Our first report on the 2020 New York Film Festival covered the Main Slate program. The following reviews cover films played in the Currents and Spotlight programs.

David Byrne’s American Utopia

Directed by Spike Lee. US, 2020, 105 minutes.

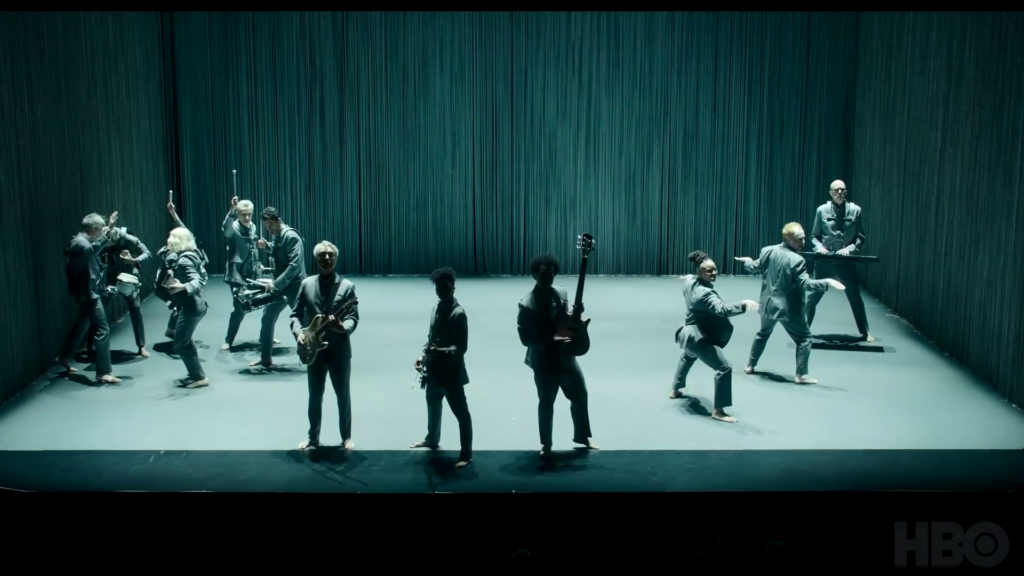

How do you make a concert documentary about David Byrne without falling into the shadows cast by Stop Making Sense (1984)? Spike Lee finds a way with American Utopia, which captures Byrne’s sparsely staged and invigoratingly choreographed Broadway performance of the same name from its 2019-2020 run at the Hudson Theatre. The show itself is an exuberant celebration of unity in the face of common struggle, with little nostalgia to be found. Byrne performs songs from his 2018 album American Utopia alongside newly arranged Talking Heads hits, as well as a booming cover of Janelle Monáe’s protest song “Hell You Talmbout.” Lee’s camera, so often bold and intrusive in his other work, closely follows the rhythm set by Byrne and his barefoot, gray-suited band members as they move across the stage. Although unexpected, Lee and Byrne are a rare creative match, and their collaboration is a joy to witness. [★★★★] —Cassidy Olsen

Now available with subscription on HBO Max.

Hopper/Welles

“Directed by Orson Welles.” US, 2020, 130 minutes.

