“Now more than ever, family members and the wider community must have access to all public records when officers are investigated for misconduct—especially when they are cleared of wrongdoing.”

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court recently heard oral arguments in a case that will determine whether state and local governments can keep the public in the dark about information that originates from the federal government.

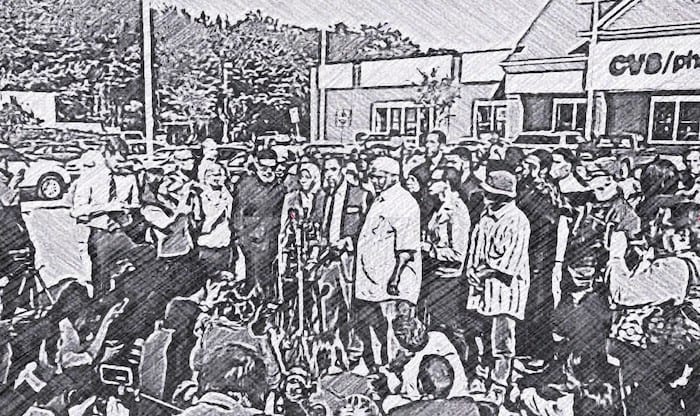

The case goes back to June 2015, when members of a Joint Terrorism Task Force comprised of Boston police officers and FBI agents killed 26-year-old Usaamah Rahim in a Roslindale parking lot. A year later, the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office—then headed by Dan Conley—said the killing was justified and declined to file criminal charges against any of the cops or feds.

According to the DA’s office, the JTTF members were trying to stop Rahim so they could question him about his involvement in a plot to kill police officers when he drew a knife and walked toward them, prompting one police officer and one FBI agent to open fire. (The DA’s office released a surveillance video of the shooting a week after it took place, but the camera was so far away that it didn’t show whether Rahim was holding a knife.) In his report on the shooting, Conley explained that his office relied in part on documents provided by the FBI.

The DA’s office released hundreds of pages of documents to Rahim’s family after concluding its investigation—but Rahimah Rahim, Usaamah’s mother, wanted to know more. On June 16, 2017, she filed a public records request with the DA’s office.

However, the DA refused to provide the FBI records, claiming that they were not covered by the Massachusetts public records law because they were on “loan” from the FBI with the condition that they not be disclosed to the public. The DA also claimed that the records were protected by the state law’s investigatory exemption, which allows government agencies to withhold many records that, if released, would hamper law-enforcement investigations.

On July 24, 2017, Rahimah Rahim filed a lawsuit against the DA’s office to force the disclosure of the records. On June 12, 2019, Suffolk Superior Court Justice Joseph F. Leighton Jr. ruled in favor of the DA’s office, accepting the idea that the documents were on loan from the FBI and therefore are not public records under state law. Leighton also ruled that the documents could be withheld under the investigatory exemption. Finally, Leighton held that the documents are covered by the federal Freedom of Information Act, so Rahimah Rahim would need to file a FOIA request with the FBI if she wanted a chance to read them. (In fact, Rahim did request the documents from the federal government the same day she requested them from the DA, but the feds also denied her request.)

Rahimah Rahim is being represented by Kate Cook and Tristan Colangelo—lawyers with the Boston firm Sugarman, Rogers, Barshak & Cohen—as well as several attorneys from the American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts. After the Superior Court ruling, the lawyers filed an appeal pointing out that the state’s public records law says that it applies to all records “made or received” by state and local government agencies, so the fact that the records were created by the FBI is not relevant.

The lawyers further argue that the DA’s office hasn’t met its “heavy burden” of explaining how the investigatory exemption applies to the FBI records. And even if the exemption applies, they argue, it might be possible to release the records with any sensitive information redacted.

The lawyers also argue that the Freedom of Information Act only applies to the federal government and does not bar state and local government agencies from releasing records even if those records originated with the feds.

