Jackass Forever

Directed by Jeff Tremaine. US, 2022, 96 minutes.

Now playing at most local multiplexes.

The name Jackass Forever suggests many possible readings, let’s start with the easy ones. First, it’s wordplay—this being the fourth mainline feature in the Jackass series, thus, four-ever. Second, it’s tribute—cast member Ryan Dunn died in 2011, and the film concludes with a “Forever” title card sending love to his memory. And third, it’s a statement of principles, because in recent years there have been spin-offs like Jackass Presents: Bad Grandpa (2014), and branded specials like the moderately entertaining Jackass Shark Week (2021), but nothing closely resembling the OG show or the first three movies, meaning this latest theatrical entry returns the cast and crew to the iconic gonzo Jackass format for the first time in more than a decade—making the moniker like a marketing-concocted promise to never go completely astray with side projects, and to respect the nature of the original article Forever.

Given my standard critical proclivities I must also consider at least one less generous reading of the film’s title, which is that it represents the desire of the groups who control Jackass, the ViacomCBS-owned Paramount Pictures and the Johnny Knoxville/Jeff Tremaine/Spike Jonze-owned Dickhouse Productions, to keep this gravy train running Forever. Given that Hollywood studios are so preoccupied with refreshing profits on pre-existing creative properties that said efforts have defined the American media culture of the last 10 or 15 years, my point that Dickhouse and Paramount want Jackass to keep going likely goes without stating. Yet it’s still vital to state it, because the aesthetic standards and corporate expectations of each Jackass feature’s respective film-historical moment is the primary factor granting the movies their own individual distinctions, and this new one is no exception.

First let’s clarify that Jackass Forever is the same kind of movie as its predecessors, despite any contemporary inflections. Like the others it presents roughly 90 minutes of pranks, stunts, gross-outs, physical challenges, hidden camera sequences, observed backstage interactions, and slapstick comic setups, ranging in length from seconds to minutes, some introduced with title cards and others played as interstitials, and many elevated to the level of real art by the cast’s well-practiced and highly sophisticated execution of (a) anticipatory buildup, (b) physical pay-offs, (c) verbal punchlines, (d) expressive characterization and ensemble dynamics via unscripted comments and physical gestures, and (e) great selling to illustrate the violence and injuries, these performance techniques all combining to consistently achieve each level of critic James Agee’s “four main grades of laugh—the titter, the yowl, the belly-laugh and the boffo.”

Scene for scene, minute for minute, joke for joke, Forever is among the most perversely creative and motherfucking funny American movies of the past couple decades, which also just means it lives up to the Jackass standard. To wit, it presents a small handful of sequences that immediately enter the series’ canon, like another multi-part “Cup Test,” a brilliantly succinct recreation of the old Road Runner painted landscape gag, and the latest in Knoxville’s long-running series of bull stunts. At press time, I’d put this first theatrical cut of Jackass Forever on a tier with Jackass 3D (2010) and slightly below Jackass: The Movie (2002) and Jackass Number Two (2006), and only because the latter pair rest comfortably on the highest level of art that American commercial movies can plausibly achieve.

So with caveats now made about the relatively consistent quality of the new film compared to prior entries… What’s most interesting at the moment of Jackass Forever’s premiere is not what’s good about it, but instead what’s different about it. Because there will be a day when Forever is fairly reduced to Jackass 2022, just as 3D can now be reduced to Jackass 2010. So the question becomes, what about them makes that so? What makes it Jackass 2022 besides all the N95 masks?

For instance Jackass: The Movie was produced during the early digital-video era of Hollywood, a period the show itself helped to define alongside other reality television and films like The Blair Witch Project (1999), and therefore it’s the last of the series to even moderately resemble the purposefully crude photography of the original MTV episodes. Jackass Number Two came out deep into the era of record-setting DVD profits for comedy films, and thus benefited from higher resources increasing the production value and scale of the stunts—while also inaugurating a new series tradition of deliberately overshooting footage to allow for home video-bound half-sequels like Jackass 2.5 (2007). Jackass 3D, produced and distributed from start-to-finish in less than 10 months after the release of Avatar (2009), announces its own film-historical trend right there with its title. Finally Jackass Forever emerges into an era of Hollywood that’s defined by spun-off serialized franchises, so-called cinematic universes, and highly sentimentalized remake-sequel hybrids, each designed to convert audiences’ nostalgia for older commercial products into subservient fandom towards the next generation of stars.

And despite seeming like a renegade antidote to the prescribed venom of those global-scale sci-fi blockbusters and superhero movie bummers, there’s at least a few spots where Jackass Forever exhibits comparable symptoms, albeit not the full sickness.

One symptom is the inclination to self-mythologize. Even moreso than the reverently backward-looking Jackass 3D, Jackass Forever is quick to communicate the implicit value of its performers’ tenure—opening with an atypically punchline-less comment from Steve-O about the years that have passed by, and cutting to flashback clips alongside redone stunts with greater regularity than before (the original lineup is maintained less the late Dunn and his CKY compatriot Bam Margera—so now it’s Knoxville, Steve-O, Jason “Wee Man” Acuña, Dave England, Preston Lacy, “Danger” Ehren McGhehey, and Chris Pontius). Restaging the stunts themselves is standard, since Jackass redid scenes from Big Brother magazine and CKY videos as early as S01E01. And the juxtaposed images of young early-00s bodies and their old present selves are potent too, given that aging has always been a primary thematic concern of the series. Yet there’s also this false sense of importance coded into the flashbacks—some of which have been shifted to black-and-white from the original color, as if to say that 2000 might as well be the 1920s. Forever seems to be selling the idea of Jackass as an eternal constant of American life, right in line with wider Hollywood efforts to solidify long-term growth potential for each individual project, and to be increasingly blatant about structuring commercial films like the vested stocks they really are.

