Like most businesses, Hollywood movie studios are forever on the lookout for ways to profit off things that aren’t really their business. For example right when the US government forced the major studios to sell their ownership shares of movie theaters in 1948, those same major studios were simultaneously looking for ways to break into the television market too—with Columbia Pictures succeeding first by establishing subsidiary company Screen Gems and licensing shows like the Dupont-sponsored Cavalcade of America (1952-57) directly to broadcast networks like NBC. That wasn’t too groundbreaking back then, but from the contemporary perspective it’s probably one of the most decisive moments in the history of movies… the choice to see television not as a pesky competitor but instead as just another profit stream in a potentially endless line of them.

The ramifications of that choice ripple to date, where all remaining major Hollywood film studios aren’t even in the movie business so much as they’re just in the screen business. Even the word “major” is now something of a misnomer, given that many of today’s biggest studios are in fact mere subsidiary companies subserviently accommodating whatever multinational conglomerate owns them.

But if we’re going to keep the descriptor, let’s at least be exact about which studios it applies to. Currently there are five major Hollywood film production studios (Columbia, Disney, Paramount, Universal, and Warner Bros.), and three major Silicon Valley film production studios (Amazon, Apple, and Netflix), all with their own house styles, preferred directors and performers, and specific marketing strategies. They’re united only by a shared effort to de-emphasize theatrical exhibition right now in favor of more “direct to consumer” models controlled by their respective parent companies, like subscription-based streaming platforms.

This creates a situation where many crucial distribution choices appear to “literally [make] no sense” even to professionals hired to make sense of the movie business, because those professionals are interpreting the business in outdated 20th century terms where good box office and maximum theatrical revenue equals best practices. That reading misses that commercial American movies have lost stature even within the industry that produces them (just as they’ve lost stature with the public they’re made for) to such a degree that they now mostly exist as brand-name support beams for larger corporate strategies (or even just as a means to collect more consumer data).

For instance Universal, which is owned by Comcast/NBC, has spent the past year openly exploiting the effects of the pandemic to drastically reduce the contractually obligated lag time between a film’s theatrical release date and its subsequent availability on VOD and home video—which comes at the cost of movie theaters and perhaps even the studio’s own bottom line, but nonetheless makes perfect sense within the context of Universal being a subsidiary company that answers to shareholders primarily focused on monetizing television, the internet, and platform agnostic “content.”

Then last month news broke that AT&T is transferring ownership of WarnerMedia to the parent company of the Discovery Channel, making Warner Bros. the third of the five remaining major studios to be controlled outright by a television conglomerate. This arrangement further narrows the kinds of movies being produced by those studios (by my count the five Hollywood majors have distributed seven films based on pre-existing media properties thus far in 2021 vs. just one live-action comedy), and then also dictates the way the studios distribute those movies (usually straight to whatever streaming platform is owned by the given studio’s vertically integrated parent company, a situation that Comcast/NBC’s mid-pandemic campaign against theatrical exclusivity helped make possible).

And given all that, it’s probably best to understand the real auteurs of contemporary Hollywood movies to be not directors, writers, actors, crewmembers, producers, or even the studios releasing the films, but rather the stockholders that sit behind the parent companies that own those studios, who shape distribution slates from above to befit larger goals mostly relating to merchandising, stock prices, and mergers.

That brings us to Disney, the only studio that remains its own parent company. Everyone knows Disney movies really exist to become action figures, plush toys, video games, cheap apparel sold at big box stores, spin-off TV shows aired on the Disney Channel, theme park rides at Disneyland and Disneyworld, and then finally sequels and remakes sold for $30/pop on Disney+. For as the entire movie business devolved into the collection of subsidiary brands, Disney curated the richest collection. To wit I recently saw a photograph from “Disney Investor Day 2020” showing CEO Bob Chapek proudly standing in front of a video screen displaying all the company’s most valuable sub-companies, like the now Disney-stamped mini-studios Marvel and Lucasfilm, in an image that seemed to represent the ultimate culmination of modern Hollywood’s decadeslong obsession with “intellectual property.”

And in doing so the same image also reveals the shared philosophy basically all major studios are currently acting on: that nowadays viewers aren’t turned on by the movies so much as they’re turned on by the logos preceding them.

