“The thing that you represent face to face with me has no heart in its breast.”– Marx

“There is no life in this body.” – Dracula

In Dictionnaire philosophique, which he first published in 1764, Voltaire has an entry titled “Vampires.” It begins with this paragraph:

What! is it in our eighteenth century that vampires exist? Is it after the reigns of Locke, Shaftesbury, Trenchard, and Collins? Is it under those of d’Alembert, Diderot, St. Lambert, and Duclos that we believe in vampires, and that the reverend father Dom Calmet, Benedictine priest of the congregation of St. Vannes, and St. Hidulphe, abbe of Senon—an abbey of a hundred thousand livres a year, in the neighborhood of two other abbeys of the same revenue—has printed and reprinted the history of the vampires, with the approbation of the Sorbonne, signed Marcilli?1

The vampires Voltaire refers to took hold of the Western imagination in the fourth decade of the eighteenth century. Of course, legends of creatures resembling people who live by sucking the blood of human beings predate the 1700s. Voltaire recognizes this fact further on in his entry, although he underestimates the longevity of the legends, tracing them back only as far as a Christianized Greek antiquity. As of today, the earliest written reference to vampires that has come to light occurs in cuneiform tablets from ancient Assyria. Apart from this written evidence, there is no way of being certain when belief in the existence of vampires originated. Montague Summers is undoubtedly correct when he writes in his book of 1928, Vampires, Their Kith and Kin: “The legend is worldwide and of dateless antiquity.”2 But the fourth decade of the eighteenth century witnessed the occurrence of a phenomenon that has since become familiar – the vampire craze in modern society. In this, its initial appearance, the craze was occasioned by reports on events in Serbia and Wallachia by military and medical officials of the Austrian empire, which had recently annexed these territories. Two of the reports, which were especially detailed and lurid, concerned the exhumation, staking, decapitation, and burning of the supposed Serbian vampires, Petar Blagojevich and Arnold Paole, as well as their numerous victims (who in reality appear to have succumbed to epidemic disease). The Austrian officials reported that, upon exhumation, the corpses of the vampires were seen to be ruddy in appearance, oozing fresh blood from their orifices, with their hair and finger nails continuing to grow (all, in fact, perfectly normal stages of decomposition). The reports made their way into the newspapers of Western Europe where they caused quite a stir, even among educated readers. The question Voltaire poses in the first paragraph of his Dictionnaire entry is: Why does the superstition of the vampire flourish in an age of Enlightenment? How is it compatible with a time when reason and science are on the ascendant? He does not answer this question directly, but instead goes on to write, in the second paragraph of his entry:

These vampires were corpses, who went out of their graves at night to suck the blood of the living, either at their throats or stomachs, after which they returned to their cemeteries. The persons so sucked waned, grew pale, and fell into consumption; while the sucking corpses grew fat, got rosy, and enjoyed an excellent appetite. It was in Poland, Hungary, Silesia, Moravia, Austria, and Lorraine, that the dead made this good cheer. We never heard a word of vampires in London, nor even at Paris. I confess that in both these cities there were stock-jobbers, brokers, and men of business, who sucked the blood of the people in broad daylight; but they were not dead, though corrupted. These true suckers lived not in cemeteries, but in very agreeable palaces.3

Since belief in vampires is an irrational superstition, Voltaire is not surprised to find it in Poland, Hungary, Silesia, Moravia, Austria, and Lorraine, in other words, in the more remote parts of Europe that were still under the unquestioning sway of medieval religions. The real mystery is that the belief should have caught on in London and Paris, the two capitals of the Enlightenment. And yet, in those cities, true suckers dwell who come close to embodying the irrational myth. Although they are not literally dead, these parasitic monsters are morally corrupt. And while they do not prey on the living under cover of darkness, they suck their blood in broad daylight. The real vampires are the bourgeoisie. It is surprising that Voltaire should name them so directly – the stock- jobbers, brokers, and men of business – since the Enlightenment that he exemplifies is supposed to have been busy sweeping away the culture of aristocrats and absolute kings. But here Voltaire is directing his barbs, not at the old feudal order, but at the rising capitalist one.

