgement of the time-honored trend of Black cops being mistreated. He even gave me several printouts of old articles about the topic, including ones about Williams, in a three-ring binder.

Presented in that fashion, they hardly seem like isolated incidents.

The aforementioned critical Commonwealth report about the State Police from 1996 noted, “Only three MSP personnel have been fired since Consolidation, and those only because they were convicted felons. In one of these instances, the individual in question was promoted to sergeant with an indictment pending. … The widespread impression exists in the Department that no action was taken against a trooper found to be harassing a female member, another stalking a former girlfriend, and others driving under the influence of alcohol.”

In this bubble, Black troopers were often the exception. One UMass-Lowell professor who reviewed nearly 300 MSP disciplinary cases testified in US District Court in 1994 that “racial bias played a role and insulated white troopers who would have been discharged.”

On Dec. 29, 2000, 12 days after the Franklin drama, superiors informed Wilson that he was under investigation for the incident as the result of a complaint made by FPD Chief Lawrence Benedetto.

“If I made a written complaint preemptively, then the Franklin Police would be able to construct a congruent counter-narrative.” Wilson explains his thinking at the time. “The MSP would then accuse me of attempting to get ahead of a forthcoming FPD complaint. By refusing to submit a complaint, it compelled the FPD to submit their complaints without a reference. In doing that, they botched the effort. …

“If I made a written complaint preemptively, then the Franklin Police would be able to construct a congruent counter-narrative.” Wilson explains his thinking at the time. “The MSP would then accuse me of attempting to get ahead of a forthcoming FPD complaint. By refusing to submit a complaint, it compelled the FPD to submit their complaints without a reference. In doing that, they botched the effort. …

“I also believed that if I initiated a complaint, MSP command might infer that I was somehow responsible for the incident and I was attempting to get a narrative on the record to get ahead of the story. I sensed innately that I could not trust command, particularly MSP Internal Affairs, to objectively investigate any complaint I made.”

As State Police investigators later demonstrated by allowing conflicting accounts made by FPD complainants to go unchallenged, such a hunch would have been warranted. Documents obtained and reviewed for this article show that their investigation revealed serious discrepancies between different Franklin cop accounts of what happened on that stormy Sunday the prior December; for starters, FPD officers didn’t concur that an assault took place. None of those particulars seemed to matter; the train from Franklin had already left the yard, and was screaming toward the station.

“I was ordered to MSP HQ in Framingham on Jan. 31, 2001,” Wilson says. “Upon arrival I met with my union representative and the union’s retained attorney. I informed them that I was eager to speak to the investigators. I thought the reports were laughably inept and that no competent police investigator would find the conflicting narratives credible. …

“[The union-appointed attorney] quickly made me aware that the charges were serious and that they could ultimately lead to a disciplinary hearing. He also stated that I couldn’t make a statement because IA had already secured confirming statements from the FPD after the reports were submitted. When I explained the multiple flaws in the initial reports, he responded, ‘They don’t care.’

“It is demoralizing that IA at no time looked at the incident from my point of view and the implication that I might be a victim.”

One “obvious fabrication,” Wilson continues, is the allegation that he “started to yell at [Franklin police officers about being] a Marine.” “At the time of the incident,” he explains, “I had been in the Army for approximately 14 years after transferring from the Marines … with the approval of my Marine Corps chain of command. Having been an Army senior noncommissioned officer at that time, I would have never referred to myself as a Marine.”

Even at that early stage of his inquisition, Wilson observed, “The facts were irrelevant. Management sought only to punish employees to make an example of them.”

His recollection of the MSP disciplinary process is consistent with the 1996 report conducted by the state, which analyzed surveys completed by 859 troopers: “The perception of many members may be summarized by the remark of one made in the course of this study: ‘Nothing you can recommend or say in this report you’re doing will result in positive reform of any kind—the absolute only thing that will happen is management will comb through it trying to figure out who said what so they can mete out their usual vindictive, vicious, and arbitrary punishments; there is no interest whatsoever in progress or competence, and wherever the management can lash out and make people pay for telling the truth, believe me they will—as they have in the past, many times, without hesitation and without logic.’”

“The Massachusetts State Police understood that their employee was the victim of abuse at the hands of another police agency,” Wilson says about his own tribulation, “and they took extraordinary means to cover it up.”

