Stories of long separation from loved ones, along with forced isolation and inhumane treatment of pregnant women, are part of a broader story of abuse and neglect at MCI-Framingham

Three years ago, there was an unusual Saturday at MCI-Framingham, one of the oldest women’s prisons in the country. Food tables with hot dogs and burgers dotted the side yard by the utility barns, children ran around the compound, possibly playing with each other, or with their moms. There were kids’ games with prizes for the winners.

A party. Balloons hovered above the scene, within the iron fence perimeter. Deborah Goldfarb, a young licensed clinical social worker, stood to the side, under the summer sun, alert on her “crisis shift.”

The superintendent of the prison and several other prison officials were stationed in the grass, also watching. Nonetheless, the chance for incarcerated women at MCI-Framingham to spend quality time with their loved ones—albeit under intense scrutiny—was a rare opportunity. According to Deborah, it might have even been the first such event in decades under the Massachusetts Department of Correction (DOC).

Deborah’s job was to offer support in case the experience became too emotionally distressing for the women. But only about 10 women ended up being able to take part in the day.

“I remember there [was] definitely a handful of women who had hoped to participate but couldn’t,” Deborah explained.

Some families were unable to make the trip due to women being under disciplinary holds or being penalized in solitary confinement during the event. Others asked their loved ones not to visit. To enter the facility, families would be processed in the main building—family members above the age of four searched and patted down—then escorted out to the yard.

“They often would say, I don’t want my child to be searched,” Deborah said. “I don’t want my grandmother to be searched, or I don’t want my family to experience what I experienced [with] the correctional officers.”

Stories of long separation from loved ones, along with forced isolation and inhumane treatment of pregnant women, are part of a broader story of abuse and neglect at MCI-Framingham. As we documented in the first article in this series, the prison is currently the subject of two lawsuits brought by Lee Peck Unitt, a formerly incarcerated woman who is suing the Mass DOC on multiple counts of negligent health care, exposure to toxic chemicals, and harassment from prison guards and authorities.

Ms. Lee’s lawsuits are now proceeding in federal court. But the concerns they raise are just the tip of the iceberg. Formerly and currently incarcerated women told us that some of their deepest scars come from being separated from their children and families.

Catch the Hope

Zeno Williams was 20 years old and pregnant when she was arrested in 2002. She gave birth three months later while awaiting trial in custody.

“Seeing pregnant women in custody was one of the most horrific things,” Deborah said. “And it is fairly common.”

Catch the Hope is the name of the program in place at MCI-Framingham to help incarcerated women navigate giving birth in custody and planning for their child’s future. Pregnant women, who are required to wear light blue scrubs, are assigned a caseworker to coordinate with the Department of Children and Families and support them through their pregnancy.

Yet former DOC employees and formerly and currently incarcerated women said the initiative does little to ease the physical and mental toll of carrying a child behind bars.

“You are supposed to be able to speak to advocates who can help you overcome not being in a proper nursery, and your stress levels and things like that,” Zeno said. “[But] unless you were in distress, you were not allowed to speak with them.”

Zeno said that prison guards repeatedly told her not to go into labor while they were on shift. “They just don’t want to deal with it.”

Guards are also not trained to manage pregnancy behind bars. The 10-week mandatory training to become a corrections officer in Mass is largely paramilitary; job candidates learn the policies and procedures of the DOC—self-defense, firearm usage and security operations, and techniques for handcuffing and restraining people. Women’s health is an afterthought.

On one of her first nights on a clinician shift at MCI-Framingham, Jessica Pratas, a former prison clinician, responded to a “crisis call” from a woman who had just been separated from her newborn and was asking for a breast pump, a medical necessity for most women postpartum.

Jessica thought that since Framingham is a women’s prison it would have medical equipment for lactation.

“I was laughed out of the room,” she recalled. “It still makes me angry to this day.”