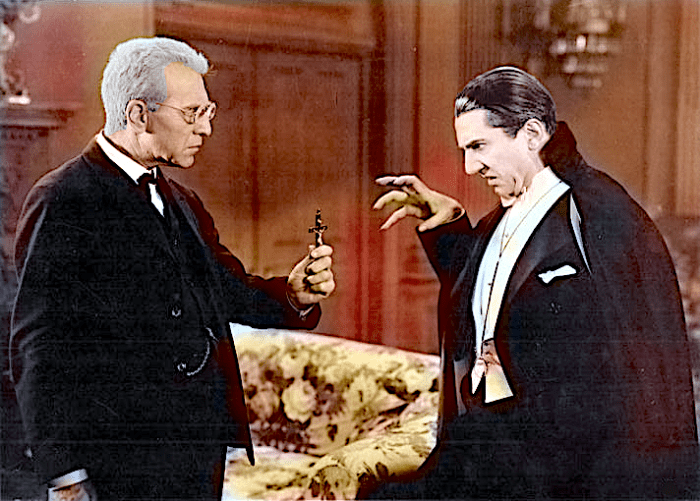

Nearly one hundred and fifty years separate Voltaire’s observations on vampires from Bram Stoker’s novel, Dracula (1897), masterpiece of the genre of vampire literature, and source of the eponymous character who has since become the most frequently recurring figure in film history. Unlike Voltaire’s “true suckers,” however, Count Dracula is neither a stock-jobber, a broker, or a businessman, but a member of the highest order of the boyar nobility at the borders of Serbia and Wallachia, where the historical Dracula – Vlad the Impaler – repelled the advances of the Ottoman Turks in the fifteenth century. The nostalgia of the literary Dracula for the blood shed on the battlefields of the border regions, and his outright expression of contempt for the peasants of his native land, underscore the fact that we are dealing here, in the late nineteenth century, with an anachronistic survival of the ancien régime. In this case the living dead is the remnant of a feudal society that refuses to give up the ghost.

In the same century, about fifty years before Stoker published his novel, Karl Marx and Fredrick Engels continued to develop the trope that Voltaire had pioneered. Consider the following passage from The Condition of the Working Class in England, written by the young Engels in 1845:

It may be added that the lack of religious belief among the proletariat is most clearly seen in the Socialist doctrines. This is all the more significant when we consider that although English workers reject religion in practice without much conscious thought, they nevertheless recoil from an open admission of their lack of faith. One more it may be expected that hard necessity will force the workers to give up their religious beliefs. They will come more and more to realize that these beliefs serve only to weaken the proletariat and to keep them obedient and faithful to the capitalist vampires.4

This passage is almost a paraphrase of Voltaire’s entry in the Dictionnaire philosophique, including its reference to the persistence of vampires in the capitalist class during a period of enlightened disenchantment with religion.

In 1852, Marx continued to build upon this trope in his Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte:

The bourgeois order, which at the beginning of the century set the state to stand guard over the newly emerged small holdings and fertilized them with laurels, has become a vampire that sucks the blood from their hearts and brains and casts them into the alchemist’s caldron of capital.5

This time the victim of the vampiric bourgeoisie is not the class of wage-workers, as it is in Engels’ book, but that of small property-holders, mobilized by Voltaire’s “stock- jobbers, brokers, and men of business” to support them in their battle against the feudal order in France, and then sent bloodless to the caldron or the grave by the true suckers of big capital.

It was not until the Grundrisse of 1857 – his preliminary studies for Capital – that Marx was able to move beyond the Voltairean trope and turn the idea of the vampire to good theoretical account. To do so, he had to detach the vampire-image from both the bourgeoisie as a class and its specific class-fractions in the business world, and attach it to the concept of capital as an impersonal force. The relevant passage is:

Capital posits the permanence of value (to a certain degree) by incarnating itself in fleeting commodities and taking on their form, but at the same time changing them just as constantly; alternates between its eternal form in money and its passing form in commodities; permanence is posited as the only thing it can be, a passing passage — process — life. But capital obtains this ability only by constantly sucking in living labor as its soul, vampire-like.6