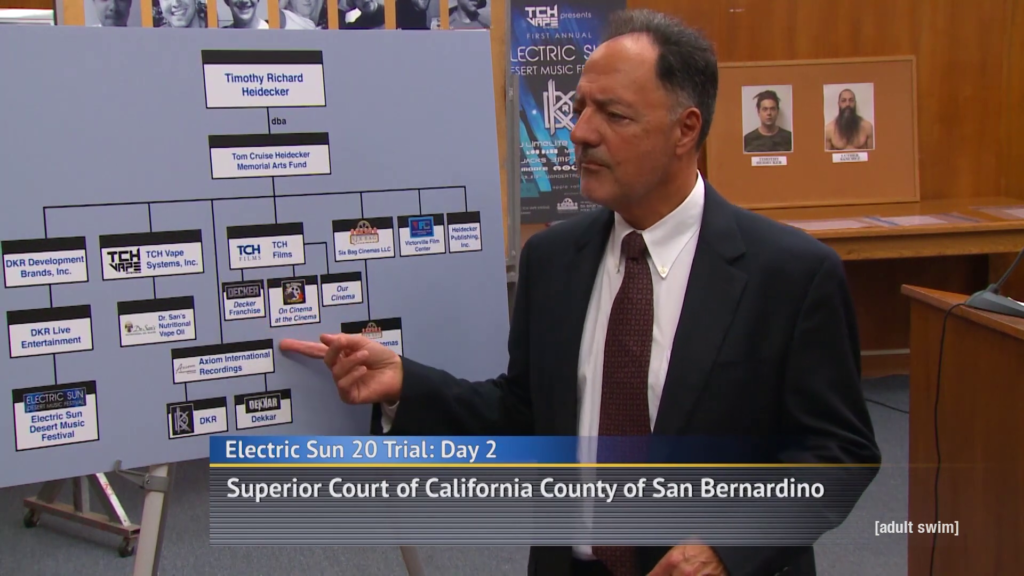

For me that chart of Disney-branded detritus brought to mind another “cinematic universe” (embarrassing phrase nobody should ever use without scare quotes) far removed from those of Marvel and Lucasfilm. Following the ninth season of On Cinema at the Cinema (2011-) came offshoot webseries The Trial (2017), a five-hour courtroom video presented in the mode of cable news coverage. At one point the prosecution introduces a board showing off the many different business enterprises operated by the defendant, which include not just the On Cinema television program but also its various spin-offs, a failed luxury movie theater, an EDM group, an illicit charity, and some “wellness” ventures, among other vestiges of vintage 2010s trends. For me that image, just as much as the one from “Disney Investor Day 2020,” precisely encapsulates the current state of movies—as mid-level priorities stationed under absurd corporate structures.

And in doing so the same image also precisely encapsulates a very specific, very pathetic, and I suspect very widely shared American dream: the desire to be a steward of intellectual property… the desire to be a major shareholder of a media conglomerate… the desire to be the kind of person that oversees a studio like Marvel or Netflix… the desire to be a parent company.

At this point a real introduction to On Cinema is probably necessary, unfortunate for me because it’s basically impossible to summarize concisely. But the essentials are that On Cinema at the Cinema is a satirical Siskel & Ebert-esque movie review program aired by Adult Swim from 2012 through 2019 and led by Tim Heidecker and Gregg Turkington, two wholly fictional characters played by actor/comedians Tim Heidecker and Gregg Turkington (from here on I’m referring to the characters and not the performers unless otherwise noted).

Ostensibly a one-note joke on hack critics that cosplay as broadcast journalists, the show immediately shifted course to deeper waters by depicting the perpetually increasing neuroses of both characters—Tim is a right-leaning trend-obsessed get rich quick type with manic and digressive tendencies while Gregg is a socially inept cataloger that defiantly wishes the show would stick to movies. But then it shifted course to entirely different waters by presenting the various multimedia projects each character does apart from On Cinema itself, all of which betray Tim and Gregg’s collective desire to fulfill the aforementioned shareholder’s American dream—resulting in roughly six hours of Tim’s DIY 24 (2001-14) clone Decker (2014-17), the aforementioned five-day Trial broadcast, a feature-length movie depicting Tim’s post-Trial run for district attorney of San Bernardino (Mister America, 2019), some music releases by Tim-fronted groups Dekkar and DKR, and finally nine “On Cinema Oscar Specials,” which usually run in excess of two hours each and provide annual centerpieces for the series’ many overlapping stories.

Meaning the narrative of On Cinema has by now achieved grotesque size, probably accounting for roughly the same total running time as the 23 films in Marvel’s “universe,” like a caricature of their bloat delivered in miniature scale.

The Marvel link is relevant not only because of On Cinema’s inherent critique of film culture, which Marvel now dominates… and not only because “the Marvel universe” was eventually folded into On Cinema itself, when both Heidecker and Turkington appeared in Peyton Reed’s Ant-Man films (2014/17)… but also because On Cinema is, much like the Marvel films beside it, a fully serialized narrative that piles higher and higher upon itself year over year. Like if pushed to assign it a genre one would probably have to call On Cinema a mock-nonfiction comedic melodrama.

Central to On Cinema’s own serialized melodrama is the emotionally antagonistic relationship between Tim and Gregg, two compulsive materialists connected only by their shared deference to the kind of magic of film-language found in Oscar broadcasts, Entertainment Weekly, old Roger Ebert reviews that include the phrase “empathy machine,” and every single recent article about people returning to the movies after the pandemic.