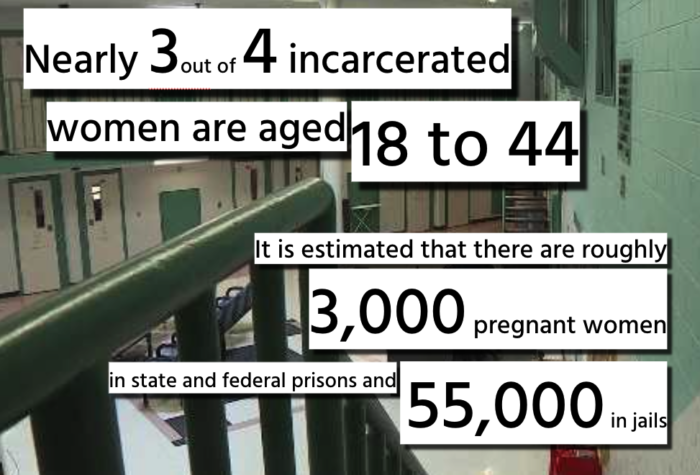

According to research on pregnancy and health care in prisons, nearly three quarters of incarcerated women are aged 18 to 44—prime childbearing years—and it is estimated that there are roughly 3,000 pregnant women in state and federal prisons and 55,000 in jails.

“Correctional health is so gendered,” said Donna Kohlin, a certified nurse and midwife at Baystate Midwifery and Women’s Health who works with incarcerated patients. “It’s all set up for men,” she explained, “and they sort of just extrapolate for women.”

For transgender women, there is no guarantee that they will be housed in a prison that matches their gender identity or given adqueate health care while incarcerated.

In 2019, Angelina Resto was the first transgender woman in Mass to sucessfully initiate her transfer from a men’s prison to a woman’s prison. Before being moved to MCI-Framingham, she was housed at MCI-Norfolk, where she was routinely sexually harassed by guards and other incarcerated people.

“Every time I would go to the shower, the corrections officers would let other inmates know so they could follow me in there,” she said. “I was told: You are not a woman, you are in a men’s prison.”

“Where is she going?”

When Zeno started having early contractions, her cellmates began yelling for help and banging on the door to their unit. She said a rookie male guard and a senior female guard drove her over an hour to UMass Memorial Medical Center in Worcester, the closest hospital contracted through the department to accept incarcerated patients who had gone into labor.

Zeno’s cervix was fully dilated by the time she finally reached the hospital floor.

“I barely got up on the floor [when] the doctors started scrambling and freaking out.”

Her left foot was shackled to the hospital bed during birth. After she gave birth, additional medical personnel rushed into the room when the baby appeared to not be breathing. During the commotion, the prison guard who had been waiting outside the door came into the room and shackled Zeno’s hands.

“When [the nurses] came over to give [my daughter] to me they saw that I was in cuffs,” Zeno said. “The nurse looked at the officer like, ‘Really? Where is she going?’”

In 2014, Massachusetts passed an “anti-shackling law” prohibiting handcuffing pregnant women during childbirth and postpartum, and requiring minimum standards of medical care and nutrition during pregnancy and postpartum recovery. However, according to a 2016 report released by the Prison Birth Project, the Department of Correction routinely violates this law, and there is no legislative or administrative oversight to ensure that pregnant women are not subject to inhumane treatment.

Zeno spent just two and a half days with her daughter before they were separated. Deborah said that women would often ask for a C-section instead of vaginal birth since the more invasive procedure meant a longer recovery time in the hospital and therefore an additional two to three days with their child.

Visitations at Framingham are limited and under the strict surveillance of corrections officers, and for many families, distance and travel costs are steep hurdles. Like most incarcerated women, Zeno experienced her childrens’ milestones and birthdays through phone calls, messages, and letters.

Solitary

Solitary

For women at MCI-Framingham, the trauma of being separated from their children and loved ones is often compounded by the prison’s policies of solitary confinement. Jamie Stykowski, a formerly incarcerated mother at the prison, experienced this firsthand.

A set of pale pink rooms located in the Smith Building east of the Framingham compound comprises the closed custody unit, or solitary confinement. Incarcerated women are confined to cells, usually about the size of a parking spot, for up to 22 hours a day.

Recalling her time in solitary, Jamie said, “There were unlimited Bibles.”

The story of Job, a wealthy man who had everything taken away from him, stood out to her most.

“I thought if he could get through it then I could get through it too.”

