With smoking confined to the couch-and-television set more than ever before, it seemed natural that for the cannabis issue of DigBoston I would ask our writers to provide notes on their favorite stoner movies. But that prompted the question—what’s a stoner movie?

On the one hand, there is the stoner film, a genuine subgenre: movies that are specifically about characters who smoke a lot of weed—usually two male buddies—and the shit they get into while they do. Other identifying hallmarks of the subgenre include bumbling Keystone cop villains, set-pieces focused on body fluids, and a sort of leery stoner-boner sexual energy that objectifies most female characters on behalf of the presumed audience.

It’s a tradition fairly bereft of high points. For every Fritz the Cat (1972), Friday (1995), or Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle (2004), there’s 50 iterations each of films like, well, The Nine Lives of Fritz the Cat (1974), Next Friday (2000), or A Very Harold & Kumar 3-D Christmas (2011). Plus if we’re being completely blunt, that first group doesn’t quite measure up to the highest grade either—the Bakshi film is the best of them, but even he’d go on to better work. And let’s not even get started talking about how most definitions of the stoner film subgenre loop in problem-film exploitation movies like Reefer Madness (1936), which do have qualities of note but at the same time have as much to do with movies like Up in Smoke (1978) as those old car-crash scare films you used to see in driver’s ed have to do with Fast Five (2011).

Then finally on the other hand there’s what we might call for the purposes of this article, “stoner movies”: films that don’t necessarily involve the consumption of cannabis, but at least seem to fit the mood when played in a smoked-up room.

So in this feature, you’ll find examples to meet every possible interpretation of the phrase: films about characters who smoke weed, films to watch while you’re smoking yourself, films made by artists who were definitely smoking while they made them, and even films that were entered into the canon by historically significant stoners.

Because though we may decline to define the “stoner movie”, we can at least contribute some titles to the list. —Jake Mulligan

The Saragossa Manuscript

Directed by Wojciech Jerzy Has. Poland, 1965, 182 minutes.

Imbibed substances and altered states have long been linked to The Saragossa Manuscript, which adapts the text left behind by the legendary Polish Count Jan Potecki when, in 1815, he came to believe himself a werewolf and committed suicide with a silver bullet. The film maintains the novel’s Arabian Nights-inspired tales-within-tales structure, which blooms outward especially in the post-intermission half of Has’ full-length cut. Unfortunately such nuances were lost on initial US audiences of the film, who in the late ’60s and early ’70s saw a version cut down to about two hours flat. That’s perhaps no surprise given that, in an interview published by Film Quarterly in 2000, the owners of the famed Elgin Theater recall that Saragossa’s then-US distributor was a Chicagoland butcher who owned just a couple of prints (also relevant to our subject, in the very next line they recall a guy who once told them my friend put himself through school selling drugs during the all-night shows [in the] back of the theater).

Even in that cut-down form, this early cult film attracted the attention of figures including Luis Buñuel and Jerry Garcia—who, considering Manuscript his favorite movie, commissioned Bay Area curator Edith Kramer to locate a print of the original three-hour edit. As she told SFGate in 1999, the only print she could find arrived the day after Garcia died: And even that one turned out to be incomplete, a two-and-a-half-hour version originally made for distribution across Europe. At this point enter Francis Ford Coppola (another smoker, as described below) and Martin Scorsese, who secured the creation of a fresh negative based on the last remaining copy of the original film—a personal 35mm print owned by the director himself. That was the version released to theaters in the late 1990s, on DVD shortly thereafter, for retrospective screenings including at the Brattle Theatre in 2014 and the Harvard Film Archive in 2015, and eventually on Blu-ray in Europe. And so now we have the complete iteration of this masterpiece, with some very storied and very stoned forebears to thank for it. —Jake Mulligan

Available on Blu-ray.

Kid Blue

Directed by James Frawley. US, 1973, 100 minutes.

