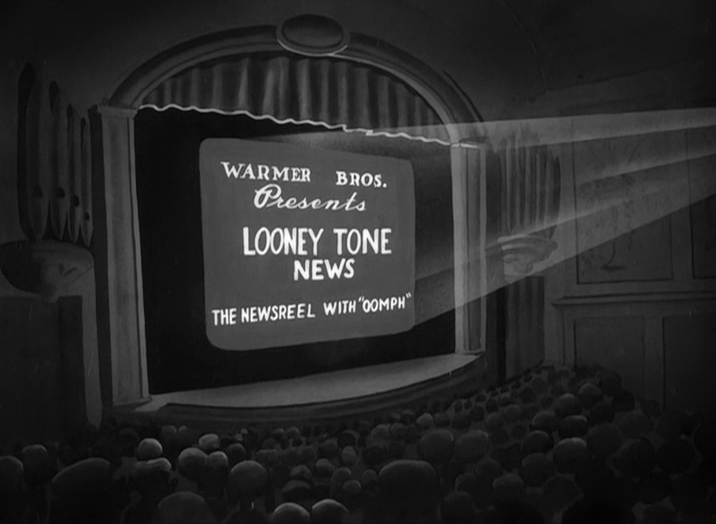

Presenting curated feature-length programs of Merrie Melodies and Looney Tunes shorts projected from their original 35mm exhibition format, the Brattle Theatre’s Bugs Bunny Film Festival is among the best annual events that Boston-area repertory cinema has to offer. Usually sticking to entries from the pre-60s golden days, the program has kept itself fresh over the years by presenting both canonical Looney shorts and lesser known entries, the hits to please the first-timers and the b-sides to satisfy the old heads. So while in this introductory passage I might be expected to provide some general commentary on the Looney Tunes, that seems to me against the purpose of Bugs Fest—which offers not only a rare opportunity to see the shorts in their original theatrical context, but also invites us compare them against one another. So accepting as we cultured Americans now do that Chuck Jones-era Looney Tunes sit near the peak of commercial film-art during its long-gone glory years of the mid-20th century, the next step is to undo our collective thinking about them as some amorphous collection of shorts indivisible from one another, and to start reconsidering them as the individual miniature-scaled film objects they really are. Hence this film-by-film report, arranged chronologically below, which accepts the Brattle’s potentially ironic “Festival” phrasing and finds that it holds up to heavy scrutiny—even outclassing most of its peers, just as the Tunes so often did to the features they preceded. —Jake Mulligan

Fast and Furry-ous

Directed by Charles M. Jones. US, 1949, 7 minutes.

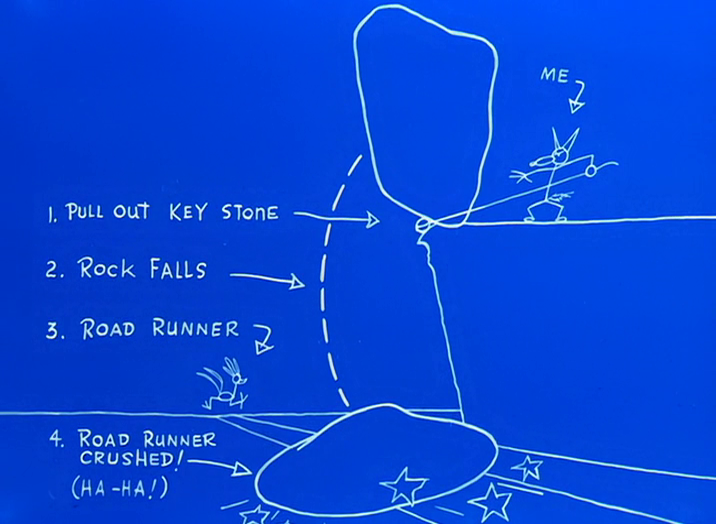

To my above point about judging Tunes against one another… to me you can’t really compare a Road Runner/Wile E. Coyote short to anything except another Road Runner/Wile E. Coyote short. Fast and Furry-ous is the first entry in the almost entirely Jones-directed series, and firmly establishes most of the standards that would remain through animator firings and company shutdowns all the way to the streaming revivals of today: A chase in an American southwest milieu, a pause for the fake Latin names, a few Acme contraption gags, some good business with a big rock, a painted landscape joke, obviously explosives, and finally a slightly underwhelming visual-punchline finale. So everything both prefab and profound about the series is already present here at the start—including the delightfully ramping speed of the animation, the plunking weight of the slapstick, the antagonistic perversity of the world’s gravitational logic, the childlike invention of Jones’ compositions (like the top-down view that sees only a pair of dots moving through flat two-dimensional paths), the whole Acme thing (that being an intensely American corporate presence flourishing even in a psychic mind-space inhabited by two mythic creatures), and of course the sincerely existential qualities of Coyote as a Sisyphean character forever chasing illusory success down the literal road (on the other hand, overarching series-long qualities not totally figured out yet include the background style, which is more textured and less vibrantly minimalist than in shorts to come, and the physical characterization of Wile E., which is slightly more straightforward and thus does less with facial expressions than do future entries, where reaction shots depicting the Coyote’s ever-dawning self-awareness of his own perpetual failure play like cinematic punctuation).