“There is no hearing at all before someone is placed in solitary confinement,” said Elizabeth Matos of Prisoners’ Legal Services. “People are placed in solitary pending review, so they can sit in solitary for months waiting for that to be adjudicated.”

The use of solitary confinement as a punishment is rooted in the early Quaker belief that isolating incarcerated people in small cells with minimal interaction and only a Bible would force introspection and rehabilitation. In practice, the use of solitary has been shown to cause significant, sometimes irreversible, psychological harm.

Moreover, “no touch torture,” particularly during the prison boom in the United States in the ’80s and ’90s, has been used disproportionately to segregate the mentally ill and as a racialized form of punishment for people of color.

Gov. Charlie Baker signed two criminal justice bills in 2018 that included restrictions on the use of solitary confinement for pregnant women and those with mental illness. But prison officials at Framingham have created new segregation units that sidestep these restrictions. New units—one is called the “secure adjustment unit,” the other the “secure treatment unit”—house incarcerated women, including those with mental illnesses, for up to 21 hours a day, one hour short of what is allowed by law.

The women we spoke to confirmed Framingham’s workarounds, saying their time in solitary was days, weeks, and even months longer than the state-mandated maximum.

When Jamie was sent to solitary confinement for the first time, it had been 20 months since she had seen her two children. She was on her way to her job in the cafeteria when she got into an argument with another woman.

An officer saw the interaction and wrote Jamie up for physical assault. The other woman involved in the argument signed a testimonial corroborating Jamie’s claim that no violence had occurred in the altercation, but Jamie was sent to solitary anyway.

The incident happened a few days before a Christmas party where Jamie was expecting to finally see her kids. Instead, with visitation revoked, she would be spending it in solitary.

Jamie was heartbroken. She said she could have gotten out of solitary if she signed a disciplinary report taking blame for the incident, but she was torn.

“If I signed it like the CO was asking me to [I could] get out of the hole, but also lose more good time,” Jamie said. “But if I didn’t, then I wouldn’t get to see my kids.”

Jamie said the prison chaplain, Rev. Lucy Marshall, came to Jamie’s cell door shortly before the party to tell her it had been postponed on account of a massive nor’easter about to hit Framingham.

“Sister Lucy said, He made it snow for you,” Jamie recalled. “I started crying because she said, [God] did that for you.”

However, as more time went by without any hope of coming out of solitary, Jamie ended up signing the disciplinary report anyway, relinquishing her right to a parole hearing and agreeing to loss of “good time” if it meant she could return to the general population.

After that, Jamie said, “I really focused on doing what I had to do to get out of there.”

Family preservation

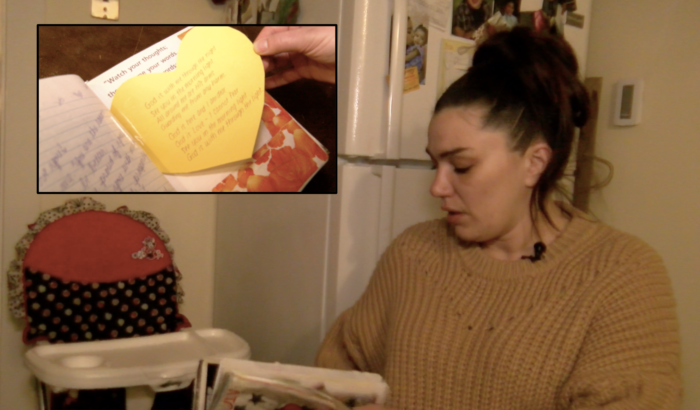

In her apartment, Jamie showed us a scrapbook all women receive as participants in Framingham’s Family Preservation Program—the prison’s attempt to maintain ties between incarcerated women and their children.

Decorated with magazine cutouts and colorful flowers in bright pink and yellow, the heavy hardback was coming apart at its spine. Audrey Hepburn replaced Lincoln on a simulated five-dollar bill pasted on one of the laminated pages and photos of both her children filled the rest of the book as she pointed out collected letters to her kids.

“This one is from a school project I helped [him] with,” she said, pointing to a pamphlet for a science experiment about an egg getting sucked into a glass bottle. A handwritten note next to it said, “This is cool. Do not PLAY with matches. Try this as a science experiment with an adult!”

