Blanket Statement No. 2: It’s All or Nothing

By Jodie Mack. US, 2013, 4 minutes.

Screening at the Brattle Theatre as part of “Jodie Mack: Cabinet of Curiosities”, tonight, July 20, at 7pm. Streaming online at Vimeo, see jodiemack.com for more.

Before the print edition of DigBoston was suspended almost exactly three months ago, I had planned to write a review about the Wasteland films by Jodie Mack up to and including the latest entry, Wasteland No. 3: Moon, Sons (2021), which is currently installed at the center of the New England Triennial 2022 at the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum in Lincoln. I still hope to finish and publish that article, given the show will continue for another seven weeks or so. However what’s got me back here at digboston.com, after yet another of my pointless monthslong breaks from digital publication, is the opportunity to write a diary entry on an earlier Mack film, Blanket Statement No. 2: It’s All or Nothing, a movie that I’ve returned to constantly since I first saw it at the Harvard Film Archive about five years ago.

Perfectly befitting both its title and the subject of its images, Blanket Statement No. 2 has for me become the ultimate comfort movie.

I’ll start by saying, for the uninitiated, that Blanket Statement No. 2 is a properly representative example of the artist’s larger catalog, call it classic Jodie Mack. Like many other Mack films made between 2010 and her feature The Grand Bizarre in 2018 (see accompanying DigBoston interview here), Blanket Statement No. 2 presents a series of precisely composed still frames depicting textile objects edited into a rhythmic meter of mostly fast motion, fusing the definition of animation with the idea of archival to finally reimagine the energy, form, and purpose of the flicker film.

Both of the Blanket Statement films will play at the Brattle Theatre in a few hours as part of “Jodie Mack: Cabinet of Curiosities,” a program of 12 shorter films by the artist, followed by an in-person Q&A with Mack and Sarah Keller. Presented by the Revolutions Per Minute Festival (RPM), “Cabinet of Curiosities” features work from the whole of Mack’s professional career, including examples of her direct animation (All Star, 2006), her moving collages of found objects (the Unsubscribe cycle, 2010), her aforementioned visual archives of flickering textiles (including Point de Gaze, 2012, and Razzle Dazzle, 2014), and the Wasteland cycle too (which also includes Ardent, Verdant, 2017, and Hardy, Hearty, 2019).

For me the program includes at least two masterpieces of modern American cinema, those being Point de Gaze and Blanket Statement No. 2.

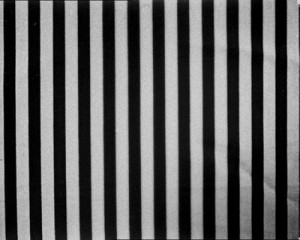

Point de Gaze is also, in a sense, classic Jodie Mack, given that it’s another textile-based animated flicker movie open to a genuinely awesome extent of interpretation, spanning across material, narrative, formal, sensorial, pictorial and subtextual grounds. Bounding through still images depicting Belgian lace (material) at rapidly varying editorial speeds (formal), Point de Gaze, which is silent, creates a light stroboscopic effect at the start and builds up to a nearly violent one at the finish (sensorial), cycling from images of bright white lace into examples of blue, orange, purple, and red (pictorial) until the momentum of the cuts finally carries it back to alternating black and white for a flickering grand finale (narrative), the whole movie foregrounding the ephemerality and fragility of the lace in a way that allows the constant transformations depicted inside the frame to reflect the state of constant transformation we all experience outside it (subtextual).

Point de Gaze is not only a supreme visceral experience of its own but also seems to encapsulate the very idea of visceral experience.

To flip that phrase, Blanket Statement No. 2 is not only a supreme cinematic experience of its own but also seems to encapsulate the very idea of cinematic experience.

