This article is the first in a series on conditions and activism at MCI-Framingham that will be published by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism throughout 2021.

Ms. Lee

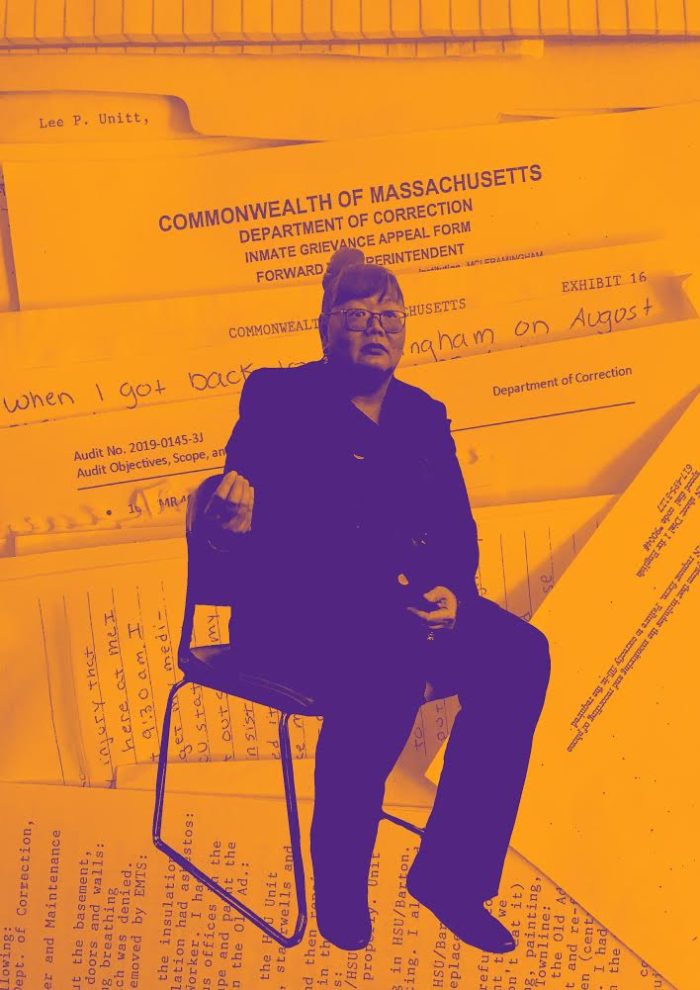

On a particularly warm day in April 2019, Lee Peck Unitt wrapped a six-year-long sentence at the oldest women’s prison in the country. With the trunk of her son’s car teeming with Bankers Boxes full of affidavits, she made her way home to Methuen, Massachusetts, with a mission.

The affidavits—sworn statements of truth or, as Ms. Lee calls them, stories—are cries for help from the women still waiting behind the walls of the Massachusetts Correctional Institution-Framingham.

Not all stories made it out, she says.

Four years before her release, Ms. Lee found three of her boxes lying empty outside the double doors of the medical unit at the state prison. She believes they were ransacked by corrections officials in an attempt to silence her.

Originally from Malaysia, Ms. Lee has been a permanent US resident for 33 years. She wears her hair in a high bun, with dark straight bangs cutting just above her horn-rimmed glasses. Behind them, the expression in her eyes is dignified and angry as she speaks about how strenuous gathering and retaining physical evidence of her allegations against the prison had been.

In her measured voice, Ms. Lee told us that the emptied boxes had contained meticulous accounts of how incarcerated women described life inside the state prison. The accounts included unanswered pleas for medical care, appeals challenging disciplinary sanctions imposed by prison authorities, and reports of harassment, negligence, and unsafe living conditions at the corrections facility.

Obtaining the materials had been no small feat, and the loss of even a few was infuriating to Ms. Lee. For years she had spent the hours between count times, chow times, and shower times in the prison’s law library reading up on state regulations as they pertained to incarcerated people. She used this knowledge to collect detailed evidence of how her rights, and those of the women around her, were being infringed upon by corrections authorities.

The stories of the women of MCI-Framingham—whether they were told through written and signed affidavits, timed prison calls, or impassioned conversations in kitchens and cafes—reveal a culture of neglect and abuse at America’s oldest women’s correctional institution. However, embedded in those stories is also the perseverance of people who have struggled, both, to improve conditions behind the hard walls of prison, and to rebuild upended lives after release.