The basic concept is dialectical. There is an identity of identity and difference – as Hegel might say – between fixed and circulating capital. Capital must constantly renew its value by converting itself into an impermanent stream of commodities that exchange on the market for money (capital in its abstract, “eternal” form), and then converting part of that money into the commodities necessary to replenish fixed capital (buildings, machinery, etc.). Thus the permanence of capital can only be understood as the permanence of flux, the permanence of passage and process, the permanence of what Marx calls “life.” But here is the thing. Capital is dead, whether in the form of salable products or buildings and machines. By itself, it does nothing but lie there, passive and inert. It gets whatever life it has from the labor that creates it, vivifies and revivifies it, and makes it move throughout the whole of its fluctuating circuit. Even more than this, however, capital acquires from labor its ability to augment itself, its restless capacity for growth. For the commodities labor produces are converted into money that equals more than the sum of the labor costs involved in the production process plus the cost of replacing used-up capital. It also contains a surplus, which is the money-expression of the unpaid labor the worker expends during the working day. When this surplus value is reinvested, the result is not just renewal of the original capital, but the accumulation of additional capital. Each time capital moves through its circuit, it grows, or at least does so short of economic crises or miscalculations about consumer demand. The demonic, diabolical, vampiric dimension of capital is its limitless thirst for surplus-value in the service of accumulation as an end in itself.

It can hardly be coincidental that, when Marx published the first volume of his masterwork, Capital ten years after writing the Grundrisse, the chapter in which he refers to the vampiric nature of capital – no less than three times – includes a comparison of the capitalist class with that of the Wallachian boyars. Marx did not live to read Stoker’s novel, whose central character, Dracula, is precisely such a boyar, but he must have been aware of the fact that Serbia and Wallachia were the primary regions from whence the vampire myth made its way to Western Europe in modern times.

The chapter concerned is titled “The Working Day.” The question Marx asks is, how is the length of the working day determined in a capitalist society? We must begin by recognizing that there are upper and lower limits. The upper limit is the length of time spent at work that depletes the worker’s physical and mental capacity to labor. The lower limit is the time required to produce the value-equivalent in commodities of the worker’s wage. Beyond the upper limit, the worker is no longer capable of working, and below the lower limit, the worker no longer makes a profit for the capitalist. What is at stake here is the ratio between necessary labor time and surplus labor time. During necessary labor time, the worker produces the commodities that, when sold, pay for his or her wage. During surplus working time, the worker creates commodities the value of which exceeds the wage. It is this value created during surplus labor time that is the basis of the capitalist’s profit. Now Marx tells his readers that capitalism did not invent surplus labor time. It exists in every society in which a dominant class lives off of the material surplus created by the direct producers, which is to say that it exists in all class societies. In class societies prior to capitalism, the extraction of a surplus is limited by a static purpose, that of maintaining the traditional level of consumption of the dominant classes. But in capitalism, such extraction has no limit since its purpose is to feed the process of capital accumulation as an end in itself. It is only under the latter circumstances that the thirst for a surplus – and therefore surplus labor time – becomes insatiable.

The division of the working day into necessary and surplus labor time is not obvious under capitalism. According to the labor contract, the worker is the owner of his or her labor time, which the capitalist purchases in its entire duration in exchange for a wage. For this reason, in the working day as a whole, necessary and surplus labor time are indistinguishably combined. Let us assume that the working day in a capitalist factory is 12 hours and that the worker makes the equivalent of her wages in 6 of them, so that she produces a surplus in the remaining 6 hours of the day. Since the ratio of necessary labor time to the working day is 6/12 = 1/2, and the same ratio holds for surplus labor time, we could just as easily say that the first half of each hour of the working day is necessary labor time and the second half surplus labor time. We could say the same thing about each minute or each second as well.