“The union benefitted any time a sworn employee was subjected to this harsh process, because it compelled troopers to maintain a union affiliation—with associated dues—at a time when such an affiliation was voluntary. Women and minority troopers were particularly skeptical of the union because it was perceived to be hostile to their interests. Minority troopers were in the process of starting a rival association to meet the needs of its members and the union was wary, and fearful, of the alternate political power.”

Wilson notes that while he was not part of that organizing effort, he did “support their efforts to secure more equitable treatment of all troopers.”

In July 2001, Wilson phoned his union-appointed attorney’s office for a status update. The partner who was taking over his case “warned that he had secured the transcripts of the IA interviews with the FPD [conducted after the initial reports were made] and that they were damning.”

Upon closer inspection of the transcripts, Wilson “immediately noted that the IA questions were vague and leading and there was no attempt to resolve obvious conflicts,” but says his lawyer pushed for “a quick settlement.”

“Officers … were being prompted to implicate me in acts of misconduct even as the officers attempted to walk back their initial accusations,” Wilson says and documents confirm. He gives the example of how “Baker, who initially embellished the fact that my badge slipped from my fingers by absurdly adding that it struck him in the chest, now reported that it was accidental.”

The whole time, Wilson says, “I was eager to give my account.” The chance never came; the department proceeded with particulars for formal charges based on the reports and interviews IA had from the FPD accusers.

In August, MSP’s Internal Affairs (IA) unit formally charged Wilson with various counts: using “inappropriate and profane language” in his interaction with Franklin police; “present[ing] his official badge and identification to officers of the Franklin Police Department for other than official business”; and, most damningly, “fail[ing] to maintain a level of personal conduct in keeping with the highest level of law enforcement by engaging in an altercation which resulted in physical contact.” (Wilson notes: “While FPD [officers] alleged that I assaulted one of their officers, they did not submit a report from the alleged victim to the MSP with the two initial reports,” one of which made no mention at all of breached physical boundaries.)

The 9/11 attacks on the US slowed down many bureaucracies, but not before IA advanced its impugnment of Wilson toward a foregone conclusion. By the fall, Wilson was facing a formal prospective punishment of a six-month suspension and a reassignment to Western Mass.

“The transfer was particularly daunting because it meant a daily commute of over 100 miles to work, ensuring overwhelming inconvenience and exhaustion,” Wilson says. “I recognized this as a form of intimidation to compel me to accept a negotiated settlement.”

In meeting Wilson that October, his SPAM-appointed attorneys explained the significant risk of proceeding with an MSP trial board. Wilson was determined to clear his name though, insisting as he still does today that he had nothing to hide, and pointing to corruption in the Franklin police ranks. Two years earlier, the Globe Spotlight Team exposed a ring of sketchy city officials including a police chief who moonlighted as a real estate developer. Wilson, who had turned sleuth in researching all tangents connecting to his case, ordered his lawyers to sue the FPD. They refused.

“In retrospect, I understand that the MSP misconduct investigation and disciplinary process was not about determining fact but using a formulaic process for inferring guilt while simultaneously ignoring any repudiating facts, information, or circumstances,” Wilson says. “The process did not feature a logical investigative process but purposely sought to keep my account off the record. The typical uniformed employee, facing this draconian and seemingly inevitable punishment, would settle for a lesser punishment negotiated by the union’s legal counsel.”

Not Wilson. He recognized the whole “procedure as similar to the defense the poor must endure from disinterested public defenders who generally do not vigorously defend their indigent clients, even if they are innocent.”

“My attorneys were dismissive of my claims and the evidence I gathered and eager for me to admit guilt.”

As the partner who handled his case later wrote in a legal dispute with Wilson over the quality of his firm’s work, in an exchange at his law office, “Trooper Wilson exhibited confrontational emotional and irrational behavior. In fact, his actions were very similar to the type of overly aggressive and confrontational conduct alleged against him.”

Wilson denies that account, saying that the attorney exaggerated the conversation in legal correspondence.

Adding to his distrust of those in his midst, a few months later, Wilson learned that attorneys from his union-appointed firm also acted as labor and employment counsel to the Franklin Police Association. The discovery that he was being flanked by the same team which, in unrelated cases, represented officers from the department behind the allegations against him was unnerving. Wilson started seriously believing that MSP leadership, or at least SPAM, was out to ruin his career from the inside.

