We’re zooming—I’d barely heard of Zoom 10 days ago, and now I’m using it as a verb.

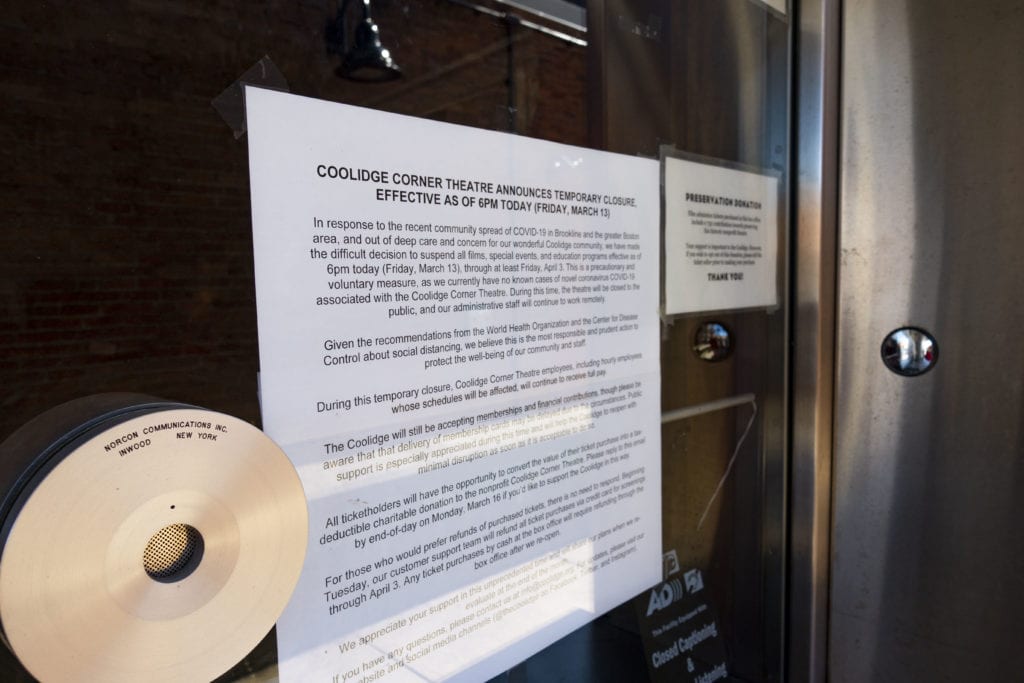

On Friday, March 13, the team at the Coolidge Corner Theatre announced the space’s temporary closure “through at least Friday, April 3” as a result of the ongoing pandemic. On March 23 and 24, I conducted interviews with various employees of the Coolidge about the situation, and found that a number of different phrases and memories recurred with great regularity—probably none more so than the word “strange.”

“It’s very strange,” said Andrew Thompson, director of operations at the theater. “I’ve been at the Coolidge for something like 22 or 23 years at this point, and we’ve only ever closed for blizzards, once or twice for an electrical outage, and 9/11, when I think we shut down for part of the day. That’s the only times I can remember being closed for anything, so I think this is the longest consecutive closure since we became a nonprofit.”

The Coolidge, which first began showing movies in 1933 and has operated as a nonprofit since 1989, is a four-screen first-run theater that on any given week is usually exhibiting a mixture of fiction and nonfiction films courtesy major studios and small boutique distributors alike. It also hosts a wide range of repertory screenings (usually on Monday nights, sometimes on Thursday nights, and occasionally at other timeslots as scheduling allows), which are themselves separated into a number of different subcategories (such as “Big Screen Classics” and “Science on Screen”). Beyond that, the Coolidge also hosts various other happenings on a weekly or semi-regular basis, including midnight shows every Friday and Saturday night (often repertory screenings from 35mm prints), live music events (albeit often with a film-specific angle), and various educational programs (and on that point, a disclosure: I’ve taught some educational seminars at the Coolidge during the past three years, and have been compensated with a percentage of the registration fees on those occasions).