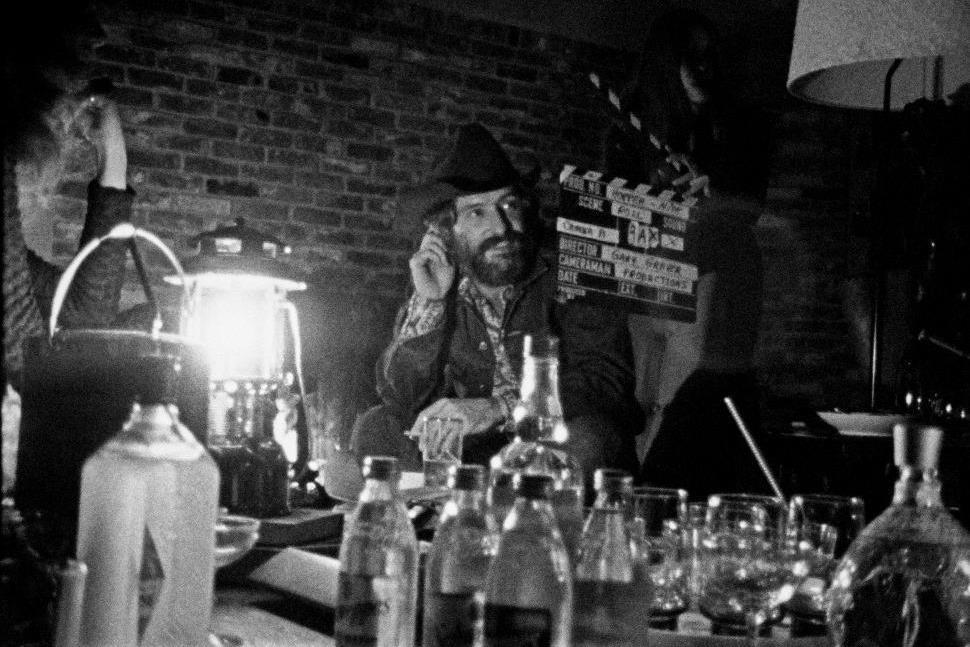

Orson Welles’ The Other Side of the Wind (2018), produced throughout the 70s then completed and released long after his death, features a very brief close-up of Dennis Hopper talking about how he’d like to get “John Wayne’s audience” into his movies. Aptly described by filmmaker Alex Ross Perry as “the first time that anything so stridently resembling raw footage has been packaged and assembled as a commercially available film,” Hopper/Welles is a slates-included portrait of Welles directing Hopper on the night he made that comment, shooting relatively simple black-and-white setups in a loose and improvisational manner devised specifically for Other Side. Knowing he’d utilize brief fragments at most, Welles stays off-camera and freely transitions between playing a role (the fictional studio-era director Jake Hannaford) and playing himself (complete with characteristically-ostentatious double-talk meant to trip Hopper up), pelting the younger star with conversational prompts that criss-cross between film criticism and more general art theory (from what do you think of Buñuel? to is a more personal film inherently of greater quality?), and then between circlejerkery and genuine sociopolitical inquiry (from how’s your new movie going? to what excuse could you have for not using your platform to advocate for violent revolution in America?), the whole time cannily angling to provoke one or two snappy lines worth keeping (and that John Wayne comment is indeed the one, a credit to the editing of Other Side’s final cut and a simultaneous discredit to the very conception of this companion piece).

It sinks because Welles interrogatory approach makes Hopper as reticent as any random celebrity at a junket, and when that’s combined with the new star’s obvious preconceptions of awe and even intimidation towards his offscreen elder, the result is a meandering conversation with no development of intimacy nor rhythm of exchange. In one of his moments as Hannaford, Welles knocks Antonioni’s contemporaneous films with a line that seems apt for reprinting here: “to transmit to an audience a feeling of juicelessness is a pretty dull thing.”

Hopper/Welles nonetheless serves adequately as a research document with dual roles. First, it exhibits how Welles shot the various interview sequences of Other Side in collaboration with his subjects and crewmembers including cinematographer Gary Graver. And second, it exhibits two-plus hours of halfway-unguarded rambling by Dennis Hopper at the peak of his cultural import in late 1970. But to present this lightly edited archival object as though it were intentionally produced film art is straight up fraudulent—and to list it as “a film by Orson Welles” is an insult to what the master filmmaker endeavored to accomplish with this footage in the first place. The producers and editors of this picture, who have carried themselves over from the postmortem Other Side production staff, obviously have their reasons for selling it that way. But in a just universe all jokers playing along with the charade would have to justify it to the man himself. [★★] —Jake Mulligan

The Inheritance

Written and directed by Ephraim Asili. US, 2020, 100 minutes.

The debut feature from Asili, The Inheritance is at once a joyous tribute to radical Black arts and literature, and a mournful reflection on how alternative ways of living and being are so often stamped out by oppressive forces. With a bold color scheme straight out of Godard’s La Chinoise (1967), Asili’s film is largely a dramedy of manners depicting a group of young Black radicals who embark on a project of intentional and politically informed living in West Philadelphia. But within that narrative shell, there’s a tragic, nonfiction core; around halfway through its runtime, The Inheritance temporarily mutates into a documentary about MOVE, the Philadelphia-based anarcho-primitivist group who were ruthlessly bombed by police in 1985. Though Asili’s touch is often light and the film’s manner fairly comic, the references to MOVE offer a sharp dose of reality: Almost any attempt by Black people in this country to live autonomously is met with swift, violent repression. [★★★½] —Nadine Smith

Next online screening via the Indie Memphis Film Festival beginning today.

Her Socialist Smile

Directed by John Gianvito. US, 2020, 93 minutes.

After a series of globetrotting films savaging the foibles of American imperialism in the modern world, hometown documentary poet and Emerson professor John Gianvito returns to a New England-based subject for Her Socialist Smile, a bewitchingly empathetic portrait of Helen Keller’s underdiscussed if not outright obscured legacy of radical activism. Given that the film is built scrupulously around text and speech, with forays into archival imagery and impressionistic footage acting as a buttress to lengthy blocks of onscreen text rather than vice versa, one might uncharitably point to Gianvito’s academic background and call Her Socialist Smile little more than a dry history lesson (this is a film in which a change in font color counts as something of a third-act twist). But Her Socialist Smile’s minimalist approach to biography and history is elevated by a deep-seated identification with its pioneering subject, a woman whose profound insight into economic and social inequality was fostered not so much in spite of her disabilities but because of them. Gianvito adopts the monkish poise and sobriety of Keller’s engagement with the world around her, using roving shallow focus shots of leaves, branches, and flowers to approximate the zest for nature that galvanized her thinking. And that thinking, in turn, might just galvanize us: As Keller, in one of the many eloquent letters preserved here, skewers Woodrow Wilson for his fealty to capitalist interests and grieves over the illusion of democratic citizen power, it’s impossible not to be reminded of the morass in which we now find ourselves. [★★★★] —Carson Lund

Next online screening via the Indie Memphis Film Festival beginning October 22.

Dig Staff means this article was a collaborative effort. Teamwork, as we like to call it.