The fallen

Heading west to MCI-Framingham from Boston, the drive is quaint and winding. Horses and cows stroll the hills; not even the haunting patch of the Sherborn Cemetery on the way prepares for the precipitous sight of barbed wire.

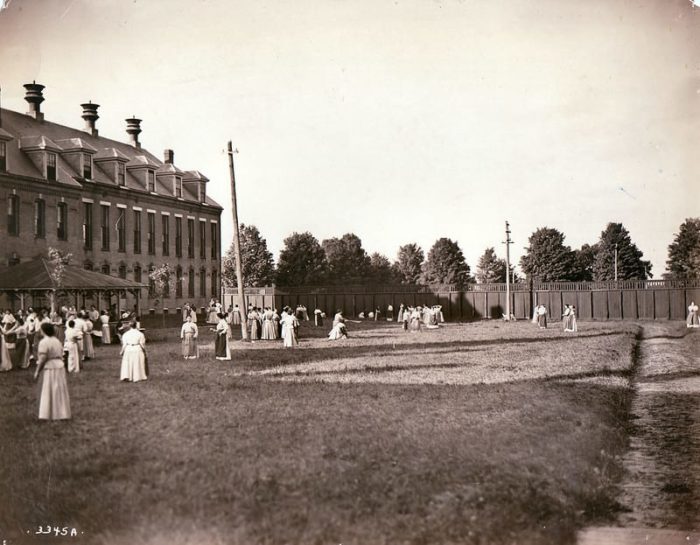

Opened in 1877 as the Sherborn Reformatory for Women, this is the oldest all-women’s prison still in operation in the U.S. At its inception, prison reformers saw Sherborn as an opportunity to implement a more gendered mode of punishment rather than relegating women to isolated corners of male-dominated institutions.

Followers of Quaker carceral reformer Elizabeth Fry believed “fallen” women could be redeemed by becoming finer housekeepers. The original architectural model of the prison saw cells replaced with “cottages,” equipped with living rooms and kitchens where women could participate in cooking, cleaning, sewing and similar “feminine pursuits.”

Yet, as the US prison system evolved over the 20th century, shaped by structural racism, the war on drugs, and tough-on-crime policies of the Reagan-era, “female” prisons like MCI-Framingham began to look more like “male” prisons: overcrowded, confined, and severe.

Until two years ago, Framingham crammed people held pretrial—many detoxing from heroin; convicted of drug possession or distribution, or crimes linked to poverty and homelessness—together with women who had been sentenced for decades, and some for life. With more than 800 people held there, the population was at double that of what the facility was built for.

In 2016, the Department of Corrections began moving women out of Framingham into wings of male facilities in Chicopee and Norfolk. Today there are just under 200 people living inside the cluster of dilapidated brick buildings and decrepit cottages that constitute MCI-Framingham. Toxicology reports from 1980 to 2018, which were obtained from the DOC for this story, revealed that the cottages—named Algone, Townline, Brewster, and Pioneer—contain dangerously high levels of asbestos, black mold, and polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, a highly toxic industrial compound.

We asked public health physician David O. Carpenter to look over the reports on MCI-Framingham. The New York-based toxicologist said exposure to PCBs and black mold can be linked to a number of severe health complications, including chronic conditions that weaken the immune system. “There certainly are very elevated levels of polychlorinated biphenyls [at MCI-Framingham], and there is an enormous body of information on health effects from exposure to them,” he wrote in an email. “That includes respiratory and menstrual disorders, but mold also is a significant source of respiratory problems.”

A 2019 health inspection confirmed the persistence of severe health hazards at Framingham, identifying 107 repeat health and safety violations, including poor sanitization standards, mold, and improper medication storage.

More recently, the state audited the prison, raising further issues pertaining to healthcare and inadequate programming to help individuals find employment and take control of their health records after incarceration. The auditors were unable to officially complete the report, however, because the physical copies of the medical files needed for inspection were so contaminated with black mold that they were deemed unusable. A former services worker said that the files had been stored in a dingy corner underneath a set of stairs where a black mold infestation took hold.

“If these medical files had been available, it is possible that our audit procedures might have identified further issues,” the audit states.

Catching up

Connie Garcia was detained behind the walls of MCI-Framingham twice, spending close to two decades at the prison.

She wrapped her second sentence before Ms. Lee did, but the women briefly shared a cell when their stints overlapped. On a wet, icy day in January 2020, more than three years after their time together at the state prison, they excitedly finished each other’s sentences at a diner in Dorchester, MA where Connie and her family live.