On the night of its closure, for instance, the Coolidge was playing first-run films including First Cow (2020), Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019), and The Times of Bill Cunningham (2020), and had three different midnight programs scheduled including a double feature of Friday the 13th (1980) and Friday the 13th Part 2 (1981).

“When I got there on the 13th, it was not apparent that we were going to close that day,” recalled Mark Anastasio, director of special programming. “There was some discussion happening [to the effect of] this will be our last weekend before we close, and then it was actually we’re going to close on Saturday. Later the theater made the decision to just immediately close after the 4 o’clock round of shows on Friday afternoon, which thinking about it now was of course the only decision. Like, I had a costume planned—and something felt a little bit strange about parading on stage in a Jason costume, and then locking up the next morning and talking about how that might’ve been dangerous.”

This is the third in a series of DigBoston features regarding the status of local film institutions in the midst of our collectively shared crisis. Normally that information would just be included at the very bottom of the article, and italicized. But it seems pertinent to say it up here, too, because right now—as we wait for the wave of this pandemic to crest, and remain totally in the dark about what life will be like in Boston during the coming weeks, months, and years—the question of whether or not any given organization’s “status” currently holds even the slightest bit of importance seems to me an unanswered one.

But having considered what appear to be even the worst-case scenarios for how the next year or two may play out, I’ve reached the perhaps mistaken conclusion that there are probably three specific points about our film-art institutions that will remain of some importance no matter what goes down next. Those points, or questions, will guide these status reports going forward, or at least until I change my mind.

The first question, and certainly the least vital among them, is how these institutions are carrying on with their operations while temporarily shut down—what are they offering to the public? The second question, and certainly the most vital among them, is to what extent these institutions are working to keep their employees paid or more simply just afloat during these immensely difficult times—what are they doing for their workers? And finally the third question, caught somewhere between those other two, is whether these institutions are now in a state of financial precarity—what must they do to survive?

With this case, let’s answer that last question first: Basically everyone I spoke to at literally every level of the Coolidge Corner Theatre Foundation, ranging from floor staff to CEO and executive director Katherine Tallman, expressed that they are fully confident the Coolidge itself will reopen when large gatherings are no longer a threat to public safety.

“We’ve been an operating movie theater since 1933,” Anastasio told Vice for a story published earlier this month. “We became a nonprofit in 1989, when the theater was literally saved from demolition by people forming a human chain around the building. Keeping this place open will be a priority, even as the world falls down around us.”

His comments of course speak to the heartfelt dedication of the Coolidge’s staff and patrons. But frankly, they also speak to the fact that the Coolidge is better economically positioned than many of its brethren in the world of noncorporate movie theaters—or at least in some ways, if not all. To wit, the Vice article for which Anastasio offered comment was published with the following headline: “After Independent Movie Theaters Closed for COVID-19, Some May Never Reopen.”

“I fully expect us to reopen,” Anastasio told me during our conversation earlier this week, in some contrast. “I don’t really have a doubt about that. I know the financials are going to get difficult, but eventually the Coolidge is going to reopen, and I’m going to be there programming films. That is a fact. Maybe that’s hubris. But also a fact.”

“It took us a minute or two to get our bearings,” said Beth Gilligan, director of development and marketing, about working around the closure of the physical building. “But I feel like we’ve been working nonstop [since]. You’d think, they’re shut down, how busy could they be? But now we’re trying to figure out how we stay connected to our audiences.”

So far those efforts to “stay connected” have resulted in three distinct programs, all of which are obviously web-based. The first is the social media-specific “Staff Picks,” where Coolidge employees feature in videos recommending films currently available for home viewing. The second, hosted more specifically at Coolidge.org, is a “virtual education seminar”, which may soon become an ongoing series: Patrons will receive a prerecorded lecture regarding a specific film, then are meant to watch the film on home video or VOD, and finally join in on a Zoom call with the instructor for a post-film discussion (the first one is set for April 2, and will have Emerson College professor Andre Puca lecturing on Rear Window, 1954).