With less than three months to go before Wilson’s hearing, the firm that had been representing him passed the case to another lawyer with experience backing cops in comparable circumstances. Wilson explains, “I received a letter [in December 2001] … informing me that responsibility for my representation was forwarded to an alternative firm. This move was made without my prior consent.”

Wilson took his chances, even though he “understood that this was risky since the trial board’s verdict was highly subjective and easily subject to command manipulation.” Along with the charges, the department’s Division of Standards & Training offered the choice of facing an internal trial board or accepting the recommended disciplinary actions: “Six Months Suspension Without Pay”; “Transfer from Current Duty Assignment”; “Appropriate Training as Determined by the Superintendent.”

“By refusing to settle,” he explains, “I suspected that the board would determine guilt irrespective of fact and would have to risk that any guilty verdict could be overturned on court appeal. I could not admit guilt on any charge, no matter how minor, because it became a permanent record that could be used against me in any subsequent disciplinary action.”

The MSP trial board is not your typical court apparatus—one external review of the department found it to lack anything resembling a legitimate disciplinary system—and Wilson was no ordinary defendant. He instructed his lawyer to throw shade on the Franklin Police Department, and to highlight the variances between statements—some reports, for example, were inexplicably filed weeks after the incident. “The cross examination must be unrelenting and questionable responses must be met with comments that challenge [the] credibility” of Wilson’s accusers, he wrote in a note to his attorneys at the time.

The trial board convened in Wilson’s name at MSP headquarters in Framingham, not far from the bridge where he had become inspired to join law enforcement in the first place. Deliberators met on Feb. 15, 2002, and for a second time on March 19. Wilson suspected all along that he was going to be “submarined”; less than a week before the hearing, he learned that the board members he favored—and who he perceived could at the very least evaluate him fairly—were replaced with new wild cards. According to Wilson, the race of his jurors, like that of the internal affairs investigators making trouble for him, didn’t matter.

“Significantly, every action involved with my investigation included one Black command representative,” he says.

As he tells it, the deck was stacked.

As he tells it, the deck was stacked.

“My attorney’s performance was so incompetent that I stopped the proceeding for an off-the-record discussion,” Wilson recalls. Other testimonies raised numerous red flags that could seemingly exonerate him, one of the most striking being that stories of the Franklin cops involved changed dramatically by the time they told them at MSP headquarters. Remarkably, officer Baker said that he had been ordered to not write a report, while his sergeant disagreed with the claim.

“[My attorney] ended the examination of [an IA representative] without addressing the conflict,” Wilson says and transcripts confirm. “No MSP IA investigator ever asked the most glaring question: Why didn’t you give him a citation or arrest him? [My attorney] asked no probing questions, implying he would recall [the IA representative] to re-cross examination later in the proceedings.”

Wilson “demanded” that his lawyer “compel all three IA investigators and the FPD command, the chief complainants, to testify.” “He refused,” Wilson says. “He made a half-hearted reference to the news reports [about corrupt Franklin cops] I had compiled for entry to the record, but the board refused to consider the reports, claiming that referencing them was an attempt to ‘embarrass the witnesses.’” (At one point, Wilson’s attorney was told to “proceed with another line of questioning.”)

“My claim as a whistleblower was that the entire investigation and subsequent charges constituted a malicious prosecution,” Wilson says. “Though he was a zealous advocate in a few instances, my lawyer failed to construct a cogent defense and more importantly, never went on the offensive.”

Inconsistencies and revelations from the testimonies of FPD officers that could have proven Wilson’s innocence were ignored. Rather than impeaching their accounts, toward the end of the proceedings, one MSP prosecutor used his closing statement to commend the Franklin officers for their participation. Wilson, however, “was told that allowing me to make a final statement was inappropriate.”

On April 4, the trial board stipulated a guilty finding, and the following month ordered a four-month suspension without pay commencing immediately. The punitive ruling implied a spotty work history: a suspension in ’92 for “insubordination and disrespect to an officer”; “a letter of counseling for a verbal confrontation with a citizen” in ’96, as well as two more letters in ’98 for “verbal abuse, one of which was for a confrontation with a State Police dispatcher.” “Trooper Wilson clearly has a long history of verbally abusing people who invoke his ire,” the board wrote.

Wilson says that all of the infractions listed in the guilty finding are not only nonsense, but demonstrate the ongoing vindictive treatment he faced. Compared to criminal acts committed by white troopers who kept their jobs, the charges they suspended him for are laughable. In his time on the force, others had received suspensions for selling guns and cocaine, beating perps in custody, and sexually assaulting women during traffic stops. Wilson, meanwhile, was himself the victim of harassment.