The two women talked about Mama Lou, an elderly Black woman in her late 70s who had been incarcerated at the prison for life. They talked about their families and children, about how hot the cells got, health problems, old friends, and old foes. They caught each other up on the women they knew who are now deceased, some due to a heroin relapse after release, others to illness in custody, and a few to suicide. “They just couldn’t cope anymore,” Ms. Lee said.

Connie struggled with the deterioration of her own mental health while she was incarcerated.

“I had a nervous breakdown.” she said. “I had a nervous breakdown because I was young and they gave me ten years. My best friend died there. She committed suicide.”

Instead of receiving treatment, Connie says she was removed from the general population and placed in a solitary cell where she was “four-pointed,” a colloquialism women use to refer to an officer restraining their arms and legs so they are pointing in four directions. She was then placed on “eyeball,” where an officer watches the person in question for a 24-hour period.

“They tie you up, handcuff you, your feet and your hands and video you. It was like animal treatment,” Connie said.

“They gave you paper jammies back then, and tied you up. If we are suicidal, why are you treating us like we are animals?”

After her release from solitary, Connie was prescribed a heavy dosage of psychotropic drugs and antidepressants for the remainder of her first sentence which ended up being 13 years long. She would keep taking them for a decade after, until she went back to prison in 2014.

In November, a two-year investigation of the Massachusetts DOC released by the U.S.Department of Justice showed that the DOC routinely violates the Eighth Amendment rights of incarcerated people by failing to provide adequate health care and exposing incarcerated people to conditions—such as long stretches in solitary confinement—that can lead to self-harm or death. Connie said she is only one of many people whose rights were violated.

“If we have mental issues or problems, they should help us, not lock us away in a room,” Connie said. There was a bustle in the restaurant as a family was seated at a nearby table. A server came with fried okra. Connie and Ms. Lee continued their conversation.

A little over two hours later, the women hugged and said goodbye. Connie gave Ms. Lee a copy of her medical records and a stapled stack of signed affidavits about her respiratory and mental health issues. The older woman, a jailhouse lawyer, slipped the papers in her handbag as they parted ways.

Connie’s affidavits detail the years she worked as a “special project worker” at the prison, where she and other women scraped and stripped walls and windows tainted with asbestos and PCBs with no protective equipment. “I had a bad cough. I still cough. And I had nose-bleeds back then after doing that every day. We needed masks or something to protect us at least.” Connie began using an old T-shirt as a makeshift face covering to keep from inhaling toxic construction dust.

Her documents are only a handful of the hundreds that Ms. Lee has collected from the women of MCI-Framingham since she started assembling her lawsuit against the prison.

Ms. Lee said Sergeant Jason Allain would stop her in the hallway and demand to inspect her folder as she returned from the law library. According to a 2016 affidavit, signed by three other women who accompanied Ms. Lee to the law library, the women were told, “You can only be in the law library if you have a lawsuit.”

A terse back-and-forth of letters between Ms. Lee and then-Superintendent Allison Hallett suggests prison authorities also tried to curb the number of grievances Ms. Lee could file by altering the number of days in a week from seven to six so that filing at the end of the week would push her over the DOC-mandated limit of five grievances per week. In response, the jailhouse lawyer invoked the Merriam Webster definition of a week, verbatim.

“I was really annoying,” Ms. Lee confessed, adjusting the thick frames of her glasses. “They were annoyed by me because I wrote grievances for everything. I always left a paper trail. And they hated me because the women trusted me.”

This paper trail would form the evidence in three lawsuits—Lee P. Unitt v. Luis Spencer 2014, Lee P. Unitt v. Daniel Bennett et al. and Unitt v. Bissonette. The Bennett and Bissonette were first filed cases as one large complaint Ms. Lee, who was representing herself at the time, but were bifurcated into distinct cases by the presiding judge by 2018 —Unitt I (Bissonette) outlining medical care and excessive force, and Unitt II (Bennett) unsafe living conditions.

Today, Ms. Lee and her attorney have faced numerous challenges, including repeated “motions to dismiss” by the DOC, but they are forging on, said attorney William Keefe. Their trial date is set for spring 2021.

“[Lee] is smart,” her lawyer observed. “There is an administrative law handbook related to Massachusetts that is over a thousand pages long. She knows it all. She can quote it page by page.”