As the title song goes: “Kid Blue, what’s wrong with you?” Even among the rough crowd of 1970s revisionist westerns, James Frawley’s Kid Blue is the most jubilantly anachronistic of them all—not to mention, deeply under the influence. Dennis Hopper plays the eponymous role, who is to the standard Old West bandit what Inherent Vice’s Doc Sportello is to a standard private gumshoe: a bewildered, burnt-out boyish-wonder mirror image—a stoned reflection of their respective straight archetypes (post-Easy Rider, 1969, Hopper had essentially parlayed himself into being the avatar of branded counterculture—the Jim Beam ads he starred in with fellow actor/director John Huston had the tagline, “Generation gap?”—but it was a well-earned rep, as his performance here illustrates). The film was written by gonzo journalist Bud Shrake, who frames the Old West as a place of reinvention where the past is nonetheless inescapable, especially for his title character. Kid Blue has fallen through the cracks despite both an immense cast (not just Hopper but also Peter Boyle, Janice Rule, Warren Oates, and Ben Johnson) and being classified within the most celebrated of American film genres. Perhaps it doesn’t get the respect it’s due because it’s so openly the stoned l’enfant terrible iteration of the western. A shame, since it’s by far the most unique of its era. —Caden Mark Gardner

Available on VOD and DVD.

Score

Directed by Radley Metzger. US/Yugoslavia, 1974, 91 minutes.

Somewhere in a fantastical European riviera is the city of Leisure, where liberated couple Jack and Elvira’s married bliss includes betting on which one can seduce the most people. The squarer, the straighter, the better, and innocent Betsy and Eddie are looking perfect for a night of groovy culture shocks. It’s not as simple as wife-swapping; oh no, you don’t give a young couple poppers and nun and cowboy outfits without any intention of queer revelry: If Elvira can’t bed Betsy by midnight, then Eddie becomes fair game for Jack.

Aside from some truly iconic ’70s reefer smokin’, this golden age softcore isn’t much concerned with the inhalable ambrosia, but it certainly won’t get in the way of Metzger’s sex-utopian vision of shag carpeted swinging. Truth be told, this intoxicated writer fell for its “sex comedy” genre tag and was surprised—but not disappointed—when, after 45 minutes of Samantha Jones jokes, Score became a remarkably staged, gleefully performed, and gender-damning porno of considerable artfulness. Come for the jokes, stay for the cum (and the cinematography). And the knowledge that the off-Broadway play on which it is based (!) starred a young Sylvester Stallone (!!) as a telephone repairman (!!!)? That’s just the icing on the ******. —Juan A. Ramirez

Edited version available on Amazon Video. Uncensored version available on Blu-ray/DVD.

Cheech and Chong’s Next Movie

Co-written and directed by Tommy Chong. US, 1980, 94 minutes.

Up in Smoke is a pretty great comedy that bears the stamp of record producer/director Lou Adler as much as Cheech and Chong themselves, especially once it reaches its conclusion—a blatant advertisement for the pair’s albums and live concerts. And films three-through-six in the C. and C. canon, from Nice Dreams (1981) through The Corsican Brothers (1986), provide diminishing comic returns alongside their diminishing onscreen marijuana use—byproducts of the boys growing apart, grasping for more salable personas, and losing their spark in the process. But Next Movie, their second feature and the first of four to be directed by Chong himself, is in the context of this particular Goldilocks scenario the one that’s just right—it composes the stoner pair through screen-space (and space, literally) with even more of a 70s Hollywood vibe than their actual 70s Hollywood movie did. Stumbling through master-shot long takes on deceptively elaborate locations and sets, they hilariously underplay their gags with the help of the grainy (hazy) photography and muddy sound design. Intricately detailed yet quite easily watched outta the corner of your eye while rolling something up, Cheech and Chong’s Next Movie is the one they should be remembered for. —Jake Mulligan

Available on Blu-ray/DVD and VOD.

O.C. and Stiggs

Directed by Robert Altman. US, 1987, 109 minutes.