Motivating their conflict is that Tim delivers these bromides as a trojan horse to push politics, his own ego, and other products, while Gregg in contrast is a zealotish proselyte of the whole TCM belief system. Which makes the characters outsized representations of the two approaches that basically define current film criticism at mainstream outlets: On the one side it’s a self-promoting moral-scold egotist scoring points off simpleminded critiques of commercial products, and on the other it’s a nostalgic collector stumping for major corporations under the guise of film journalism (listen to any given film podcast from The Ringer or wherever and you’ll hear at least three unambiguous Greggisms, and probably a little bit of Tim too).

That’s all to say that watching On Cinema at the Cinema, you better understand the sort of culture that could give rise to a thing like RottenTomatoes, and that could support an industry of critics who deem movies like Avengers: Endgame (2019) to be “94% fresh.” Of course Tim and Gregg are no more discerning, offering nearly every film released by a major studio the maximum “five bags of popcorn” unless they have some kind of personal beef with one of the creators involved—a methodology not too different from how commercial movies are now reviewed at major news outlets, as illustrated by 180° reappraisals of cancelled films like [examples redacted].

Further exceptions to the five bags for Hollywood rule are usually narratively motivated and very telling: Like when Gregg reviewed Dinesh D’Souza’s independently-made pro-Trump propaganda film Hillary’s America: The Secret History of the Democratic Party (2016) at Tim’s behest and gave it low marks not for political reasons but just because “a documentary [is] not a real movie” and “doesn’t belong on the silver screen,” which he like nearly all moviegoers feels ought to be reserved for “popcorn classics” such as Star Wars sequels and James Bond movies. So if you accept my earlier proposition that some guys harbor an intense desire to control intellectual property, then Gregg is that guy: The character recently fantasy-booked the Bond franchise deep into the future, predicting that “fans will be delighted” by the Dashiell Connery-led 2047 entry The Return of 007 (which is on the one hand an explicitly absurd way to engage with the movies, but is on the other hand not something you’d be all that surprised to hear said out loud during a Ringer podcast).

Gregg’s ecstatic preview of a 2040s era Hollywood still dominated by corporate IP, neverending franchises, and rampant nepotism was delivered near the start of the 8th Annual On Cinema Oscar Special (2021), a decisive entry both inside and outside the show’s deliberately unwieldy canon. Decisive because for nearly a decade most On Cinema programs were distributed by WarnerMedia subsidiary Adult Swim—until late in 2020 when WarnerMedia’s then-parent AT&T enacted mass layoffs that left On Cinema more underfunded than usual, prompting the series to leave the network and strike out on its own in 2021. Speaking to Vulture outside kayfabe, Heidecker was careful not to ascribe direct causation, just saying “Adult Swim shut their streaming services down” and then later that “it does feel like [On Cinema] is the perfect project to try and run independently.”

Either way the result was the HEI Network, a very real subscription-based streaming platform that went live earlier this year and is operated within kayfabe by Heidecker’s character. The network launched in earnest with the 187-minute 8th Annual On Cinema Oscar Special, which like basically all works in the On Cinema project is directed by Eric Notarnicola and written by a team including Heidecker, Notarnicola, and Turkington. Or more accurately the network launched with half of what’s now known as 8th Annual On Cinema Oscar Special, because the animus between the Tim and Gregg characters required that they initially host two separate livestreams—Gregg’s on Youtube, Tim’s on HEI—that have since been lightly edited into alignment by Notarnicola for viewing in a dual projection-style aspect ratio of roughly 3.5:1 (as seen above and below).

On Cinema has always been a gleeful inheritor of the absurd public access aesthetic established by the real Heidecker’s other major collaborative project Tim and Eric, but Notarnicola’s combined dual-screen video of the 8th Annual special probably represents the height of the show’s formal (un)sophistication: Gregg’s flat-voiced selfie-mode stream is on the left (with the vibe of an abandoned mall video), and Tim’s HEI Network variety show is on the right (with the vibe of a Daily Wire live special), creating a constant sensorial overload that’s entirely appropriate for On Cinema’s central subject, which is nothing less than a study of the moving image in the age of Youtube (one that considers the Hollywood cinema, the homemade video, and how the former has malformed the latter—and its maker too).