As a consequence of parental incarceration, children are dealt the trauma associated with a caregiver’s physical absence and the stigma of having a parent in prison. Despite the circumstances, Jamie wanted to do everything she could to stay connected with her children during her sentence.

But Deborah says that despite the existence of programs such as the Family Preservation Program, MCI-Framingham offers little support for incarcerated mothers like Jamie.

“There wasn’t really anyone onsite there who was for [family preservation] that I think had the training or skill set to really support these women through the really hard task of trying to stay connected to your family, processing what losing custody of your children is, or trying to get custody of your children back,” Deborah said.

Deborah conducted three to four women’s group-therapy sessions every week ranging from substance use, grief, and depression to trauma and chronic pain with the assistance of an on-site nurse. She also saw a caseload of clients who attended individual therapy with her, as well as covering the psychiatric crisis shifts, where she was paged to different locations of the prison to assess those in mental crisis.

In the group-therapy sessions, women “would talk about stress at the institution like you would talk about stress at home,” Deborah said. “We talked about questions like, Where are their children? What is the relationship with the father who is taking care of them? Who will get custody?”

Despite Deborah’s efforts, and strong evidence tying stronger family connections to lower rates of recidivism, incarcerated women at Framingham struggle to stay connected to their loved ones.

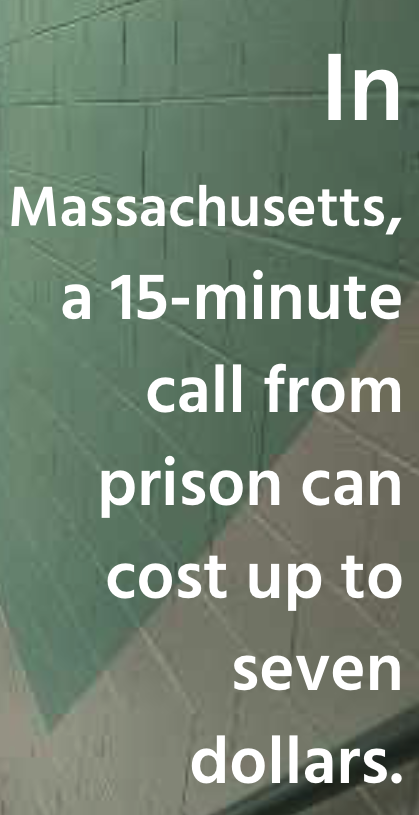

In Massachusetts, a 15-minute call from prison can cost up to seven dollars. Phone provider Securus, which processes more than 90% of the calls that come into and out of Bay State prisons and jails, estimates families with loved ones in prison pay up to $24.2 million a year for prepaid phone calls and fees.

Prisoner advocates and formerly incarcerated people are urging the state legislature to pass the No Cost Calls Bill, which would eliminate the cost of phone calls for incarcerated people and their families. Families for Justice as Healing, an advocacy group led by formerly incarcerated women based in Roxbury, surveyed 150 formerly incarcerated women from the most incarcerated neighborhoods in Mass—Roxbury, Dorchester, Mattapan, and Hyde Park—about the impact of incarceration, including the cost of phone calls. Nearly 45% of respondents spent more than $50 on phone calls per month, and one-fourth of the women spent more than $100.

By contrast, an average “unlimited” cell phone plan from a major network provider costs less than $100 a month.

For the past two decades, Zeno’s sister has called her twice a week to check in and make sure she has enough money in her canteen account for toiletries, food, and to receive phone calls. The retired EMT lives in Eastern Mass, not far from where their family settled after immigrating to the United States from a parish outside of Kingston, Jamaica.

“We have pretty much got to go by the rules that are set,” she said over the phone.

The cheapest bid

Before she worked at MCI-Framingham, Deborah attended Simmons College in a master of social work program and spent time interning at the Criminal Justice Institute at Harvard University, providing legal assistance to currently and formerly incarcerated people. When she decided to work at the prison, her colleagues were surprised, and Deborah remembers her classmates asking, You’re going to go work for the man? You’re going to work inside this institution?

You’re going to work in a place we need to abolish?