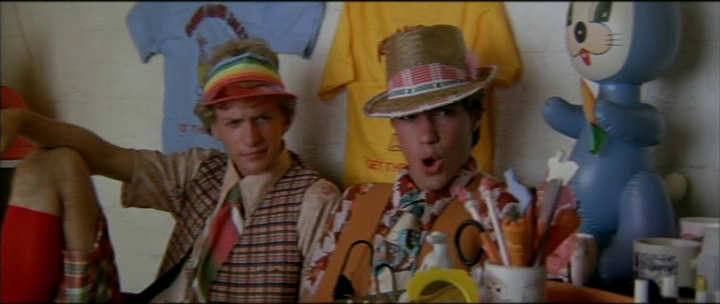

Although joints light up in the margins and cutaways of countless Robert Altman movies, the quintessential American smoker-director never made a genuine stoner film. Probably the closest examples are the handful of absurd comedies he directed in the 70s and 80s—all with ludicrously expansive production design worthy of his wide frames and their narcotized drifts: First the movie that made his name, MASH (1970), then Brewster McCloud (1971), HealtH (1980), Popeye (1980), and finally O.C. and Stiggs, which adapts a one-off National Lampoon issue depicting the prank-laden summer vacation of two racist, misogynistic, unrepentantly sociopathic white Arizonian teenagers. Shot in 1983, the film got shelved by horrified executives until it popped up as a b-side in a Dennis Hopper retrospective at the Film Forum in 1988, and even since then has gotten little play save for a few impassioned tributes including a shout-out from America’s most blunted auteur, Harmony Korine, whose own film Trash Humpers (2009) suggests what a more direct adaptation of the original Lampoon issue might’ve looked like.

Altman does keep the outlines of the original story; that O.C. and Stiggs (Daniell Jenkins and Neil Barry) are jokerfied teen menaces with a predilection for offensive language, that they live in a Reagan-era suburban hell near Phoenix, and that they’re engaged in a rather violent prank-war with the insurance-selling Schwaub family (led here by a dad played by Paul Dooley). But he softens the characterizations, framing the pair up as gleefully reckless anti-authoritarians more than as genuine forces of evil—in other words, as teenaged knockoffs of MASH’s Hawkeye Pierce and Trapper John, a comparison that Altman made himself on set. Building on the style he established in that film and those other aforementioned comedies, O.C. and Stiggs lets all its jokes slowly enter Altman’s glacial pans without much of the traditional setup/payoff film-grammar, instead placing emphasis on the layers upon layers of production design: Genuinely-insane made-for-the-film vehicles, egregious costuming (see above), and chintzy department-store set dressings, all laid out in flattened wide frames perfect for the groggy-eyed viewer that can’t quite achieve focus anyway. In a definitive report on the production published by Apology Magazine in 2013, producer Allan Nichols remembered that “I could see Bob misinterpreting National Lampoon for MAD Magazine back then,” and the resulting film suggests that Altman never disabused himself of that misinterpretation, albeit for the better—like Brewster McCloud before it O.C. and Stiggs has a distinct Alfred E. Neuman-energy, with Altman’s stoned-out glancing-view cinema ideally attuned for a comedy where half the gags happen in the background.

Actually each of the film’s overstuffed settings brings its own iteration of specifically-American stupidity: The Schwab house a pastel-colored palace of rinky-dink lawn ornaments and home decor, putting even the suburban hellscapes of John Waters to shame; and O.C.’s home a dilapidated shack overseen by his ex-cop grandfather (Ray Walston), who tells grisly crime stories that only add to the film’s dense tapestry of western disreputability. Meanwhile, Dennis Hopper and Melvin Van Peebles appear in a grow-house and behind a dumpster—as his character from stoner film masterpiece Apocalypse Now (1979) and as the self-dubbed “Wino Bob”, respectively—finally orienting this whole proudly-meaningless picaresque as a blackpilled howl emerging from the void of a counterculture that’s been bought, resold, and now finally placed into cameo parts of a National Lampoon movie. A catalog of detritus both consumer and corporeal, “combin[ing] frightening noise with the ugliness of poverty”, O.C. and Stiggs can now be seen for what it is, one of the truest American films of the 1980s. —Jake Mulligan

Currently unavailable by legal means—check your library for the out-of-print DVD.

Teen Apocalypse Trilogy: Totally Fucked Up, The Doom Generation, and Nowhere

All films written, co-produced, and directed by Gregg Araki. US, 1993/95/97.