The first hour is probably the funniest and most narratively complex part of the 8th Annual, creating fun interplay between the dual projection format and both character’s very divorced philosophies. Gregg’s stream begins with fannish monologues delivered from a Burger King parking lot (he’s currently homeless), while Tim’s plays a litany of skits depicting half-finished HEI business ventures spun off from his social circle (including On Cinema-adjacent piss-takes of Tucker Carlson, old MTV reality shows, John Krasinski’s hopecore livestream Some Good News, and the videos of Project Veritas). Thematic connections abound despite the formal disconnection, though, as both streams constantly evoke the ongoing decay of the cinematic art form: Merchandise from Universal’s apocalyptically prolific Minions series (2015-) proliferate on set without explanation, Tim mimics conservative-radio bits about the genuinely low reach of films made for adult viewers, Gregg visits the paved-over gravesite of Toto from The Wizard of Oz (1939), and it’s all composed in the Tim and Eric-derived aesthetic of incompetency to add an extra layer of sociocultural contemptuousness.

The streams inevitably cross over around the one-hour mark, obviously under the more well-funded HEI umbrella (inevitable like all the recent Hollywood buyouts). The left side goes fairly stagnant (like a shuttered division) while the HEI-branded adverskits command full priority, and the comedy suffers a bit for the formal simplification. Yet below the surface, there’s cinematic purpose to it: By sublimating Gregg’s stream into Tim’s, the 8th Annual special basically aestheticizes a corporate takeover, and reframes itself as something like a “Disney Investor Day”—or rather, as a feature-length insult directed towards the sort of film culture that would see fit to care about such things.

But it’s too easy to frame On Cinema solely in that context, as subtextually-oriented film-industry critique. So it’s necessary to stress that’s not really the case, the show is even funnier in practice than in theory. A recurring cycle of friendship breakups, grievous injuries, and tentative reunions, On Cinema is something like half-soap half-sitcom—as in most Hollywood movies, formula and repetition are the whole thing. So it’s the performances that keep it fresh despite the reheated jokes, and that make the show into something funnier and indeed more human than interpretive readings like this one might suggest. There’s probably more art just in the physicality of On Cinema than in all its film-culture critique put together.

To wit my favorite thing the show’s ever done aside from the already recognized classic Trial is probably the 5th Annual On Cinema Oscar Special, which is full of engrossing drama and tangible pleasures: The video starts with a really good DKR set, is carried by Turkington’s exceptionally meticulous eyelid acting, then finally concludes with a fiery monologue that Heidecker performs with a startlingly emotive drunken clarity (“anybody that sits around watching movies and cares about who wins and loses is sick,” he says, ostensibly to needle Gregg but really to needle us, before slyly articulating the show’s central idea—“we all have a short time on this planet and if we spend it worrying about who wins an Oscar you might as well put a gun in your mouth”).

Not much in the 8th Annual reaches similar heights. Like many other Oscar Specials it concludes with a nearly fatal injury, yet for once the structure isn’t defined by a buildup of tension but rather by a procession of purposefully flat interstitials. So while prior entries have felt like comedy-melodramas squeezed into tubesite aesthetics, the 8th Annual and the HEI Network setup immediately reposition themselves as being something different and even more specific to the content era of public-facing web videos—and therefore even more reflective of just how inconsequential Hollywood movies have become during the same era.

Reflection is the ultimate quality of On Cinema, its critical implications cut so deep because its observations are so right on. And by now it mirrors basically the entire commercial filmmaking ecosystem: The cross-platform narrative gluttony reflects mass storytelling in the time of intellectual property; Tim’s obsession with pivoting away from movies reflects the industry’s consistent efforts to sublimate feature-length films into lowest common denominator content; Gregg’s pointlessly romanticized engagement with the form as a quasi-religious experience reflects one primary critical perspective of the current day (while Tim’s moral outrages reflect the other); the play-along fanbase reflects moviegoers’ apparently widespread desire to participate in and perhaps even control their favorite brands; the bland colors and chintzy post effects reflect the ever diminishing aesthetic expectations for digital cinema; and the recurring cycle of faux-corporate takeovers and rebranding campaigns reflect the unmatched capitalistic death drive of an industry that sells out to every caller from Dupont to Amazon to the Discovery Channel (and that last one even affected On Cinema directly, given AT&T probably cleared house at Adult Swim to prep numbers for the WarnerMedia sale).

And now with HEI Network, a genuine subscription-based streaming service that does for the show’s history what Disney+ does for Disney’s, On Cinema even reflects the distribution strategies controlling the scope and shape of contemporary American film—putting on a mocking imitation of the whole culture’s unceasing march towards synergistic consolidation under Netflix knock-offs. So as we enter this Discovery Channel era of Hollywood, which arrives in the midst of what’s surely the single worst stretch of commercial filmmaking in the history of the art form, the On Cinema project stands out as the only satire cruel and hateful enough to match the insipidness of the real thing. Probably the best joke ever told about the modern American cinema, On Cinema at the Cinema has claimed a rightful seat among its best comedies, and settled in as one of its major works.

The 8th Annual On Cinema Oscar Special is available on HEINetwork.tv as a “single ticket” for $12 or as a subscriber for $55/year.