In order to illustrate the effect that the insatiable thirst for a surplus has on the relation between necessary and surplus labor time under capitalist conditions, Marx turns to the corvée system in Wallachia. Although the relation between peasants and boyars was originally feudal in character, Marx says that it has become incorporated into global capitalism by means of production for the world market. The traditionally limited form of feudal exploitation has been replaced by the insatiable thirst for surplus value. In the feudal corvée, the peasant’s necessary and surplus labor occur at different places and times. The peasant works his own parcel of land and harvests its crop in order to meet the subsistence needs of himself and his family, while he is obligated to work land on the boyar’s estate for a certain determinant period of time. Thus, unlike capitalist factory production, the division between necessary and surplus labor time is perfectly transparent. In “The Working Day,” Marx documents the effect production for the world market has had on that division through the passage of the Règlement organique, a law requiring the peasant to spend more and more time working the land of the boyar. Under the guise of limiting the amount of time the peasant must give to his lord, the legislation in fact expands it by means of two ruses: it identifies the corvée day with work that requires more than 24 hours to complete, and it arranges each day of corvée labor so that a part of it falls on the following day. Marx quotes a boyar, “drunk with victory” over the legislation enacted by his class, as saying: “The 12 corvée days of the Règlement organique amount to 365 days in the year.” Given the imperative to accumulate capital endlessly, the traditionally static exploitation of the peasant by the boyar becomes the boyar’s vampire thirst for the vital energies of his victim. What holds for the feudal aristocrat-become-capitalist holds for the sui generis industrial capitalist as well:

As capitalist, he is only capital personified. His soul is the soul of capital. But capital has one single life impulse, the tendency to create value and surplus-value, to make its constant factor, the means of production, absorb the greatest possible amount of surplus-labor. Capital is dead labor, that, vampire-like, only lives by sucking living labor, and lives the more, the more labor it sucks. The time during which the laborer works, is the time during which the capitalist consumes the labor-power he has purchased of him.7

Marx originally got the concept of capital as “dead labor” from Adam Smith, who, in The Wealth of Nations, defines capital as “stored-up labor.” For Marx, the object that labor produces is the activity of labor congealed in the form of a thing; it is the summation of the labor process, subject become object, time become space. But this does not in itself entail that the object is dead labor. It might be instead an affirmative expression of the creative powers of its producer, the confirmation of his or her life rather than its denial. It is only when the object is alienated from the person who makes it by being appropriated by someone else, and enters into that flux of commodities that feeds the self-expansion of abstract value in the form of money that the object becomes something dead. But since death in this case is a process, the dead must be given a semblance of life, and this can occur only at the expense of the living. Capital is inconceivable apart from the vampire thirst for surplus labor, which is simply to say, for the time that the worker has available in which to live. The accumulation of dead capital is the consumption of human lives.

In his study in “The Working Day” of the reform legislation in England that limited time at work – at first for children, then for adult women, and finally for adult men – Marx quotes testimony regarding the pottery industry in 1863, testimony made to The Children’s Employment Commission by Dr. J. T. Arledge, senior physician of the North Staffordshire Infirmary:

“The potters as a class, both men and women, represent a degenerated population, both physically and morally. They are, as a rule, stunted in growth, ill-shaped, and frequently ill-formed in the chest; they become prematurely old, and are certainly short-lived; they are phlegmatic and bloodless…”8

It was common for potters in Staffordshire to begin working at the age of seven or eight, and to put in fifteen hour shifts, six days a week, including night work.

Compare Dr. Arledge’s testimony with the account in Dr. Seward’s diary of the condition of Lucy Westenra, as related in Bram Stoker’s novel:

I was horrified when I saw her today. She was ghastly, chalkily pale. The red seemed to have gone even from her lips and gums, and the bones of her face stood out prominently. Her breathing was painful to see or hear… Then Van Helsing beckoned to me…“My god!” he said. “This is dreadful. There is not time to be lost. She will die for sheer want of blood to keep the heart’s action as it should be.” 9

Two victims of the insatiable thirst of vampires: the potters of Staffordshire, victims of the thirst of capital for surplus labor time, and young Lucy, victim of Count Dracula’s thirst for blood. Are the two kinds of thirst significantly different? “Blood is the life,” the madman, Renfield says, and it is the lives of the potters that the factory owners consume.