Gregg Araki makes films that play tag among the notions of what stiff-lipped parents think smoking weed does to teenage disaffection and what existentially agitated teens might say is actually the case—that it’s the world that’s stoned. After making his debut with a series of low-budget films in the late 80s and early 90s, it slyly makes sense that Araki would make three films collectively dubbed the Teen Apocalypse Trilogy. The unofficial series, which helped launch the careers of Rose McGowan, Margaret Cho, Guillermo Diaz, James Duval, and others, follows disaffected, often stoned teens thrust into world-bending scenarios, like an alien invasion into a lover’s body (Nowhere), or the accidental manslaughter of a store clerk (The Doom Generation). Moral danger confronts the viewer as a major plot point; however, the chaos is often chalked up to a world beyond teenage control, and last-minute foolery is usually all it takes to save the day—or destroy it—reminding us that at the end it’s all a joke (if nothing else). At once paranoid and easy, Araki’s trilogy doesn’t just feature teens smoking pot at parties—it tries to portray, with visual dexterity, what reality would look like if reality were a stoned kid under the bleachers (in the ’90s, of course). —unsigned

Currently unavailable by legal means—check your library for the out-of-print DVDs.

Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge

Co-written and directed by Aditya Chopra. India, 1995, 189 minutes.

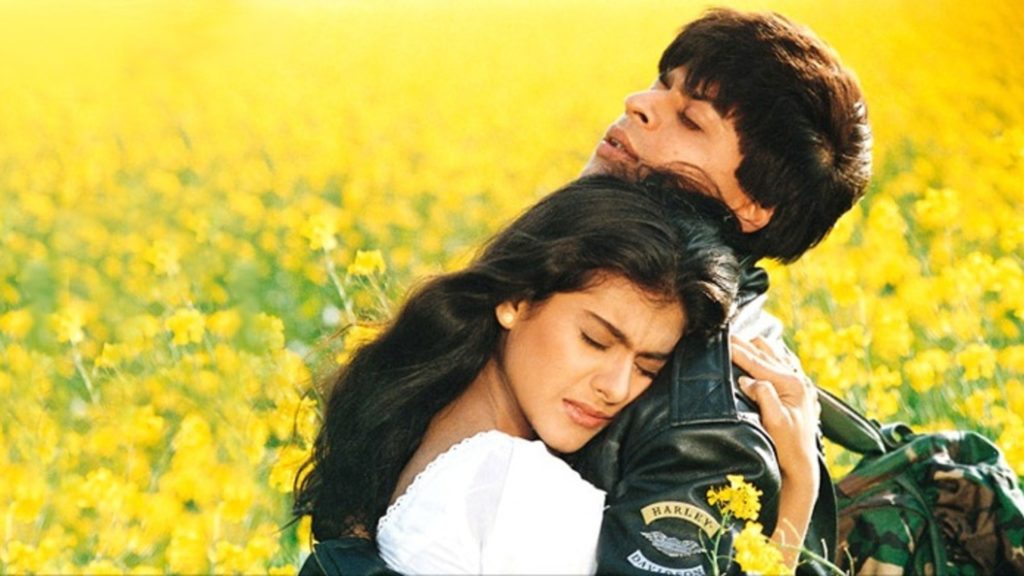

Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (often abbreviated to DDLG), is maybe one of the most popular Bollywood films of all time. And it is—to get to the point—a fucking blast to watch under the influence. Two luminously star-crossed lovers, Simran (Kajol) and Raj (Shah Rukh Khan)—both Indians raised in London—tour Europe, fall in love, and return to their ancestral homeland in order to face and then thwart Simran’s arranged marriage. This is a movie steeped in unforbidden pleasures, the kind that might under other circumstances read as typical or cliched but here are instead raised to the highest possible art: Happy families! Fields of yellow flowers! Shah Rukh Khan’s malleable, caricature-handsome face! Heterosexual romance! Backup dancers dressed in berets and knee-high boots! The Alps! But the deepest pleasure of them all is that of the gesture: the tenderness with which Shah Rukh Khan dips and dives as he dances or the equal parts warmth and fury of Kajol’s glances.

The hyperfocus that weed can induce is almost a superpower in that it is able to suddenly—if momentarily—make formal qualities into narrative ones; I once watched an episode of Nathan for You (2013-17) while [redacted] that convinced me the plot of the show was really about what people were doing with their hands. The way someone moves suddenly becomes a plot of its own, every stray movement of a hand or arch of a back as tense as a shootout. The density of detail that characterizes a Bollywood blowout, when viewed through a haze, becomes suddenly clarified. In a state of fantasy so hysterical that it’s easy to dismiss it or enjoy it only through a fine mesh of irony, weed is a marvelous equalizer. It returns us, against the stupidity of our “better judgment,” to pleasure. —Hannah Kinney-Kobre

Available with subscription on Amazon Prime and on some VOD platforms.

