Film Review: 9to5: The Story of a Movement

Directed by Steven Bognar and Julia Reichert. US, 2020, 85 minutes.

Available on GBH Passport and Netflix.

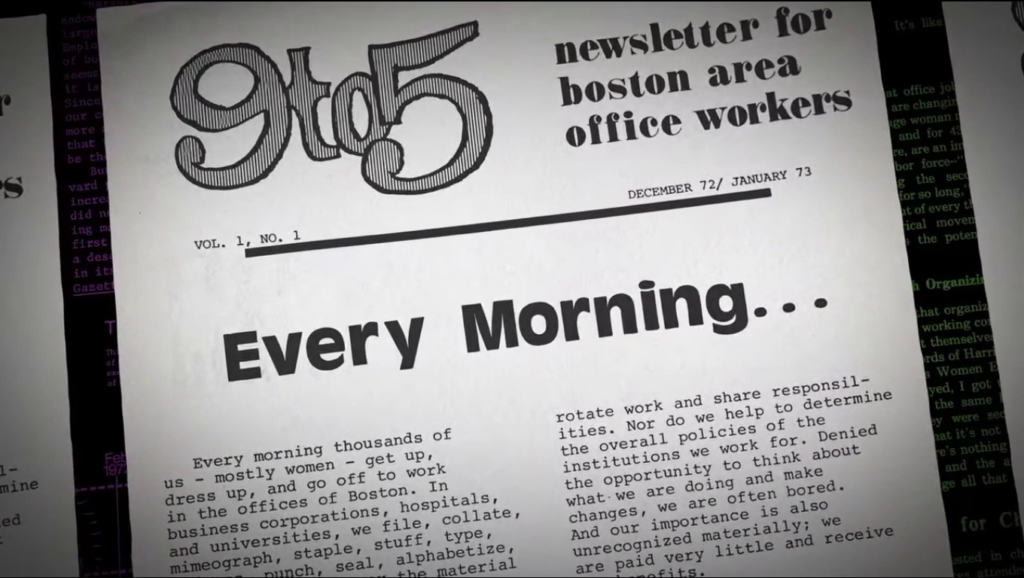

The story of the 9to5 women’s movement, which quietly entered the public consciousness with a newsletter passed around Cambridge MBTA stations in the early 1970s and eventually led to a national union run in partnership with the SEIU, illustrates that the process of labor organizing is often more circuitous than straight. And one thing 9to5: The Story of a Movement does really well is report an instance of that process without taking many shortcuts.

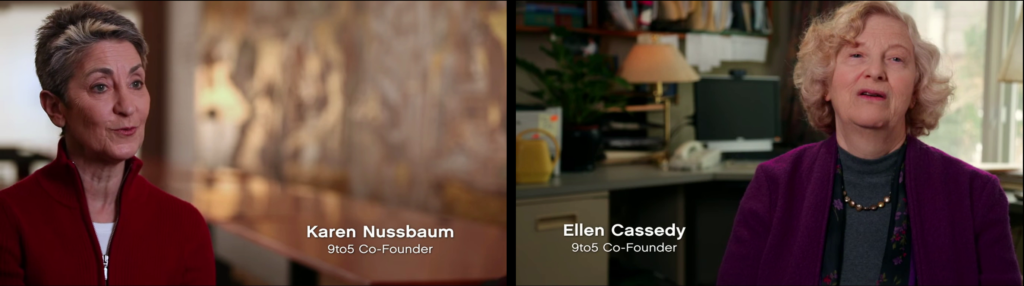

Directed by Steven Bognar and Julia Reichert, the feature is led by onscreen interviews with the co-founders of the original Boston organization, Ellen Cassedy and Karen Nussbaum, who explain in fairly precise detail how their era’s oppressive professional cultures led them to found an informal collective (initially the Harvard Office Workers’ Group), which led to a newsletter (initially the 9to5 Newsletter for Boston Area Office Workers), which led to a more formal collective with offices at the YWCA (initially Boston 9to5), which led to the formation of the SEIU Local 925 union for Boston-area office workers (established in 1975), which led to the formation of the SEIU District 925 union for office workers nationwide (established in 1981), with every step of that done “to improve conditions for women employed by banks, publishing houses, insurance companies, colleges and universities, and other major employers” (that line’s quoted from Harvard’s Schlesinger Library, where many archival collections related to Boston 9to5 now reside—in case any readers want to research further).