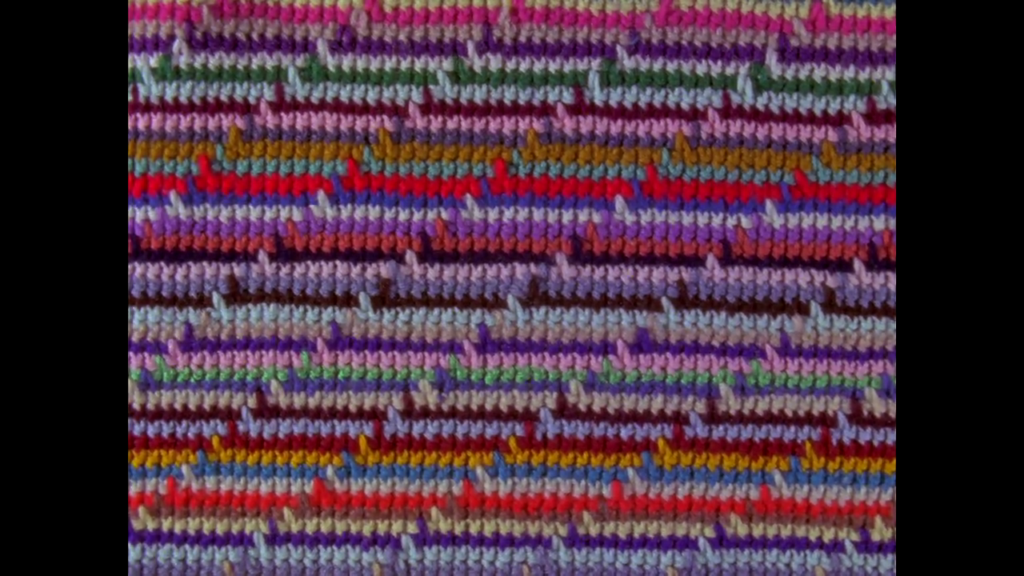

Blanket Statement No. 2 is an even more precisely controlled film, as it depicts more precisely aligned materials and patterns. The subject is crochet textiles, which Mack photographs at an exact range of varying distances. The film begins with the most close-up composition, featuring about 10 horizontal lines of individually colored fabric loops (as seen above), while simultaneously establishing the fastest possible rhythm by filling every frame (or every other frame?) with a repositioned or entirely different textile image. It next exhales via a sort of fake zoom out to its furthest composition, featuring about 40 fabric loops (therefore displaying more distinct endpoints for each series of stitches, as seen below), while slowing down the cutting speed toward a series of longer-held images and blacked-out frames near the midpoint. The editing pace and photographic distance then speed back up, slow back down, and so on for the remaining two minutes, continuing the artificial breathing or zooming effect until the film seems to freeze up at its finale.

If compelled to give a fine art comparison I might say Blanket Statement No. 2 is like sprinting up a stairway while staring at a series of color field paintings, complete with breaks to catch your breath.

Looking at individual frames reveals the richness of the image, right down to infinitesimal fibers. I suppose credit for that is split between Mack for the photography, and the seemingly anonymous crochet artist for the material. Additional visual allusions come to mind too. Personally I’ve always perceived a reflection of analog static in Blanket Statement No. 2, the fuzz of the fabric matching the fuzz of untuned television noise. And others have pointed out the similarity to glitch art or 8-bit aesthetics, which is certainly supported by the freeze up ending.

Yet what’s possibly most crucial to the film’s visual power is the base level choice to utilize a fabric that carries primal associations for a large swathe of viewers. Perhaps now it’s me who’s projecting, but the images of Blanket Statement No. 2 remind me of my paternal grandparents’ house, and so I imagine they remind you of someplace too.

Also embedded deep in the stitches of Blanket Statement No. 2 is the mechanisms of film projection, another increasingly historical association that carries memories, nostalgia, and meanings of its own. For instance when put into frame by frame motion, the horizontal lines of these individually photographed textiles create the perception of vertical movement, like a rhyme for the motion of a film print through a projector. Meanwhile the ramping speed and use of blacked out frames between some images furthers that same formal idea, calling back to hand crank projection methods and the variable frame rates or blank interframe spaces it often produced.

The projection connection is officially confirmed, however, not by image but rather by soundtrack.

“The direct relationship between sound and image in Blanket Statement No. 2 intentionally stems from the film’s production technique. The images are actually making the sounds,” Mack explained to FilmLinc Daily before the film screened at NYFF 2014. “Shot on a Super-16mm camera, the images of the blanket actually extend into the soundtrack portion of the film—creating an indexical relationship between image and sound… The ‘throbbing propeller’ soundscape comes from the sound of the frame lines running through the projector.”