Wonder Boys

Directed by Curtis Hanson. US, 2000, 111 minutes.

As I see it, any film in which a pro- or antagonist is committed to cannabis is as much a weed movie as any dumb buddy bong flick. So while the image of Ice Cube in Higher Learning (1995) sorting a tray full of grass with a pick in his puff is a classic, and Outside Providence (1999) is a personal fave that I think many would label as burnable media, my instinct to follow the character before the story leads me away from that pack and toward one estimable Grady Tripp.

The spliff-twisting prof played by Michael Douglas in director Curtis Hanson’s take on Michael Chabon’s novel of the same name, Wonder Boys, is the fictional author of the brilliantly titled The Arsonist’s Daughter and flames Mary Jane throughout—typically while driving. Douglas’s portrayal of a burnout scribe is spot on right down to the stained and disorderly corduroys. If you’re not familiar, just imagine Lester Burnham from American Beauty (1999), but rather than spurring from some kind of a midlife crisis, his philandering hot-boxing recklessness has been raging since grad school.

Onstage last year at the Coolidge Corner Theatre following a special screening of Wonder Boys, Douglas said that it’s “one of [his] favorite movies,” notwithstanding it being “a bomb.” Thankfully, many critics and viewers in the years since have finally recognized not just its greatness, but also its green streak. That’s gotta count for something; if any group can push a film into the cult realm, it’s people who like getting stoned and streaming things.

Oh, and speaking of Michael Douglas, if there was ever a script that could have used a few joints, it’s Falling Down (1993). Fucking movie would have ended with the Whammy Burger scene. —Chris Faraone

Available on VOD.

Smiley Face

Directed by Gregg Araki. US, 2007, 84 minutes.

Lady stoners have gotten the short end of the cinematic stick. But fear not—there’s at least one canonical text. When Gregg Araki turned his attention away from twinks post-New Queer Cinema, he arguably made his best and certainly funniest film to date with Smiley Face: An episodic comedy following a female stoner, played by Anna Faris in a tour de force of performing increasingly altered states. The film is a day in the life of Jane (Faris), specifically the day when she eats an entire batch of pot cupcakes. But despite the obvious setup, what separates Smiley Face from most of its stoner-genre brethren is just how playful it gets—the plot and style of it feels closer to a Looney Tunes/Chuck Jones/Frank Tashlin sensibility than Cheech and Chong (it’s no surprise that Smiley Face screenwriter Dylan Haggerty would later work on one of the best Looney Tunes successors, Adventure Time). And despite Jane’s stoner-meets-dumb-blonde persona, there’s a lightly subversive edge: While super high, she gives a rowdy and galvanizing worker-solidarity speech at a meatpacking factory—but only in her own head, as revealed by a follow-up scene showing what really happened—a fake-out gag only recently topped by DiCaprio’s Belfort’s attempts to drive on quaaludes in The Wolf of Wall Street (2013). —Caden Mark Gardner

Available free on Tubi or with subscription on Amazon Prime.

Youth Without Youth

Written, produced, and directed by Francis Ford Coppola. France/Germany/Italy/Romania/US, 2007, 125 minutes.

Bogged down, beset, and bankrupted by Hollywood for decades, Francis Ford Coppola liberated himself to make exactly the kinds of movies he wanted to make by becoming a lifestyle brand first. Daddy Coppola got his money right by expanding into wine, then pasta and resorts, and now, yes, even marijuana: The Family Coppola® entered the cannabis market in 2019 with its “Grower’s Series,” which packaged three grams of flower together in a faux wine bottle for $99. At that time, a representative for Coppola stated that weed “had been integral to his creative process”—which is probably unsurprising considering the shell-shocked haze of Apocalypse Now or the sumptuous palette of Dracula (1992). But there’s maybe no movie by Coppola more thoroughly stoned than Youth Without Youth, his much-misunderstood return to filmmaking after a decade-long hiatus. Tim Roth plays an aging Romanian academic who has spent his life searching for the original, primitive human language. In a sort of cosmic Benjamin Button scenario, he is struck by lightning and regains his youth, along with an expanded mind and something close to superpowers. It’s a dazzling labyrinth of a film that mutates between genres and languages, as much a living biological organism as a work of art—and it benefits from an enhanced perspective, whether that’s a cloud of smoke or simply an open mind. —Nadine Smith (host, podcast Hotbox the Cinema)

Available on VOD and Blu-ray/DVD.