The 55-year-old woman is seeking damages of up to $150 million, along with categorical changes to the facility’s buildings and the way incarcerated people are treated. Ms. Lee’s lawsuit is the only one currently proceeding in Federal Court against the DOC, but her attorney believes this one is “a little bit different” from other prison litigations.

“I don’t think we have seen, in prior Massachusetts cases, evidence of hazardous conditions in prison as Lee has demonstrated,” he said. “We are optimistic about the outcome.”

Yet the process of gathering evidence—and holding on to those documents while in prison—was not easy.

On April 16, 2015, the day Ms. Lee’s motion was due, she first found her legal documents missing. This time, from a small locker all state prisoners are legally permitted to keep their personal belongings in. Representatives from the DOC, including then-Superintendent Lynn Bissonette, have denied all knowledge of rifling through Ms. Lee’s possessions. Ms. Lee, however, remains resolute in the truthfulness of her allegations.

Email correspondence produced by the DOC in Unitt v. Bennett, et al reveals instructions from Superintendent Lynn Bisonnette to search Ms. Lee’s cell for legal documents in case she was holding more than the 1 cubic foot of paperwork permitted—this policy, however, was never enforced before Ms. Lee’s lawsuit, according to the affidavit of an incarcerated woman named J. Snyder. Lynn Bisonnete’s email included a disclaimer that the officers ought to search “several” other cells so “we are not just doing this with her. Let me know what you find and what the outcome was.”

In response, an Officer Mckenzie is stated to categorize all contents of Ms. Lee’s legal documents, a suggestion that he has gone through them. “I am almost done sorting through the box of Unitt’s paperwork. Do you want to come over to my office and look at what I have?” says another email from an officer to the Superintendent.

When Ms. Lee finally left the prison four years later, it would be without thirty-six cubic feet of her legal documents. That’s the size of a large refrigerator. What she did salvage was only about one-third of all the papers she had accumulated over the course of her sentence.

The papers she brought out came in several trips. In stacks, many and tall— wrapped inside trash bags, taped several times over, loaded in car trunks. They came from her cell, from footlockers, from manila folders, from hundreds of women who lived with her in the crumbling buildings of MCI-Framingham.

Spread like wildfire

By December, Massachusetts—like the country—reached a record number of new COVID-19 cases. Incarcerated people, including those at Framingham, are at extremely high risk of infection due to crowded living conditions, poor healthcare, a lack of autonomy over their own medical decisions and access to information.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, some of the largest clusters of COVID-19 have been linked to jails and prisons. Although vaccinations show promise, for many they will come too late.

“In this institution, if one person gets it, it is going to spread like wildfire,” said Zeno Williams, who has been serving a life sentence at Framingham since 2003.

As some were relegated to days at home in the early months of the pandemic—sans restaurants and movie theaters—the women at MCI-Framingham entered a strict 22-hour-a-day lockdown. Educational programming ceased, the use of the law library and gym was prohibited, jobs were suspended, and family and friends were no longer allowed to visit. At times, incarcerated women could only leave their cells for thirty minutes a day.

The unsafe conditions Ms. Lee identified in Unitt v. Bennett —“oppressive heat, lack of ventilation, and exposure to dangerous airborne particulates like PCBs, asbestos, and black mold”— have only worsened as the disease rages on. Existing health conditions have intensified during the past months as resources have dissipated.

Zeno is one of the people Ms. Lee collected letters from at MCI-Framingham.

“Not having medical appointments puts a strain on all of us,” Zeno said. She explained that incarcerated women can still request that a nurse come to their cell, but they have to explain their medical issue through the cell door so the entire hall can hear.

“But like me, if you are in dire pain and need help, what other choice do you have?” she said. Zeno is immunocompromised and has multiple health complications. Like Connie, she was a “special project worker” tasked with removing toxic chemicals without any protective gear.

“I see the girls who are helping us clean,” Zeno said, referring to other incarcerated women disinfecting common areas. “I tell them how proud I am and how grateful I am. No one is going to help us but ourselves.”

When numbers in Massachusetts began to rise, Zeno began sleeping with a handmade mask and helping her cellmate translate COVID-19 testing paperwork.

When numbers in Massachusetts began to rise, Zeno began sleeping with a handmade mask and helping her cellmate translate COVID-19 testing paperwork.