It occurs to me that a throbbing propeller soundscape further situates Blanket Statement No. 2 in a specific film-historical lineage. It reminds me, for example, of the synthy reverb-heavy score of Tony Conrad’s seminal though not original flicker film, The Flicker (1966), which emits a similar drone of rapid low range tones across its running time.

Perhaps even moreso Blanket Statement No. 2 reminds me of Conrad and Beverly Grant’s film Straight and Narrow (1970), another flicker film that projects static lines at high speeds to create a hallucinated perception of vertical (and horizontal) movement.

Additionally both The Flicker and Straight and Narrow, like much of Conrad’s film and music work, seem directly influenced by experimental musician John Cage—who Mack cites herself in the same FilmLinc Daily interview as being central to Blanket Statement No. 2’s underpinnings.

“I’ve had an interest in strategies of image/sound synchronization for many years,” she continued after the prior quote, “But, it wasn’t until I realized exactly how much influence Oskar Fischinger had over the development of John Cage that I understood how important these types of experiments were: not only for the development of experimental animation but also perhaps for the entire catalog of 20th-century experimental music… So, the aforementioned indexical relationship between image and sound that plays out in Blanket Statement No. 2 seems possibly the purest form [of] A/V combinat[ion].”

In Blanket Statement No. 2, which is available to view as a digital file on Vimeo, there is a slight lag between the images and the audio they seem to create. Cued by the first sounds appearing roughly one second after the opening title card, we come to understand that each image features corresponding audio that plays very shortly afterwards—meaning the sounds of the film are echoes of its visuals, in both frequency and timing.

Blanket Statement No. 2 thus becomes not just a comfort(er) movie but also a concert movie where the musical artist is the film object itself.

Part of the reason I draw a distinction between the digital file, which I’ve watched at home and with friends countless times across the last five years, and the 16mm print, which I saw just the once at Harvard five years ago and greatly look forward to seeing once again at the Brattle in a few hours tonight, is because there’s an immense gap between the experience of the film across the differing formats.

“I think a lot of my shorter, more stroboscopic works kind of die on video not because of the image quality as much as because of the mechanics of the projection—the intermittent stroboscopic of a film projector vs. the refresh rate of a video projector,” Mack explained to me during our interview a few years ago.

Indeed with Blanket Statement No. 2 and some of the other Mack movies showing this evening, there are stacked up levels of spectatorial effects that really only come through when they’re seen projected theatrically on film. The “mechanics of the projection” and the “intermittent stroboscopic of a film projector”—to borrow the phrases—become central in our viewing of the picture show, blending into and radically changing the movies from what they seem when they’re seen online or from video files. And this is true not just in a general every screening is special and unique sort of way, but also in more direct experiential and interpretive terms that are specific to each individual film.

For instance when projected from a 16mm print, Blanket Statement No. 2 creates even more connections between its own film text and the general experience of projected cinema, beyond the links made apparent in the digital copy described above… we strain to discern the distinction or interaction between the fine tiny fibers of the crochet and the fine tiny grain of the film print… we hear a more authentic projector-backed audio track… we see how the natural blips, skips, and bumps of projected images line up with Mack’s particular editing rhythms and formal allusions… we are forced to directly consider the qualities of the actual film print itself, to see all its developing imperfections and scratches, and to engage with the clear thematic connection between the inevitable degradation of the print, the inevitable degradation of the many textiles it depicts, and the inevitable degradation of all other things… and we may even think about the properties and possibilities suggested by the materiality of the print itself, especially after it’s been removed from the projector, at which point it becomes an unmoving and possibly even archival-level photographic record of the materials depicted within each frame, in one last tantalizing aftereffect of Mack’s chosen form.

Every loop of Blanket Statement No. 2 leads back to some kind of reflection on the collective human tendency to congregate and view light on a screen.

Fealty to original formats in favor of virtual alternatives is by no means a matter of All or Nothing, not for art, articles, or much of anything else, but a movie like Blanket Statement No. 2 plays like proof, as clear as the eye can see and as sure as the ear can hear, that experiencing images and sound on film is one thing, and experiencing the same from a digital file is another. [★★★★★]