Inherent Vice

Written for the screen and directed by Paul Thomas Anderson. US, 2014, 139 minutes.

What’s funny about Inherent Vice (besides, you know, all of it) is that it’s actually less of a stoner film than the novel it’s based on. Thomas Pynchon’s Inherent Vice, published in 2009, goes even further with the Cheech and Chong in Paperback vibe, conjuring up a faux-Black Lizard-lineage detective story where stoner-sleuth Doc Sportello (played in the film by Joaquin Phoenix) searches for his ex-old lady Shasta Fay Hepworth (played in the film by Katherine Waterston) but gets derailed at every turn by vibrant hijinks like for example a guy named Denis (pronounced like penis) running around with a pizza on his head. Anderson is faithful to the source, as the saying goes, but more in terms of narrative and dialogue than in terms of comic tone: Downplaying much of the original text’s ostensibly movie-friendly physical comedy in favor of O.C. and Stiggs-worthy design elements and weirdly deadpan framing choices, the humor of Anderson’s Inherent Vice creeps up with a zonked dryness—one that the director would seize upon and parch even further in his next feature, Phantom Thread (2017), a comedy so dry that it’s desiccated (and another great film).

Being a tale about a joint-ripping detective unraveling a mystery that in one way or another revolves around the end of the American counterculture, Inherent Vice obviously passes the stoner film qualification test on story alone. But the comedy of it, somehow upfront and offkey simultaneously, pushes it even further into that realm. In fact the faux-lazy long takes—actually some of the most exacting compositions in the director’s body of work—now remind me of nothing so much as the similarly master shot-heavy Cheech and Chong’s Next Movie. And I’d say the best jokes in this movie play out kind of like how the best jokes play out in that one: They’re hard cuts to outré costumes and befuddled faces, or the mess of a home in the background of a shot, or the way a stray foot or joint lingers in the foreground, or the doped-out stumble of an extra (or a lead!) as they pass their way through a frame. Like Eyes Wide Shut (1999) did for the erotic thriller, Inherent Vice seems to put a capstone on the stoner film subgenre—while also elevating it, with the greatest of sincerity, to the level of high art. —Jake Mulligan

Available on Blu-ray/DVD and VOD.

The Beach Bum

Written and directed by Harmony Korine. US, 2019, 96 minutes.

The Beach Bum might be Harmony Korine’s first whole-hearted attempt at a genre film: the stoner comedy. Sure, you could call Spring Breakers (2012) a crime drama—it looked close enough to trap a bunch of very disappointed moviegoers—but The Beach Bum ticks box after box on our collective mental list of something to watch when you’re high. Matthew McConaughey doing a bit? Check. Jonah Hill as a sidekick? Check. Snoop Dogg introducing us to his purple grow operation and a magical, cataract-ridden pilot? Check and check.

But Korine doesn’t let The Beach Bum pander to anyone; it’s outrageously funny yet resists Hollywood formula at every turn. Moondog, McConaughey’s sun-addled Florida poet without a care in the world, doesn’t learn anything on his bizarre adventures. He drinks, he smokes, he pushes people into harbors, he keeps living. Korine’s cyclical editing pushes the momentum, staging conversations across multiple settings. Half the jokes feel ad-libbed. This shaggy dog story, like Moondog himself, is playfully defiant of convention.

The soundtrack is equal parts yacht rock, Jimmy Buffett (who does not actually make yacht rock), and the Cure, creating a beautiful auditory wave of chill-out lows and fuck-yeah highs. Also, Isla Fisher smokes a bong while getting eaten out. It’s a movie for whooping and hollering at alongside your closest friends and stoner allies—and an insidious way to convince them to watch Spring Breakers with you later. —Cassidy Olsen

Available on VOD and Blu-ray/DVD.

Dig Staff means this article was a collaborative effort. Teamwork, as we like to call it.