Although she shared mixed feelings about the next step in her career, the social worker said she believed at the time that the way to understand what was happening in institutions like Framingham was to work from within, and then, hopefully, have the experience and knowledge to advocate for reform.

Deborah’s hopes collided with the reality of life for women inside the prison. She quickly learned that the treatment she could offer differed from shift to shift, depending on which guards were on duty and who the shift captain was. If a guard believed in psychiatric care, they might allow Deborah to see her client, even if they were in solitary—if they didn’t, they would make it harder for her to reach them.

And according to Deborah’s former colleague Jessica, even if clinicians could meet with clients, it was nearly impossible to provide effective mental health care and rehabilitation inside the prison.

“We’re asking [incarcerated women] to dig deep in an environment where when they step out the door to our office, an officer is calling them the N-word, calling them the B-word, or calling them a cunt,” Jessica said.

Deborah cared for incarcerated women at MCI-Framingham, but her official employer was Wellpath, a health care company contracted under the DOC to provide care to incarcerated people. Wellpath is the largest for-profit health care provider to carceral facilities in the United States, holding contracts with over 500 federal and state prisons, county jails, and I.C.E detention centers spanning across 36 states.

Wellpath has also been named a defendant in over 1,300 federal lawsuits over the last decade. During the COVID-19 pandemic, incarcerated women reported that their health declined significantly due to lack of access to adequate health care and to being quarantined in their cells for up to 22 hours a day.

Deborah formed lasting bonds with the women she worked with, trying to work with them in whatever capacity she could. Yet she says she was routinely discouraged from speaking publicly on issues of mental health reform, in state house forums on incarceration, or in advocacy communities.

“There were multiple times when my supervisor [at Framingham] said things like, Remember who your client is. Your client is the Department of Correction,” she said.

A contract extends about four to five years before being renewed or terminated, then private companies can submit proposals for the following period.

“You know the bid that’s going to win is the cheapest bid,” she continued. “ [I]t’s like, Who can take care of this number of people for the cheapest amount of money?”

“Trauma informed”

Multiple recent articles by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism have covered the state’s plan to procure millions of dollars in funding to build a new, larger prison for women in Massachusetts, equipped with “trauma-informed” spaces and design.

In principle, the new design would mitigate some of the shortcomings in care and budget constraints Deborah struggled with in her time at MCI-Framingham. But Families for Justice as Healing and the National Council for Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls, both led by formerly incarcerated women in Massachusetts, have opposed the construction of the new prison. They say trauma-informed spaces cannot exist within a prison.

“The key component is dealing with the trauma of incarceration through mental health care, education, housing, and employment. We have been doing it their way for hundreds of years and it does not work,” said Leslie Creedle, a formerly incarcerated activist and the founder of a housing rights organization for formerly incarcerated people.

Instead of spending money on a new prison, Leslie said that with more funding, community-based organizations could do a much better job helping incarcerated and formerly incarcerated women. Currently, spending priorities in Mass skew strongly toward incarceration. The DOC budget grew at an annual rate of 18% between 2012 and 2017—more than the rate of growth for K-12 education aid budgets, and at twice the pace of local aid for housing, MBTA transportation, and MassHealth.

As time went on, Deborah would reduce her shifts at the prison and eventually go from her full-time position to per diem. When we spoke to her at the beginning of 2021, she hadn’t picked up a shift at the prison in nearly a year.

“I participated in an institution that has a really horrific history and has done really horrific things to people,” she said. “It was really hard to practice ethical social work inside the institution.”

This article was produced in collaboration with the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism as part of its prison reporting initiative.

Shelby is a graduate of Emerson College. She has been published in The Boston Globe, The New England Center for Investigative Reporting, and Spare Change News. She is passionate about covering prison health care and stories related to incarceration.

Twitter: @grebbin_shelby | Email: srgrebbin@gmail.com

Isha is a graduate of Emerson College, with a degree in Broadcast Journalism. She has interned with Boston-25, Channel 5 and the Belfer Center - all of which honed her attention in on long-form storytelling - both in TV news magazine format, as well as written narrative.

Twitter: @IMarathe | Email: isham7461@gmail.com