“If he was walking around acting pissed off,” a retired white trooper who asked to be quoted anonymously surmised, “it was probably because [Wilson’s] a smart kid, and he would have realized that as a Black guy coming from the Mets, he was never going to be teacher’s pet.”

“The board cited a dubious suspension I received in ’92,” Wilson says. Back then, he explains, Wilson was still a Met, and argues that “alleged misconduct committed in one’s prior agency could not be cited when deliberating any Massachusetts Department of State Police disciplinary action.” He also says the past punishments cited are “fabrications.”

“I received no letter of counseling for a verbal abuse of any citizen, and the incident with the dispatcher cited by the board never advanced beyond the primary investigation stage,” he says. “I have no sustained complaint of verbal abuse of any citizen and only four complaints overall in over 15 years of service. Allegations that I have a long history of verbally abusing people are not only false, but the board deliberately misconstrued the facts to put me in an unfavorable light so as to justify their finding and recommendation of a 180-day suspension without pay.”

As for specific findings about what went down in Franklin 14 months earlier, Wilson has spent 20 years connecting dots and documents, and building a case that challenges various aspects of the Kafkaesque kangaroo court which censured him.

“The board cited as their justification for guilt that I had thrown my ID at Baker and it struck him,” Wilson says. “Although the badge case never struck Baker and it was a foolish embellishment, he subsequently admitted that the badge case slipped from my fingers, thereby removing that aspect of the allegations from further conversations for disciplinary sanction.”

He continues: “Paradoxically, the board found me not guilty of potentially the most serious allegation—that I attempted to use my MSP ID for personal gain or to avoid illegal acts. With this verdict, they acknowledged that I committed no violations or precipitating acts, and that all subsequent actions undertaken by the Franklin Police were improper.”

The ruling even stated, inconceivably, that the trial board “credits the testimony of the Franklin Police Officers because they had nothing to gain by fabricating the incident and that they appeared to be reluctant to take any action against a state police officer both at the time of the incident and by testifying.”

Though the trial board reached its guilty finding in April 2002, Wilson says he “was not provided any legal documentation or asked to sign any acknowledging documents” at that time.

“I was not informed of the findings until May 3, when a general order was disseminated throughout the department,” he recalls and documents show. “I was ordered to return all issued department gear and to commence the ordered four-month suspension.”

In August 2002, while on suspension, Wilson brought his case to the Mass Department of Labor and Workforce Development in an attempt to get his unemployment insurance reinstated. The reviewers agreed with his argument, and gave him back full benefits: “The ruling in my favor was handed down after I returned to duty, so I received approximately $9,000 in unemployment benefits after returning to work. I estimated that I lost over $25,000 during the suspension. In addition, I was forced to pay over $1,000 a month to maintain my health insurance that covered my son.”

At a crossroads, in September 2002 Wilson returned to full MSP duty, but the relationship was on the rocks. He made “it clear to command elements that I intended to take any action necessary to bring the case into court,” and in return, the department hardly threw a homecoming party. Among the potential motives for pushing Wilson out, he says that he was advocating for a woman trooper who was getting harassed by a supervisor. Plus, as he explains, he was not “the kind of Black guy the State Police like.”

“For all their grandstanding about my so-called anger issues,” he notes, “the anger management mandated in the findings was never ordered or even mentioned. By the time I had returned to work, management knew that I was aware of the withheld findings and the legal conflict of interest and they hoped I would not take any further action. They didn’t want me telling my story.”

Back on the job, Wilson kept thinking about what transpired. As far as he was concerned, his department screwed him. Worsening matters, he argues that by neglecting to share the trial board findings with him in a timely manner, his attorney and the MSP dashed his chance of finding justice through the appeals process, since the deadline to formally seek one had expired.

“The denial of a final statement is an additional point of contention that would have constituted a district court appeal,” Wilson says. All these years later, he still harps on the injustice of his not getting a chance to contest the decision, arguing that the “deliberate withholding of the findings and recommendations document … suggests a cover-up” by MSP commanding officers.

“My attorney should have understood instinctively that there were grounds for appeal on several points. The appeal could have been requested based on procedural errors. For instance, the trial board misrepresented my disciplinary record in support of their finding.”