But that stuff applies to the whole series, the assignment here is Fast and Furry-ous. And when sorting out Road Runner cartoons, you do it by the specifics of the jokes, and the pace of the chaos. So, judging on pace… Fast and Furry-ous is by no means the fastest, nor the most surreal or creative—those honors might go to Hopalong Casualty (1960), or To Beep or Not to Beep (1963), both from the end of the Jones era, where the rapid joke structure and deadpan editing combine to deliver gags faster than you can laugh at them, and with more variations in length and rhythm than you find here. But on jokes… as mentioned, Fast and Furry-ous sets up a whole foundation for the next 20-odd shorts in the series to build on, a blueprint just like all of Wile E.’s. Thus Fast and Furry-ous sits alongside other films where essential American comedy performers truly established the architecture of their own dynamic, like Buster Keaton’s One Week (1920), the Marx Brothers in Animal Crackers (1930), and Jackass: the Movie (2002)—which features at least one scene, “Rocket Skates,” stolen directly from this short. [★★★★]—Jake Mulligan

Feed the Kitty

Directed by Charles M. Jones. US, 1952, 7 minutes.

Marc Anthony was a rambunctious oafish bulldog who appeared in many Looney Tunes shorts—and in Feed the Kitty, Jones had him meet his match. Not with another dog or even a similarly temperamental domesticated animal, but instead with an unspeakably adorable, big-eyed black and white kitten named Pussyfoot. While the duo would not have the longevity of other pairings, the moment in which you see in real time Marc Anthony go from a growling, snarling canine to dropping his defenses with Pussyfoot falling asleep on his back is one of the most precious moments in the history of the Looney Tunes. The tension in the rest of the short becomes about Marc Anthony trying to outsmart his owner, a housewife only seen from the waist down,by trying to protect Pussyfoot from being discarded as simply another thing he brought into his owner’s house. It is a wonderful subversion of the dog as caretaker, so completely open-hearted and sweet that it may give you a toothache. [★★★★★] —Caden Mark Gardner

Duck Dodgers in the 24½th Century

Directed by Charles M. Jones. US, 1953, 7 minutes.

Chuck Jones drew a line between the Looney Tunes archetypes, divided between ‘comic heroes’ and ‘comedians.’ Daffy Duck was the latter, the one who would often be the punchline or fail in pursuit of whatever situation the given Tunes formula beckoned. Nonetheless, Daffy’s relatability in those comic moments offered flexibility in his character, allowing the animators and writers to shapeshift him into different genres of storytelling. For instance the real-life USA vs. the USSR battle for world domination (the space race would only kick off a few years later) takes form with Daffy as space traveler Duck Dodgers—representing planet Earth, and getting into a dispute with Marvin the Martian of Mars over whether the mysterious Planet X can be claimed as a colony by either of them. The dispute escalates into a shootout and their fight reveals itself as a darkly comic sendup to the Cold War between superpowers, leading towards a uniquely discomforting ending where Daffy, with his partner Porky Pig by his side, becomes the perfect avatar of Cold Warrior America in all its hubris. [★★★★½] —Caden Mark Gardner

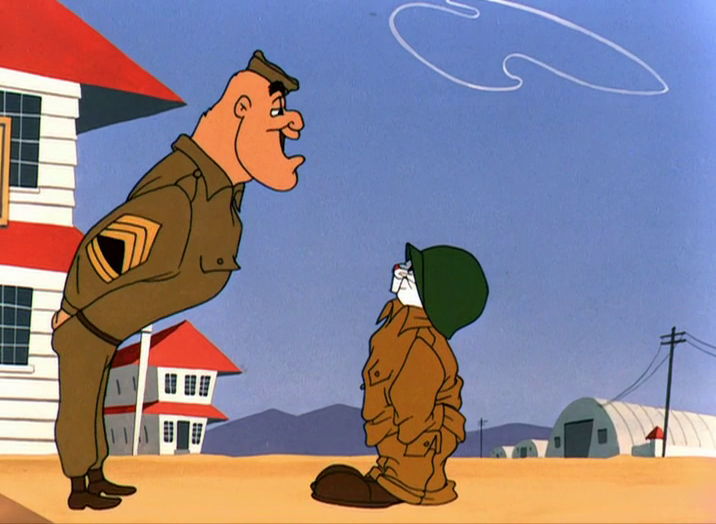

Forward March Hare

Directed by Charles M. Jones. US, 1953, 7 minutes.