Marx also has his own vampire-hunting Van Helsing in the form of the workers’ movement. As we have seen, the working day under the rule of capital has upper and lower limits: the upper limit of the worker’s available physical and mental energy, and the lower limit of the time necessary to produce the value-equivalent of the worker’s wage. But the range between the two does not specify the point along the continuum that is the actual length of the working day. That determination is a result of class struggle. Much of Marx’s discussion in his chapter, “The Working Day” concerns the ups and downs of the struggle between classes that marked the progress of legislation, over a course of three decades, limiting the working day to ten hours, a major victory for the English working class. Some of the material for this discussion already appeared in his Inaugural Address as Corresponding Secretary of the International Working Men’s Association, which he delivered in 1864. The vampire metaphor occurs there as well:

Through their most notorious men of science, such as Dr. Ure, Professor Senior, and other sages of that stamp, the British bourgeoisie had predicted, and to their heart’s content proved, that any legal restriction of the hours of labor must sound the death knell of British industry, which, vampire like, could but live by sucking blood, and children’s blood, too.10

As it turned out, the Ten Hour Bill did not sound the death knell of capitalist industry in England, which was able to live with a shorter working day by lowering the real wage, given its ability to increase “relative surplus value” by cheapening, through increasing mechanization, the commodities required by the worker to survive. But Marx nevertheless regards the Ten Hour Bill as a victory for the workers movement of unprecedented historical importance. The reason is that it represents a triumph of “the political economy of the working class” over “the political economy of the bourgeoisie.” In securing passage of the Ten Hour Bill, English workers elevated the principle of “social production controlled by social foresight” over that of “the blind rule of the laws of supply and demand.”

Legislation reducing the amount of time that workers must give to their employers in exchange for a wage is a victory of life over death, of living time over dead capital. Such legislation is like the string of garlic or the crucifix that keeps the blood sucker at bay. As of late, however, the undead has been on the prowl again. As a result of a half- century of strikes and other workers’ struggles, The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 is supposed to have established the 40 hour work week in the United States. Though its coverage was never universal, and it allowed for a “reasonable” amount of overtime where implemented, it was, like the Ten Hours Bill, a triumph of the political economy of the working class nevertheless. In September 2014, Forbes Magazine reported that, according to a recent Gallup Poll, the 40 hour work week for the average full-time worker in the United States actually lasts 47 hours.11 (This, of course, does not include time spent commuting). In China, that other powerhouse of the global capitalist economy, the maximum work week is set at 49 hours. Still, according to an independent audit, the 1.2 million workers at the Foxconn factories, where Apple products are made, often put in more than 60 hours per week.12 Following the gains made by workers from the 1930s to the 1960s – in Europe as well as China and the United States – a counteroffensive has largely succeeded in restoring the political economy of the bourgeoisie. Today we sorely need more garlic and crucifixes. But, in the process of acquiring them, we must also keep our eyes out for a wooden stake that we can finally drive through the vampire’s heart.

Gary Zabel is a retired philosophy professor.

1 Voltaire. 1901. A Philosophical Dictionary, Vol. VII, Part I. Translated by William F. Fleming. New York: The Hubert Guild. 143

2 Montague Summers. 1928. The Vampire: His Kith and Kin. New York: K. Paul Trench, Trubner. v.

3 Voltaire, op. cit. 143-4.

4 Frederick Engels. 1958. The Condition of the Working Class in England. Translated by W. O. Henderson and W. H. Chaloner. Stanford: Stanford University Press. 270.

5 Karl Marx. 1963. The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. New York: International Publishers. 128.

6 Karl Marx. 1973. Grundrisse. Translated by Martin Nicolaus. New York: Vintage Books. 646.

7 Karl Marx. 1976. Capital, Volume 1. Translated by Ben Fowkes. London: Penguin Books. 342. 8 Karl Marx. Ibid. 355. 9 Bram Stoker. 1897. Dracula. Fictionwise (Barnes and Noble). 177.

8 Karl Marx. Ibid. 355.

9 Bram Stoker. 1897. Dracula. Fictionwise (Barnes and Noble). 177.

10 Karl Marx. 1973. Inaugural Address of the International Working Men’s Association in On the First International. Translated by Saul K. Padover. New York: McGraw-Hill. 10.

11 “A 40 Hour Work Week In The United States Actually Lasts 47 Hours,” Forbes 9/1/2014.

12 “Apple’s Chinese Staff Work 60 Hours a Week, Independent Audit Finds,” The Telegraph 3/2/2015.

Gary Zabel is a retired philosophy professor.