The third and probably most “newsworthy” of the team’s suddenly conceived online programs is the Coolidge Virtual Screening Room: In conjunction with a number of other, adjacent initiatives currently being rolled out by distributors including Kino Lorber, the website allows users to rent a movie in the manner of typical online VOD services—except the price is set around the same point as a theatrical screening, $12. Individual distributors handle the streaming end of the arrangement, and then split the proceeds with the Coolidge.

“Kino Lorber reached out to us to let us know they had this film, Bacarau (2020), which they were going to be releasing via their own streaming platform,” Anastasio explained. “But they were giving it a true theatrical window: Theaters can decide to open the film—quote-unquote—and date it, and have a link specifically tied to [their organization]. … That was exciting to us. And almost as soon as we received that email, we received dozens more from other small distributors offering films that we might not have even had the room to open [under typical circumstances] because our screens are always so full.”

To organize, test, and implement these programs into the Coolidge’s online system with essentially zero notice has required a great deal of effort from the staff, who at this point are working remotely. And that brings its own challenges: Among the office-level workers quoted so far in this story, most if not all are currently working from home with a spouse who’s also suddenly doing the same, and young children who are just as suddenly out of school or child care. “Right now, my wife is in the other room on a Zoom call reading stories to her students,” Anastasio mentions during our interview. “And we’re going to be celebrating my daughter’s second birthday under lockdown in a few days. So these are high-anxiety times.”

“We are doing Zoom calls, but I think everyone feels melancholy and that it’s not quite the same,” Gilligan said. The italicized quote at the very top of this article is hers. “We’re a very tight-knit bunch, and we’re a very collaborative staff, so I think everyone feels a sense of loss from not being around each other day in and day out. Because we do actually like each other—how weird is that? … And a few of us are parents who have young kids, and that’s challenging too, because you’re balancing trying to homeschool, or even just look after your kids, with doing your job.”

But each of the people interviewed also quite openly deferred any real concern they had about the Coolidge to the more specific matter of pay for the front-line employees—many of whom are on part-time schedules, and/or working on an hourly basis. And their worry is of course shared by the front-line employees themselves, or at least by the ones who gave notes on this story.

To be clear, payroll has gone out as usual ever since the closure: As was announced on the 13th, “[all] Coolidge Corner Theatre employees, including hourly employees whose schedules will be affected, will continue to receive full pay.” However, as Tallman explained to me during our interview, the matter of just how long that arrangement can be kept up is an open question. In fact the potential reopening date listed in that announcement, April 3, was even chosen for reasons specifically relating to worker pay. “We picked April 3 [to potentially reopen] because it was the end of the payroll,” she noted. “I said to my HR/finance guy, ‘What’s the easiest day to take us through?’ Well, let’s just take us through that payroll.”

My interview with Tallman was conducted on March 24, right before the passage of the federal stimulus bill that’s ostensibly meant to provide financial relief from the pandemic. At that point, she and other members of the Coolidge staff were awaiting the details of that bill in order to decide the best course for addressing worker pay beyond April 3.

“I’m committed to, and our board is committed to, supporting our staff as much as we can,” Tallman said. “And part of that will involve—I think we’re all still waiting for information on this federal package. And we’re [waiting for information] on benefits available via the Commonwealth—we hear about rent relief, mortgage relief, student loan relief, unemployment benefits, direct checks. … What I’m going to do is look across the board and see what options are available from an external support standpoint, then try and craft together a package that works optimally across the board—recognizing that we won’t be able to continue to fund the full freight [of costs] for an extended period of time, but also knowing that there will be some external resources available that can help with that, so that we can do the best we can do across our staff.”

On that point, Tallman provided an update via email this morning, March 30: “Now that the bill has been passed, Coolidge leadership is evaluating impact and will leverage options toward our goal to balance business viability and employee well-being.”