It’s difficult to imagine Forward March Hare being made ten years earlier. As with most American media of the early-to-mid 40s, Looney Tunes/Merrie Melodies made their contribution to the war effort, producing jingoistic shorts like Daffy – The Commando (1943), The Fifth Column Mouse (1943), and Herr Meets Hare (1945). Even the most subversive of the bunch, 1945’s Draftee Duck, in which Daffy Duck attempts to dodge the draft, still essentially functions as propaganda, with the humor of the piece coming from Daffy’s exaggerated cowardice. Where Daffy, who typically acts as the butt of the joke in his toons, was an appropriate protagonist for the “Good War,” in which US citizens were to expected to bravely step up for humanity, Bugs Bunny is a much more appropriate protagonist for the Korean War, a proto-Vietnam proxy war that many found absurd and pointless in the present tense. Creating absurdity, of course, is Bugs’ specialty—he’s a comedic instigator a la Groucho Marx (Duck Soup, 1933) or Buster Keaton (The General, 1926), and Forward March Hare sees him bring his anarchic ways to basic training camp, causing various sorts of trouble for his supervising Sergeant. All the madness stems from a mix-up involving a “B. Bonny” having his draft letter delivered to “B. Bunny”—that it takes until the end of the short for anyone to realize the mistake hardly reflects well on the competence and organization of the US military. The most incendiary moment occurs when Bugs is awoken by a bugle, and angrily storms off to ostensibly murder whoever produced the noise, with offscreen audio suggesting he did the job. It’s revealed he merely destroyed a record player—but for a brief moment, we are led to believe Bugs is guilty of fragging! [★★★★] —Etan Weisfogel

What’s Opera, Doc?

Directed by Charles M. Jones. US, 1957, 7 minutes.

We live in an age where cartoons are, on the whole, pretty bad. They are either computer-generated plasticine monstrosities that induce psychological harm in children’s caregivers, or shows about the apparent trauma of horses getting MeToo’ed, or something else that by its end will make viewers long for the release of death. So, back to the good old days: Many people consider What’s Opera, Doc? to be the pinnacle of Chuck Jones’s Looney Tunes shorts, transplanting the familiar Bugs Bunny/Elmer Fudd antagonism into a condensed parody of Wagner operas. I can’t speak to any specifics of opera—a hick tendency I’ve worked hard to preserve—but the expressiveness of the animation is like a bolt of electricity. One of the first images is Siegfried né Elmer Fudd’s shadow, blue and ominous and coming up over a pale cliff streaked with faint wobbly lines that bear the mark of being painted by hand. And then a white streak of lightning, and the clouds parting again and again like a curtain to reveal shades of hyacinth purple and teal.

Like any Bugs Bunny cartoon, the plot is an excuse to have fun with dynamics: here it’s a chase (“kill the wabbit!”) , then a “will they or won’t they” routine. Bugs dons a breasty suit of armor and a wig with yellow braids and lures Elmer into a swoon, when Elmer realizes the deceit, he summons all the forces of nature to strike down Bugs. And what could be read as an icky moment of trans panic dissolves into dramatic remorse. “What have I done? I’ve killed the wabbit,” Fudd sings weepily as he carries off Bugs, their silhouettes black against streams of golden light. Talk about trauma: it’s silliness taken seriously, refusing to shy away from the bleak, beautiful, or stupid. But it doesn’t forsake comedy entirely, either—in the end, Bugs turns to us and implores: “Well, what did you expect from an opera? A happy ending?” [★★★★★] —Hannah Kinney-Kobre

Robin Hood Daffy

Directed by Charles M. Jones. US, 1958, 6 minutes.

Daffy Duck and Porky Pig are perhaps the most fascinating duo in Looney Tunes history, in that their pairing shifts Daffy more into a leadership role yet he nonetheless remains vulnerable to brutal slapstick follies due to his false sense of being not just the leader but also the hero. In this retelling of the Robin Hood story, Daffy has to prove to Porky Pig’s jolly friar that he is indeed the merry outlaw. In a metatextual way, Porky’s doubts are also a stand-in for the audience doubts in seeing Daffy take on this heroic role since our relationship to the character is largely seeing him slam into trees, be shot, or even disintegrated. Porky more than once breaks the fourth wall in his humored reaction to Daffy being much too ill-fitted to wear the green bycocket as the legendary bandit. Robin Hood Daffy ultimately shows Daffy perhaps at his most rational in ultimately accepting that he may well be best as the sidekick all along. [★★★★½] —Caden Mark Gardner

The Bugs Bunny Film Festival continues at the Brattle Theatre through Sunday, February 27. All shows on 35mm, see brattlefilm.org for showtimes. Program includes approximately ten shorts, lineup may change across days and showtimes.

Dig Staff means this article was a collaborative effort. Teamwork, as we like to call it.