By pairing Cassedy and Nussbaum’s measured recollections with more worker interviews and sharp archival finds, Bognar and Reichert’s 9to5 accomplishes the significant feat of condensing and synthesizing the movement’s history without sacrificing all the little nuances and granular details that make it worth telling in the first place.

But historical reportage isn’t 9to5’s primary focus. The movie begins with faux-industrial film effects laid over footage depicting 60s and 70s clerical workers, like a video made to instruct the viewer how to do a job. And in a sense, that’s actually what it is. Bognar and Reichert, in collaboration with editor Jaime Meyers Schlenck and the rest of the crew, get into the deep procedural details of 9to5’s organizing history not just for the sake of the history itself but also to pass on battle-tested and ostensibly replicable knowledge about how this specific labor movement got started. And so the film gets beyond easy signifiers and soundbites to be more genuinely edifying than most of its peers in the contemporary journalistic nonfiction genre. Like in one scene where a speaker describes her group’s rigid scheduling, expansive outreach efforts, and food programs while claiming that “you weren’t being a good organizer if you didn’t have… like three lunches a day for ‘chrissake”—and the film’s editing actively supports her statement, adding relevant archival images and commentary from a labor historian to complete the argument. Which is admittedly rather propagandistic, but doesn’t make the message any less wise.

To get deeper into 9to5’s formal choices… well, put it this way. Among the eternal questions of nonfiction film is, should revolutionary movies be formally radical or should they be formally accessible? And 9to5 comes down on the accessible side. It’s made in a mass communicative mode—there’s not a single composition or cut that’ll stick in your craw. Subtopics are divided into clearly discernible chapters—sometimes even with complete fades in between, like for a commercial break. There is granularity and nuance in the film’s treatment of history, but no room for structural complexities or dialectic ambiguities. It’s not quite an industrial film but does occasionally read like an instruction manual.

The subtitle is The Story of a Movement, but the framing is more like The Story of a Union. That puts 9to5 right in line with many other films by co-director Julia Reichert, who has worked in a variety of genres and modes across her 50 years of professional filmmaking, and has unified those works by constantly investigating contexts of labor and capital—resulting in a number of significant cinematographic historical records like Union Maids (1977), The Last Truck: Closing of a GM Plant (2009), and now 9to5. Reichert’s collaboration with Bognar goes back to at least the early 90s, when he was credited as the associate producer on her undistributed fiction feature Emma and Elvis (1992), and the pair have been directing films together consistently since the 2000s, last completing the more observational nonfiction feature American Factory (2019) and the mid-length Dave Chappelle monologue film 8:46 (2020), the latter of which ranks among the very few American movies released last year to accurately record the temperature of the time.

Speaking of mass communication, even 9to5’s pop culture references are kept to household names. Clips are included from Mad Men (2007-15), and of course from the Hollywood movie 9 to 5 (1980), which actually was directly inspired by producer/lead actress Jane Fonda’s own friendship with Nussbaum. And the reason that it’s radio hits and Mad Men as opposed to let’s say excerpts from The Best of Everything (1959) is because 9to5: The Story of a Movement is quite frankly a very savvy movie, and thus knows that propaganda requires a little pop. Bognar and Reichert aren’t showcasing 9 to 5 (the song and movie) to Hollywoodize the story of 9to5 (the collective), but they are showcasing 9 to 5 (the song and movie) to familiarize their presumed general audience with the idea of collectivism and unionization in the workplace. Meaning the end goal isn’t self-aggrandizement or starfucking, but real labor activism—brief animated segments even literally illustrate topics like “How to Organize” and “How to Unionize,” complete with checklists. So there are passages where the film plays like a Powerpoint, but only because it’s truly committed to function over form.

Labor activism defines 9to5, but isn’t necessarily what makes it engaging. Which poses the question, what does it have for the already converted audience? First, it’s a vital piece of previously unreported Boston history, correctly prioritizing specific details over generalized platitudes. Second, the editing’s clean and intuitive enough to pursue that piece of history across other regions and decades of time without losing sight of the specific people and particular motivations that started it off. And third are the interviews themselves, which are consistently delivered with exceptional ideological clarity, and in turn recall a line from one of those people that started it off—Cassedy—who says early on that “really the truth is, you get any 10 women together and [they] start talking, and that’s enough.” She was referring to organizing, but the statement probably applies equally well to nonfiction film. And by that measure, 9to5 provides more than “enough.” [★★★]