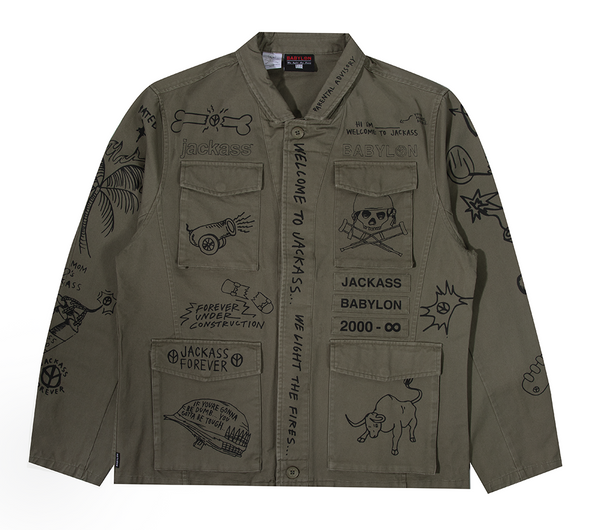

That’s not to say Jackass is any more or less corporate than it was on day one, but just that it does exist within the Hollywood system, and thus follows its generational whims. I’m reminded of the recent Babylon x Jackass merch drop that included a M65 jacket faux-personalized with the phrase “2000-∞,” which depending how you read it is either a lovely sentiment or a business plan adopted directly from Disney.

Speaking more towards ∞, new cast members have also been added for Jackass Forever, like it’s a new season of Saturday Night Live (1975-) or something: The opening credits introduce Odd Future member Jasper Dolphin, late-2010s MTV regular Zach Holmes, Knoxville’s Action Point (2018) co-star Eric Manaka, obscure social media personality Sean “Poopies” McInerney, and comedian Rachel Wolfson to the official lineup. As with most contemporary Hollywood sequels that pay sentimental tribute to prior entries, the new cast is purportedly filled with childhood fans of the original material (there’s shots of performers comparing Jackass tattoos—more self-mythologizing), as well as purposefully diverse when compared to the prior list. To be more specific, whereas previously the Jackass roster featured only men and appeared to be comprised almost entirely of white people, now there’s a few black people and one woman too—which I report in such blunt terms only because those added roles are yet another quality of Jackass 2022 that lines up almost exactly with larger tendencies in contemporary Hollywood products, which so often trumpet small or even tokenistic advances for “diversity in casting” like they were radical political stances worth rallying around (and perhaps the Jackass crew hasn’t done much trumpeting, but they’re definitely in the same marching band).

As a result of these myriad relatively minor developments there are ways in which Jackass Forever functions not too differently from, say, recent Sony-made Spider-Man films Into the Spider-Verse (2018) and No Way Home (2021). These movies and countless others released by Hollywood in the last few years all run the same playbook… Knowingly creating links between the stars we’re ostensibly nostalgic for and the younger performers expected to carry the series beyond them, while also diversifying the onscreen talent pool in line with contemporaneous expectations, and simultaneously throwing every formal technique imaginable towards mythologizing prior entries as having been seminal moments in modern American culture. Some of these changes are positive on their own, but it’s worth remembering the real end goal for this set of artistic tendencies, which collectively took hold on the culture via superhero movies and large-scale remakes but now crosses over to films like Jackass on a level that I suspect is less superficial than subconscious—the point is to goose the given series forward to a place where it might exist beyond the influence of its original creators and contributing artists, for the greater benefit of shareholders both public and private. At the conclusion of Forever, in lieu of a stinger advertising the next entry, a filmgoer may wonder if the younger cast will launch a new version of the television series, or if they’ll continue to cross over with the old crew in features, or if they’ll branch out to establish more spin-offs and monetized side-projects like Bad Grandpa and Jackass Shark Week, or, at least, that’s what Dickhouse and Paramount want you to be thinking.

One thing I was thinking was that I wish there was a place at theaters for movies that aren’t features. Jackass is oft compared to silent-era comedy and specifically Buster Keaton because of the complex setups x lowbrow slapstick concept, but given my obsession with the specifics of distribution I’m personally more amenable to comparisons between Jackass and old Looney Tunes cartoons, or between Jackass and the sound-era Three Stooges theatrical short films—basically, comparisons between Jackass and the kind of stuff a moviegoing audience of the 30s or 40s might’ve seen in between programmers from Columbia Pictures or Warner Bros. I think I was thinking this because Jackass was always too class for the internet, and too raunchy for television, and too physically risky for features to be produced on the standard biannual or triannual schedule, but for eight or 10 or 12 or even 20 minutes each, to be screened before the occasional R-rated picture from Paramount… doesn’t that seem just right, like a dick joke delivered at the perfect time? Yet now I’m daydreaming new ways to someday give Jackass more of my money, doing exactly what Hollywood wants me to do, being a mark for the movies like anybody else. [★★★★]