While current Suffolk District Attorney Rachael Rollins, who took office in 2019, says she is committed to “an unparalleled level of transparency to … investigations [of fatal police shootings] with the hope of increasing the public’s trust in the District Attorney’s Office and the police,” her office has continued the fight to keep the FBI records secret.

Assistant District Attorney Donna Patalano, who is representing the DA’s office, argues that allowing state and local agencies to release documents that originated with the FBI would “chill” cooperation between local cops and feds. Patalano also writes that the records involve “national security,” so “[t]he District Attorney should not be put in the position of having to decide which records can be released, or what redactions are needed, in order to adequately protect the investigative techniques of the FBI or the lives and safety of its agents.”

Rahimah Rahim’s lawyers point out that the FBI could still allow local prosecutors to view sensitive documents without turning over copies, or it could make FBI agents available for interviews instead of providing documents. But, they write, “federal agencies should not operate under the illusion that they can indefinitely share documents with Massachusetts agencies without running the risk that those agencies will be required by state law to produce them to Massachusetts residents.”

Separate from the public records lawsuit, Rahimah Rahim filed a federal wrongful-death lawsuit against the federal government and JTTF members in 2018. In her SJC brief, Patalano accuses Rahimah Rahim of trying to “exploit [state law] to escape federal discovery practice in her federal lawsuit.” Rahimah Rahim’s lawyers call the accusation “dismaying.” They add, “If anyone is attempting an end-run around what the law plainly commands, it is not Ms. Rahim.” (Rahim is being represented by different lawyers in her federal lawsuit, which was filed months after the public records suit.)

The ACLU of Massachusetts notes on its website: “The Supreme Judicial Court [is] consider[ing] this case at a time when police are facing renewed scrutiny for fatal shootings and the use of excessive force, which disproportionately harms and kills Black people. Now more than ever, family members and the wider community must have access to all public records when officers are investigated for misconduct—especially when they are cleared of wrongdoing.”

However, the case has ramifications that extend beyond the behavior of law enforcement. In an emailed statement, Rahim family attorney Kate Cook explains: “The approach advanced by the District Attorney and United States in this case would significantly dilute access to public records and is wholly unworkable. It would make Massachusetts an outlier and effectively allow the federal government to decide whether and when Massachusetts residents may access records that their own government uses to carry out official acts in critical areas of public interest. And because state agencies and local governments routinely receive federal documents in almost every area of public policy, the threat to Massachusetts public records law cannot be overstated.”

The SJC oral arguments on Sept 11 were held virtually due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Cook argued on behalf of Rahimah Rahim while Donna Patalano represented the DA’s office. Additionally, Joshua Handell argued for the US Department of Justice, which submitted a friend-of-the-court brief in support of the DA’s position.

The late Chief Justice Ralph Gants, who had undergone surgery after experiencing a heart attack a few days prior, did not take part in the arguments; Gants died at age 65 on September 14. Justice Elspeth Cypher was recused. Video of the arguments is available at Suffolk University’s website.

During the arguments, Justice Frank Gaziano seemed to shoot down a core part of the DA’s case. Less than a minute into Patalano’s remarks, Gaziano interrupted her, saying, “[T]he plain language [of the law], really, is against you. … ‘Received’ means ‘come into possession of,’ and you didn’t create them, but you certainly came in possession of these documents.”

Later, Gaziano added: “Someone took a Bankers Box of documents and gave them to you. … So when you trip over them in the morning, wouldn’t you say you ‘received’ them?”

The quip drew laughs from both Patalano and Justice Scott Kafker.

“Your Honor, I would prefer not to trip over them in the morning,” Patalano answered.

Patalano and the DA’s press office did not respond to requests for comment, and Handell declined to comment.

Andrew Quemere has been making public records requests in Massachusetts for more than a decade. He writes The Mass. Dump Dispatch, a newsletter about public records. Subscribe to read about the latest developments in government transparency. Follow him on Twitter @andrewqmr.