“It really comes down to the notion of are you paying 100%, right?,” Tallman elaborated later in our phone call. “I’ve been getting information and waiting for more information about exactly what’s going to be available with unemployment [via] the federal package. We don’t have all the pieces to the puzzle. We will continue to pay people. Will it be 100%? I don’t know. It’s not going to [continue to] be 100% for a long period of time, I can say that.”

Between the announcement of the temporary closure and my interview with Tallman on the 24th, the Coolidge had raised over $30,000 in donations, memberships, and gift card sales. Those funds—along with anything earned from the Virtual Cinema and other digital programs—will theoretically help to cover operating costs while the building is closed. But the question of how exactly to move forward grows increasingly present, especially as it becomes more and more obvious that the ban on public gatherings will last beyond April.

“I’m fielding calls from folks that had things scheduled with us in March and April, who are already looking to reschedule—but without knowing what we’re going to do with our own internal programming, I’m not really able to give anybody dates right now,” Anastasio mentioned. “We certainly hope to find dates to reschedule with folks that had plans with us, but we have to come up with what we’re doing with our own stuff [first]. Like I don’t know what this means for new releases that have backed up: Will March and April release dates be pushed into May and June, and does that push back anything else, or does it just mean we don’t open those films we had planned for March and April?”

Around this point I clarified to Anastasio that my concern with this interview was—for once!—not so much about the movies. “Well, shit, that’s my concern,” he responded. “My concern is when I can show people The Last Temptation of Christ (1988). It’s not going to be on Good Friday anymore, which I’m bummed about.”

As mentioned, the Coolidge officially remains closed through “at least April 3.” But Tallman, in line with comments made by other staff, stated pretty unequivocally that the closure will be extended significantly beyond that date. She also expects that the next public communication on the matter will announce that the theater will be closed “indefinitely.”

When asked to whom an institution like the Coolidge might look for guidance on when it actually will be safe to reopen, Tallman pointed toward the same forces that influenced the decision to shutter.

“As much as a lot of things are unclear, I do think things like [the] reopen date will become about as clear as it was to close,” she told me. “I mean, that became very clear—we need to close now. And we’ll be looking for the same things. … We’re going to look at infection rates and death rates. At this point, the government is taking that step, and there are more third parties imposing what can be done. So we won’t be making that decision in a vacuum.

“In terms of the immediate impact [of the pandemic], we’ve been really fortunate,” Tallman continued later. “The Coolidge has had so much support from donors and members over the past few years, and there’s been a lot of good film product, so we’ve been financially really sound. So we’ve had some ability to build cash reserves … [and] we knew we had enough to say, we’re closing and we’re paying everybody. And we got a lot of kudos for that—which is nice—but it’s also like, thank goodness we can do it, because not everybody can do that … [and] nobody can do that long term.”

The Coolidge’s status as a film institute with fairly stable financial backing and a relatively safe lease is mirrored (at wildly different scales, but still mirrored) by a number of other film institutions in the US—many of which are, like Tallman implies, facing down very difficult questions with regards to staffing and worker pay. One example would be the Film Society of Lincoln Center, which on March 27 announced that it had “taken the unprecedented step of furloughing or laying off approximately 50% of our full-time staff, as well as all of our part-time staff … to ensure that once we are on the other side of this unprecedented moment in global history that we will be able to start rebuilding and resume our mission to support the art and elevating the craft of cinema.”

Shortly after our conversation on the 24th, Tallman sent me an email to a fairly similar effect: “[It] occurred to me that you’re basically asking about balancing the needs of an institution [like the] Coolidge with individuals. And that’s what it’s all about,” she wrote. “We want and need to support individuals to the best of the organization’s ability to remain operationally healthy, and ensure there’s a place to ‘come home to.’”

This is the third in a series of DigBoston articles regarding the status of local film institutions and theaters during the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. The first entry reported on the Brattle Theatre, and the second entry reported on the Boston area’s corporate-owned multiplexes.