In late 2002, Wilson initiated a malpractice suit against his first union-appointed attorney. The following January, he voluntarily left the MSP to go on active duty as a reservist at Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri. While on base there and during a subsequent assignment that lasted for most of 2004 at Fort Benning in Georgia, he researched and filed a complaint against the Franklin Police Department alleging defamation, among other accusations.

In an attempt to seek redress in 2008, while still on active Army duty in Missouri, Wilson petitioned the Massachusetts Civil Service Commission to consider his case. “I based my prospective complaint on a newly discovered understanding of administrative law from working toward a master’s degree in public administration, the conditions being that a defendant in a case such as mine must be issued a written justification for punitive action,” he says. “My argument was that the State Police deliberately withheld my finding.”

Wilson recalls being “pleasantly surprised” when the Civil Service Commission granted him a hearing.

“I flew to Boston from Missouri and appeared in full Army dress uniform before a hearing officer and a State Police legal representative.”

But from the outset, Wilson says, “it was apparent that the proceedings would be adversarial.”

He wanted closure. Instead, Wilson waded deeper into legal and professional lava that still burns today.

“The hearing officer implied that I had no legal standing to have my case heard, totally downplayed the impropriety of the MSP withholding the finding, and refused to even listen to my argument,” he says.

“I asked why the commission compelled me to fly from Missouri to inform me that I had no legal claim to such a hearing. He gave no answer other than Thank you for your service platitudes.”

Toward the end of his reign, Pullman was pulling in more than $200,000 annually, according to state records. It appears those earnings and anything he sneaked in the back door have run out. Though seven SPAM board members voted to pay Pullman’s legal fees after he was indicted, the union ultimately stopped supporting their guy about one month into preliminary court proceedings. Things worsened for him in November 2019, when his marquee attorney Martin Weinberg, noted defender of dead billionaire and celebrity child rape maestro Jeffrey Epstein, withdrew from the case.

Pullman’s trial, a circus advertising more than 50 witnesses, is set to commence next month. Leading up to the big show, Pullman has been home on $25,000 unsecured bail, and is apparently in touch with some former associates. In late 2019, his court-appointed lawyer successfully argued for his client to be able to speak with two MSP pals, provided they don’t talk about the case.

In the wake of the Pullman scandal and other transgressions, State Police and government leaders have done what they always do to deflect unflattering press—announce token hirings, stall and settle hideous discrimination claims, and posture, each instance an intermission in a performance that has spanned generations. The costumes may change, consolidations and mergers occur, but the plot and script remain. Even as protests over law enforcement abuses erupt from coast to coast, Massachusetts politicians have failed to rein in their trooper cronies, while only time will reveal how tepid new statewide changes to policing will play out on the street.

Whatever happens moving forward, condemnations of the force will probably remain rare and are not recommended for those running for office. One of the last pols to publicly blast the MSP was Democrat Jay Gonzalez, who attempted to unseat Gov. Charlie Baker in 2018.

“When is he going to take responsibility for what’s happening on his watch?” In his losing gubernatorial bid, Gonzalez unsuccessfully tried to make law enforcement reform—and MSP in particular—a central issue. “Every single one of these indictments and guilty pleas was for criminal conduct during the Baker administration.”

During that race, in April 2018, MSP brass announced changes, including tracking devices to make it harder for troopers to cheat on their timesheets. And in September 2019, with Pullman gone from SPAM, his replacement, Trooper Corey J. Mackey, pledged in a press release, “I believe that we must do better as an Association, and I intend to start reforms immediately.”

Still, it’s hard to spot any tangible progress. Proposed attempts by lawmakers to check spending and bad actors have not developed in any meaningful way, while in November 2019, with Pullman in the spotlight, Col. Kerry Gilpin, a 25-year veteran of the department who was put in charge to clean house, retired after only two years in the top position.

In Franklin, officer Williams, the deputy who routed the reports between his department and the State Police IA unit investigating the incident that altered the trajectory of Wilson’s life, was promoted to chief four years later.

Eight years after that, he retired in good standing. At a blowout sendoff, Benedetto, the former chief who was in charge of FPD when a Black statie ran afoul of his cops on a windy night in December 2000, spoke to a local reporter.

“I wouldn’t miss this,” said Benedetto, who flew up from his home in Florida for the occasion. “I worked with these guys for 30 years, they’re really good people.”