“Since the form only came in English, I had to explain it to my cellmate,” she said. Zeno said when she sees corrections officers not wearing masks or washing their hands, she feels afraid for the old and sick.

Before the pandemic, she worked as a runner in the Health Services Unit, where she collected trash, cleaned rooms, and distributed supplies to women in the unit, some who live there permanently due to terminal illness.

Zeno said the loneliness experienced by people confined to HSU can feel worse than solitary confinement. She said women in the prison often do not trust medical staff because requests for help often go unanswered or people who need care are forced into isolation.

“A large amount of women, including myself, declined the [COVID-19] test out of fear that we could get a false positive and be locked away for it,” she said.

There are currently major outbreaks at multiple DOC facilities in Massachusetts. Beyond the risk posed by the virus, the lack of structure and human contact has had a significant impact on the overall well-being of those incarcerated.

“We are not allowed to make ourselves something to eat on our half-hour out,” Zeno said. “And we know we aren’t getting out anytime soon. The lack of fresh air is making us worse.”

Grassroots organization Families for Justice as Healing called for the liberation of all incarcerated women in addition to the creation of community-based alternatives to prisons. The group organized multiple car protests outside of MCI-Framingham.

“There must [have been] like 50 cars,” Zeno said after a demonstration in May. “This is beautiful. Even a dog came.”

Prisoners’ Legal Services, a legal advocacy organization, is also urging for the release of immunocompromised people to mitigate the risk of COVID-19 in Massachusetts prisons.

“Those who may not have a place to go could be housed safely in shelters,” Elizabeth Matos, executive director of PLS said. “We have the resources to house people. What is lacking now is the will to do it.”

Along with public health experts, Suffolk County District Attorney Rachael Rollins and Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley have implored the administration of Gov. Charlie Baker to take measures to reduce the prison population.

“With the stroke of a pen, Governor Baker can release individuals who pose no risk to their communities but are at great risk themselves,” the congresswoman said at a press conference in November.

Despite the peril of the current moment, Ms. Lee’s lawsuits and documents show that life at MCI-Framingham was inhumane long before the pandemic. Pleas for medication, for a table fan, for a milk-crate so a woman with severe arthritis could climb up to her top bunk without pain, and many more pleas for assistance came through hundreds of “sick slips”—forms prisoners fill out to request a trip to the nurse. At MCI-Framingham, sick slips cost three dollars apiece, many of which the women say go unanswered for months on end.

“It’s very typical that people would put in a sick slip, and another sick slip, and another sick slip, until they get seen,” Elizabeth said. Included in Ms. Lee’s documents are stacks of contested sick slips from the women she lived with.

“I have been waiting for my top dentures for six years and my bottom dentures for four months now. Can I please get some teeth?” pleads a hasty scrawl.

“What is her life?”

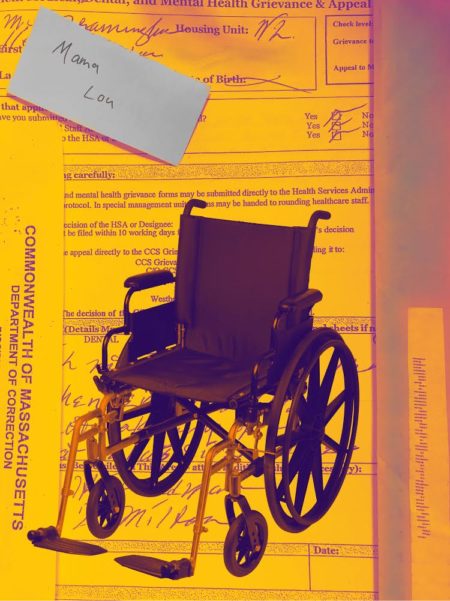

The plea for dentures is a medical grievance filed by a woman who had been serving a life sentence since 1981. Known to the thousands of women who came in and out of the prison as Mama Lou, prior to her incarceration she had supported herself and her son as a sex worker in Boston.

Mama Lou passed away in 2018. Yet many of the women we spoke to shared distinct memories of her impact on life at the prison, which they shared with us. In the ’80s, she would shell out $70 for a pair of yellow, lace-up Timberland boots from the prison commissary and wear them religiously as her years inside MCI-Framingham melted into decades. As she entered old age, a set of “cheater” eyeglasses hung around her neck and an extra yogurt she pilfered from the chow hall sat in her pocket when she slowly made her way around the compound.