It took more than three years of searching, but in April 2004 Wilson finally secured a litigator willing to bring his suit against the Franklin Police Department. Just a few months after paying a $10,000 retainer, though, his lawyer stopped returning calls, and eventually wrote to Wilson that his case was forwarded to a colleague.

“I understood from past experiences that [the replacement attorney] was affiliated with elements of the prospective defense in my case, including the commanding officer of the MSP Internal Affairs section.” As Wilson saw it, he’d been double crossed by his own lawyer—for a second time. “This was a significant conflict of interest. There was no way I would have consented to the appointment if given prior notice. There was no significant movement in the case thereafter.”

His next attorney burned through a $14,000 retainer and accomplished nothing, while a lawyer Wilson hired after that was found by the Massachusetts Board of Bar Overseers (BBO) to have misappropriated clients’ funds while representing Wilson. (His luck with lawyers was lamentable; the advocate he hired in April 2004 had his license suspended by the BBO for infractions committed while he was retained by Wilson to sue the FPD.)

Professionally, Wilson excelled throughout the mid aughts, earning advanced degrees in security management and public administration, and commendation medals in the service. Upon his release from active duty in 2008, Wilson says he “felt regret that I had not made a career of the Army.”

“I thoroughly enjoyed my stint,” he says. “I was struck by the Army’s professionalism and the senior leadership’s commitment to the care and development of their subordinates. The Army encouraged professional development and superior performance, where the State Police seemingly sought ways to belittle and degrade selected employees. After a wondrous Army experience, I dreaded returning to that toxic environment.”

He was about to enter “a particularly stressful period because I understood that, for the first time, I would be directly confronting State Police officials, informing them that I was aware of the vast conspiracy behind my prosecution.”

Back with the MSP, a department psychologist temporarily placed Wilson on unfit for duty status so that he could seek counseling. “I complied with this directive,” Wilson says. After nearly six years of active military duty, Wilson had accrued enough comp, sick, vacation, and personal time to return to paid MSP status without returning to duty. “Additionally, [the psychologist] stated I should limit my contact with anything pertaining to the State Police.”

Sooner than he wanted or anticipated, in early 2009, Wilson “was informed that I would be required to go on limited duty,” which “implied administrative tasks, not carrying a weapon, nor interacting with the public.” “The order was mean-spirited,” he says.

“The response I received was mixed,” Wilson adds. Despite attempts to reinstate him, he would never actually return to the job or wear the uniform again. He recalls: “Civilian administrators were welcoming, but my troop commander was confrontational. He informed me that I would be required to complete mandatory training and that I was expected to immediately return to duty. He also implied that I was somehow derelict in my duty to the State Police by remaining on active duty [in the Army] for such an extended period.

“To infer that my primary responsibility was to the MSP was ridiculous.”

Despite having some misgivings about orders to appear in front of a status hearing board with the same kind of SPAM representation that failed him before, Wilson went through the process, which he says felt excessively punitive. He was also made to undergo a physical evaluation, as well as a psychological one, and says he welcomed both. “I anxiously sought out the psychological exam so that I could inform the examiner of my circumstances with the agency prior to active duty, as I believed the incident had a lasting, negative effect on my psyche and it needed to be documented.”

“Trooper Wilson is suffering from PTSD,” the resulting report noted. The MSP occupational health director continued, “interestingly, not because of military service, which he states has been a wonderful experience, but because of the events starting with the incident of 12/17/00 and continuing through his unpaid suspension in 09/02.”

“He trusts no one in the MSP, feels wrongly treated and isolated from every faction of the department.”

Wilson says the results of that psych exam were subsequently used against him. Meanwhile, the reluctance of superior officers to cooperate with his Army assignments became an immediate concern. “I viewed their refusal to allow me to leave the state for military duty as petulant.”

Three months later, the same state-commissioned psychiatrist re-evaluated Wilson, this time finding, “His mood was entirely normal … In contrast to our meetings in May 2009, Trooper Wilson exhibited far less emotional reactivity when discussing the disciplinary actions against him; he exhibited a more objective view of the incident. … Wilson acknowledged continuing concerns regarding his sense of being treated unfairly, but did not exhibit preoccupation or a fixed in transient emotional posture regarding this issue.”

Though that August assessment found “no psychiatric contraindication to Trooper Wilson resuming his previous duties as a state trooper with no restrictions,” that was not his fate. Around the same time, he was given a general discharge, “deprived of the opportunity to serve approximately 30 more months in order to secure a 75% pension” (his current take is 62% of his highest pay totals, which Wilson says pales in comparison to the damages the department has caused him and his family).