The women we spoke to recalled how Mama Lou became more and more eccentric as the years passed, spraying her cellmates with cleaning supplies while they slept and accusing them of masturbating under their sheets in a decades-long ploy to have her own cell. Yet even the most disgruntled of her cellmates would say she was a sweetheart at her core.

Women tend to recreate family structures in prison—daughters, moms, grandmas, sisters, and aunties. The average age of incarcerated women at Framingham is 40, with the youngest being 19 and the oldest 75.

When Mama Lou slipped and broke her hip in a kitchen injury resulting in chronic MRSA infections, she became relegated to a wheelchair. If she liked someone enough, she would ask for help maneuvering around the prison grounds or making her way to the toilet. But she never asked for assistance sneaking down to the kitchen late at night to pinch some ice cubes to bring back to her cell. Ice cubes are in high demand at MCI-Framingham.

Nicole Murphy, who considered herself one of Mama Lou’s favorite cellmates, recounted bittersweetly how the older woman would fall asleep on the toilet under a strong cocktail of antidepressants she had been on for decades since her incarceration.

“It made me irritated because I’d call all night for her to get off the toilet, ’cause I had to pee too,” Nicole said, receiving nothing but sedated mumbles in response. “I kept thinking, ‘What if this was my mom or grandma, you know?’ It’s so sad to think—‘Why is she on these meds? What is her life?’”

More than half of the women at MCI-Framingham are on psychotropic medications, and 75% have open mental health cases prior to entering prison. Incarcerated women are twice as likely to be prescribed psychotropic medication as their male counterparts.

For years, a few corrections officers would chip in for Mama Lou’s favorite food item on her birthday—a meatball sub—that would be snuck in on a night shift and would reach her cell. Other than formerly incarcerated women who knew her and would send her $20 or so every once in a while, Mama Lou had no visitors or phone calls that anyone knew of.

In 2012, after she broke her hip, Mama Lou filed an official complaint with the Commonwealth about unsafe conditions in the prison along with a disabilities claim later that year. The older woman was not known to take legal action against the authorities and until then had stuck to occasional grievances about room temperature, roommate grumbles, and water quality. In response, the Commonwealth installed a ramp and railing in the spot where Mama Lou fell.

But Mama Lou paid a steep price for her complaint. She lost the sympathy of guards and began to face what incarcerated women say is the biggest punishment for speaking out in Framingham—retaliation. Women we spoke to said Mama Lou’s doctor’s visits began getting postponed, her grievances went unanswered and her sick-slips ignored.

In one complaint, Mama Lou described how her gums were beginning to grow in on broken chips of teeth, causing her immense pain. She asked to be fitted for dentures and for pain medication so she could eat—a steady diet was needed to manage her diabetes.

“Mama Lou had been there for mad years. I had known her for mad years.” Connie said. “They were not treating her right.”

Mama Lou’s back-and-forth with Superintendent Alison Hallet reveals letters from prison officials stating her heart was too unstable for dental surgery. But no concrete plan was given to manage her cardiac symptoms so she could be scheduled for the operation. Mama Lou became so aggravated that she finally reached out to Ms. Lee through women who knew her as a jailhouse lawyer.

Ms. Lee was at the tail-end of her sentence when the frustrated veteran of the prison contacted her. She recalled having to go downstairs from her unit to meet an unwell Mama Lou at the base of the stairs, because the older woman was unable to climb all the way up. After their meeting, Mama Lou signed an affidavit describing her health difficulties and gave Ms. Lee her medical grievances,sick-slips and drug prescriptions as a part of the case against the Massachusetts DOC.

The lawsuits may ultimately force change at the prison, but it will be too late for Mama Lou.

Relegated to the far corners of MCI-Framingham, ill and without teeth, Mama Lou became weaker and weaker. Three weeks after her last petition for teeth in October 2018, she died quietly in the prison’s Health Services Unit.

Shelby is a graduate of Emerson College. She has been published in The Boston Globe, The New England Center for Investigative Reporting, and Spare Change News. She is passionate about covering prison health care and stories related to incarceration.

Twitter: @grebbin_shelby | Email: srgrebbin@gmail.com

Isha is a graduate of Emerson College, with a degree in Broadcast Journalism. She has interned with Boston-25, Channel 5 and the Belfer Center - all of which honed her attention in on long-form storytelling - both in TV news magazine format, as well as written narrative.

Twitter: @IMarathe | Email: isham7461@gmail.com