In the August report, the shrink analyzed: “I explored with Trooper Wilson his feelings regarding the litigation over the years and his sense of being treated unfairly. He acknowledged that his PTSD symptoms were heavily stimulated by preoccupation with ongoing litigation and his sense of being a victim of Injustice. He asserted that his sleepless nights and flashbacks were largely based on ‘worrying about where it was going to go’ (referring to the litigation).

“Trooper Wilson expressed his feeling that if the state police would ‘clean up my record, a burden would be lifted.’

“He described his conviction that the trial board’s findings and recommendations had been withheld from him to his detriment. Yet he was able to state, ‘It has been 10 years; it is time to put it behind me.’”

That was more than 11 years ago.

Last December, on the week which marked two decades since he drove through Franklin on a sullen Sunday evening, Wilson was still contemplating his quagmire.

“It isn’t strictly racial,” he says. “It’s more about those on the ins and those on the outs. I was on the outs and, more importantly, I had cultivated nobody in senior leadership to go to bat for me at the outset of the incident.

“This shouldn’t be viewed as a case of racial discrimination. There were Blacks involved at every level of the incident. It was clear that they were instrumental in the coverup attempt because they knew this would give the agency a black eye. I don’t even blame them for trying to cover it up—they are certainly not going to admit fault and open themselves to a lawsuit and public scorn.

“But when I say they didn’t like me, and I’m sure some didn’t, that’s expected in an agency comprised mostly of alpha males. What is more probable is that they didn’t know me, and nobody has a problem making an example of someone they don’t know.

“I also suspect I was perceived as being too smart-assed for my own good. In that way, I have to accept some blame for being tone deaf to the way large agencies like the MSP really operate.”

The connotations of a PTSD diagnosis, even one that was debunked after further examination, cannot be understated. Any indication of a mental disorder, particularly for a service member, is almost immediately disqualifying.

Whatever condition I did suffer from resulted from my fear of retribution as a whistleblower. After all, there had been flagrant attempts to intimidate me and my family. In 2003, while away on active Army duty in Missouri, I made a formal complaint to my station commander that an internal affairs investigator was following my son and his mother as they shopped for the holidays.

My initial diagnosis in May 2009 stipulated that I refrain from association with anything related to the MSP, as it might trigger a PTSD response. I had enough accrued time that I could have followed those recommendations, and remained on the payroll while I sought counseling, but my superiors attempted to force me back to duty despite the diagnosis of the psychologist.

I was wary that the State Police would try to contrive an incident to place me in a negative light and undermine my credibility. The command element was extremely hostile, and in response I publicly stated that it was probable I would return to active military duty, an option that was more attractive.

As I was being paid out of accrued sick time, I was required to prove I was undergoing treatment. Although I no longer felt particularly traumatized, the sessions were extremely therapeutic. We discussed the incident, my status with the State Police, and my emotional response, but mostly our conversations were about current events, sports, and the military. We also talked about my future as a police officer and a soldier. I explained that I was not certain that I could return in the long term if I continued to feel threatened.

After approximately four months, I was considering returning to duty, but the State Police were hostile, seemingly resentful that I could collect pay almost indefinitely without returning to duty. Command seemed determined to bring me back into State Police environs.

In early 2009, I was seeking a permanent Army unit to join, and informed my State Police command that I would be traveling to Maryland for weekend Army Reserve training. My request was denied, as I was theoretically on sick leave. I countered that my status was unique because my condition did not prevent Army duty, and contacted a Veteran’s Affairs administrator to report a formal complaint. This incident made it evident to me that the State Police would not cooperate with me going forward.

Around June, I was informed by my local Army unit, one attached to FEMA based in Maynard, Mass, that I would be put on active-duty orders for approximately four months, paid full-day status to support daily operations. I was on temporary active military duty and not drawing a paycheck from the Commonwealth, and I forwarded the orders to MSP headquarters through my station commander.

In July, the State Police ordered me to meet with a psychologist to determine my fitness for duty. I complied with the request, even though I was on active military duty status at that time. During my meeting with the psychologist, I provided an extensive case history, explained particulars, and reaffirmed that I did not accept the PTSD diagnosis. I informed him that I was fearful of retaliation, as I contemplated legal action and reported that the MSP’s response toward me was hostile.